This week's news that President Obama will end the 54-year-old American trade embargo against Cuba and restore diplomatic relations marks a major change in Cuban-American relations. ABAA members have many fascinating items that chart the ebb and flow of American involvement in Cuba over the twentieth century, and a search for items relating to Cuba on our website can be a fascinating exercise. Members have documents signed by Fulgencio Batista, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevera, along with other participants on both sides of Cuban history. Letter signed by all Moncada prisoners, including Fidel Castro (1953) Archive of Documents relating to the Bay of Pigs invasion... Documents relating to Hemingway's time living in Cuba are enlightening, both for students of the great author's career and those interested in Cuban politics. Ernest Hemingway draft and corrected letters to Fulgencio Batista (part of a larger archive of Cuban interest) Members also have various editions of the classic Blue Guide to Cuba, a popular guide book to the pre-revolutionary island. Perhaps we'll see a new generation of those classic Cuban guide books once the travel restrictions are lifted. [more Cuba: Items of Historical Interest]

On Collecting Books

At Pazzo Books, the shop that I kept for years in the outer neighborhoods of Boston, MA and now run out of a two-story in-law addition in my home, I've learned that old books are funny things. Often you catch them looking at you sideways, across a room, and it occurs to you to wonder what they've seen; where they've been; and what odd parade of owners they've survived. Typically you can only imagine, but once in a very long while a book wanders through with enough information stored in it, in bookplates, inscriptions, and ephemera, that you can piece together a narrative. Évrard Titon du Tillet, great patron of the arts, son of Maximilien Titon de Villegenon, secretary to Louis XIV and alleged Scotsman, plotted to build a vast sculpture garden to celebrate the great writers, dramatists, artists, and musicians of France. Originally planned around a bronze statue, a model and description of which was executed in 1718, the project soon incorporated dozens of artists, growing to resemble a great folly (a penchant for which ran in the family; the Titon family mansion was called La Folie Titon). The budget swelled to 2 million livres and Tillet was forced to abandon the project. Instead he turned his Parnassus into a book, Le Parnasse François, the first and largest installment of which appeared in 1732. Additions, often occasioned as artists died or gave up their craft, appeared in 1743, 1755 and 1760. This particular copy has the 1732 edition bound together with the 1743, and a... [more History Between the Pages]

'Deckle edges' are the rough, untrimmed edges of a sheet of handmade paper (the deckle, from the German Deckel, 'little cover,' being the thin wooden frame around the mould on which the pulp is placed). John Carter's ABC for Book Collectors notes that deckle edges are 'much prized by collectors, especially in books before the age of edition-binding in cloth, as tangible evidence that the leaves are uncut; for the deckle edge normally would be—and indeed was meant to be—trimmed off by the binder.' I should note here the distinction made by booksellers between the terms 'uncut' (or 'untrimmed'), which means the deckle edges have not been cut off, and 'unopened,' which is used to describe a book where the conjoined leaves of a gathering have not been cut open with a paper knife, in preparation for reading. Carter has a separate entry for 'deckle-fetishism,' which he defines as 'the over-zealous, undiscriminating (and often very expensive) passion for uncut edges in books which were intended to have their edges cut.' Collectors (and, naturally, booksellers) have always particularly prized copies with ample margins. Size often does matter when comparing copies of books from the hand-press period. Deckle-fetishism seems to be a peculiarly Anglo-American affliction. I know French and Italian collectors, for example, who would prefer a book to be in a contemporary binding, rather than having it uncut in the original printed wrappers. Each to their own. Of course, one could argue ... [more Deckle-Fetishism]

