On September 25, 1789, as the momentous first Federal Congress drew to its close in New York, the new national capital, Representative Elias Boudinot introduced a resolution calling on President Washington to “recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer . . . acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”

A leading opponent of the resolution, Thomas Tudor Tucker, asked, “Why should the president direct the people to do what, perhaps, they have no mind to do?” The skeptical congressman noted that the people “may not be inclined to return thanks for a constitution until they have experienced that it promotes their safety and happiness.” He also argued that it was a religious matter and thus proscribed to the new government. Regardless, the House passed the resolution — one of their last pieces of business before completing the proposed Bill of Rights. The Senate concurred three days later, and a delegation was sent to meet the president. Washington, who had in fact anticipated the question in a letter to James Madison a month earlier, readily agreed.

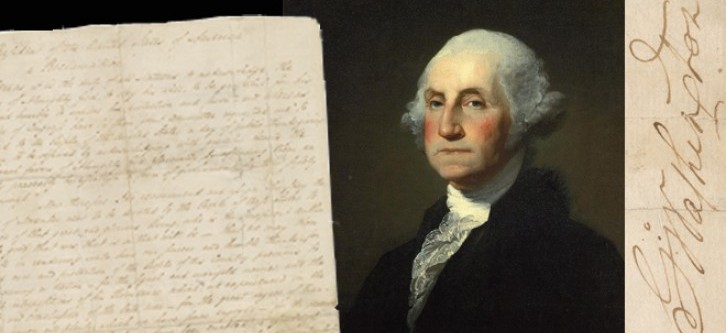

On October 3, President Washington signed the document offered here, America’s first Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation. Washington employed the exact language of the resolution to begin his proclamation, though he went further, giving thanks for “tranquility, union, and plenty” and asking the Almighty to guide the new nation’s leaders and government. He used the same approach a year later when he wrote what is now one of his most celebrated letters: “For happily the Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, [and] requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

Washington willingly echoed Moses Seixas’s stance on tolerance and added to it, just as he did in his Thanksgiving Proclamation when asking the Almighty “To render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and Constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed.”

.jpg)

George Washington. Manuscript Document Signed as President. Proclaiming “Thursday the 26th day of November” as “a day of thanksgiving and prayer.” New York, N.Y., October 3, 1789. 1 p., 9-5⁄8 x 14-5⁄8. The text of this, and the other known copy (acquired by the Library of Congress in 1921) was penned by William Jackson, a personal secretary to the president and previously the secretary to the Constitutional Convention. (Photo credit: Seth Kaller, Inc.)

Establishing the National Holiday

The American public enthusiastically accepted Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation. Newspapers printed it, citizens celebrated across the country, and churches used the occasion to solicit donations for the poor. George Washington personally responded, contributing $25. In 1795, noting “the unexampled prosperity of all classes of our citizens,” Washington issued his only other Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation, calling on Americans to “acknowledge our many and great obligations to Almighty God and to implore him to continue and confirm the blessings we experience.”

John Adams and James Madison would also issue Thanksgiving Proclamations, but days of Thanksgiving typically remained state holidays. Abraham Lincoln was the next president to issue national Thanksgiving Proclamations. He began by closing government departments for a day in 1861, and in March 1863, he called for a day of “national humiliation, fasting, and prayer.” He issued another, assigning August 6, 1863, as a day of “National Thanksgiving.” Soon after, Lincoln was moved by a letter from Sarah Josepha Hale, who had lobbied the four prior presidents unsuccessfully to make Thanksgiving a third national holiday in addition to Independence Day and Washington’s Birthday. On October 3, 1863, exactly 74 years after George Washington’s proclamation, Lincoln established the fourth Thursday in November as a national day of Thanksgiving, setting the precedent that remains to this day.

----------

This historic document is offered by Seth Kaller, Inc., more information...

.jpg)