ABAA member and children's book expert Chris Loker, owner of San Francisco's Children's Book Gallery, has curated a new exhibition opening on December 10th at the Grolier Club in New York City. One Hundred Books Famous in Children's Literature showcases seminal books that have proven to be landmarks in children's publishing. The exhibition includes such beloved books as Robinson Crusoe, Grimm's Fairy Tales, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Tom Sawyer, Treasure Island, Peter Rabbit, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Peter Pan, Winnie-the-Pooh, Charlotte's Web, The Cat in the Hat, Where the Wild Things Are, and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. Curator and children's book authority Chris Loker has secured loans from major institutions throughout North America for this exhibition, including the American Antiquarian Society, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, Cotsen Children's Library, Princeton University, the Houghton Library, Harvard University, and The Morgan Library & Museum -- as well as numerous distinguished private collections. A page from Orbis Sensualium Pictus The oldest book in the exhibition, Orbis Pictus, published in Nuremberg in 1658, is a bilingual schoolbook in simple encyclopedic form for young students of Latin (the text is in both Latin and German.) Used for two centuries throughout Europe, it is an early effort at integrating text and pictures. The most-recent book is one of the first 300 copies of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter and t... [more Exhibition: 100 Famous Children’s Books]

On September 25, 1789, as the momentous first Federal Congress drew to its close in New York, the new national capital, Representative Elias Boudinot introduced a resolution calling on President Washington to “recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer . . . acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.” A leading opponent of the resolution, Thomas Tudor Tucker, asked, “Why should the president direct the people to do what, perhaps, they have no mind to do?” The skeptical congressman noted that the people “may not be inclined to return thanks for a constitution until they have experienced that it promotes their safety and happiness.” He also argued that it was a religious matter and thus proscribed to the new government. Regardless, the House passed the resolution — one of their last pieces of business before completing the proposed Bill of Rights. The Senate concurred three days later, and a delegation was sent to meet the president. Washington, who had in fact anticipated the question in a letter to James Madison a month earlier, readily agreed. On October 3, President Washington signed the document offered here, America's first Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation. Washington employed the exact language of the resolution to begin his proclamation, though he went furth... [more The First Thanksgiving Proclamation]

The Vietnam War was America's most influential event from 1950 to 2000. The conflict, more than any other contemporary occurrence, changed American society, foreign policy, politics and the military. Although I grew up after the war ended, I have always had an interest in the conflict and how it affected the United States. I wrote my college thesis on the use of Old Glory before, during, and after the Vietnam War era. A rare Ho Chi Minh signed photograph, taken at a Soviet airport. Based on my curiosity, I have, for the past fifteen years, been collecting all aspects of the Vietnam War – posters, letters home written by soldiers and prominent people, photographs, books, flags, buttons, medals, pamphlets, and much more. There are now thousands of items in my archive and growing daily. A few highlights of my collection include: A rare Ho Chi Minh signed photograph A John Kerry letter inviting a Congressman to the ceremony where he threw his war medals A first edition of the Port Huron Statement put out by the Students For A Democratic Society A letter by Senator Pat McNamara on the very day President Johnson signed by Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, defending the bill A signed photograph of the legendary Marine sniper Carlos Hathcock who scored 93 kills in Vietnam A 1970 Bill Clinton letter discussing his draft number A book signed by many of last Marines rescued from the Saigon Embassy rooftop A President Nixon letter to Henry Cabot Lodge, the former ambassador to South Vietnam, ... [more Collecting Vietnam War Memorabilia]

The recent posts by Peter Stern, Rusty Mott, and Joyce Kosofsky made me wish I was in Boston last weekend for the book fair, but circumstances conspired against it this year. However, in a spirit of Bostonian collegiality, I thought I'd write about something I have noticed in the past here in Europe: the false Boston imprint. Last year, Mitch Fraas at the University of Pennsylvania made a study of fictitious American imprints before the year 1800. By his count, there were 173 European books which purported to have been published in America, but weren't. The vast majority of those (136) took Philadelphia as their imprint, but Boston comes second, with 19. These 'not Boston' books are quite scarce, but you do see them from time to time. Here are a couple of examples. This is a translation of the spurious Memoirs of an unfortunate Queen, originally published in 1776 by the London bookseller, John Bew. The public bought up two editions within the year, and Bew also brought out one in French. The 'unfortunate queen' was Caroline Matilda (1751–1775), the youngest sister of George III who was married off to her cousin, Christian VII of Denmark, when she was only 15. It was not a happy marriage. Christian was a mentally unstable philanderer who claimed it was 'unfashionable to love one's wife', and Caroline eventually drifted into an affair with the royal physician Johan Struensee, a rising star at the Danish court who effectively ruled the country for ten months as Christian's men... [more Not Boston]

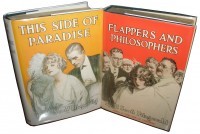

Although created almost a century ago, the art and writing of the Roaring 20's still captivates us today. Writer F. Scott Fitzgerald left behind some of the most iconic stories of this fascinating time period. The radical social change he wrote about was also evident in the art that adorned his dust jackets, as the artists who designed them had an uncanny ability to capture the zeitgeist of the era. Art imitated life, and Fitzgerald and his publishers knew how to captivate the attention of a younger generation, the ones who were behind all this change, like never before. Fitzgerald's first three dust jackets were designed by artist William E. Hill. Hill had made a name for himself illustrating for Puck magazine and the Sunday New York Tribune. His ability to depict everyday people in natural settings was well-known, so when Scribner's editor Maxwell Perkins needed to choose an artist for Fitzgerald's upcoming publications, he looked to this established artist. This Side of Paradise (1920) depicts an elegantly dressed young man and woman, portraying all the decadence and extravagance of the era. The cover art for Flappers and Philosophers (1920) features an illustration for perhaps the best story in the collection, “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The choice of both title and art for this book did well to make it a best-seller: the word “flappers” and the art showing a young girl cropping her hair in the latest style are at once attractive and provocative, easily capturing the... [more The Artists Behind F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Dust Jackets: Part I (1920-1923)]

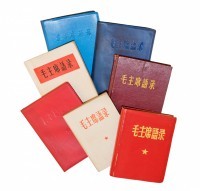

The 1960s was a decade of both discovery and protest, riots and revolutions, from anti-war marches, assassinations of world leaders, man's first landing on the moon, and the birth of a new brand of music led by The Beatles. Change was in the air and nowhere was it more obvious than in modern China with the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in August 1966. But more than two years earlier, before Chairman Mao ordered his Red Guards to restructure Society and re-educate intellectuals, there was the "Little Red Book" – a series of useful quotations gathered from Mao's earlier lectures and writings that would help guide his countrymen and women to deal with problems covering all aspects of daily life. The size of the book was small enough to fit inside a shirt pocket so it could be flush against the heart. Its phenomenal popularity may be because the book was essentially an unofficial requirement for every Chinese citizen to own, to read, to memorize and to carry copies at all times during the last ten years of Mao's rule, which essentially comprised the Cultural Revolution. Studying the book was not only required in schools but it also became a standard practice in the workplace. All units, in the industrial, commercial, agricultural, civil service, and military sectors, organized group sessions for the entire workforce to study the book during business hours that often extended into evening discussion meetings. During the middle to late 1960s, the book became the single most... [more 1964: The Little Red Book]

To mark the 75th Anniversary of 1939, we've asked some ABAA members to discuss publications from that momentous year. Garrett Scott, a prominent Ann Arbor bookseller, offers a divagation upon At Swim-Two-Birds, Flann O'Brien's proto-post-modern first book– published in 1939. Biographical reminiscence, part the first: Sometime in 1991, I had taken up temporary residence in a storage closet in a university-owned cooperative house. This was during a period in college in which I was neither enrolled in any classes nor strictly speaking in the eyes of the university a resident of the university-owned cooperative house. The storage closet was situated within one easy extension-cord's length of a hallway electrical outlet and thus easily outfitted with a small fan and a reading lamp and a clock radio. A spare mattress fit neatly between the stacks of cardboard boxes and assorted lumber. The storage closet had the added utility of providing my then-girlfriend with a place to lodge me when she sought respite from my company. One evening prior to another bout of rustication she endeavored to occupy me by handing me a paperback copy of a book written by a man named Flann O'Brien, a member of the Irish nation. The name of the book was At Swim-Two-Birds. She told me the book was about a college student trying to write a book. Nature of her summary: Perfunctory. The figure of speech she had inadvertently employed: Understatement. And thus with nothing but the hum of the fan beside my mat... [more 1939: At Swim-Two-Birds]