The recent posts by Peter Stern, Rusty Mott, and Joyce Kosofsky made me wish I was in Boston last weekend for the book fair, but circumstances conspired against it this year.

However, in a spirit of Bostonian collegiality, I thought I’d write about something I have noticed in the past here in Europe: the false Boston imprint. Last year, Mitch Fraas at the University of Pennsylvania made a study of fictitious American imprints before the year 1800. By his count, there were 173 European books which purported to have been published in America, but weren’t. The vast majority of those (136) took Philadelphia as their imprint, but Boston comes second, with 19. These ‘not Boston’ books are quite scarce, but you do see them from time to time. Here are a couple of examples.

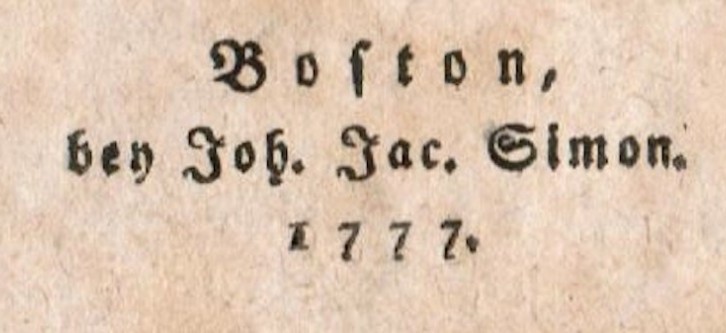

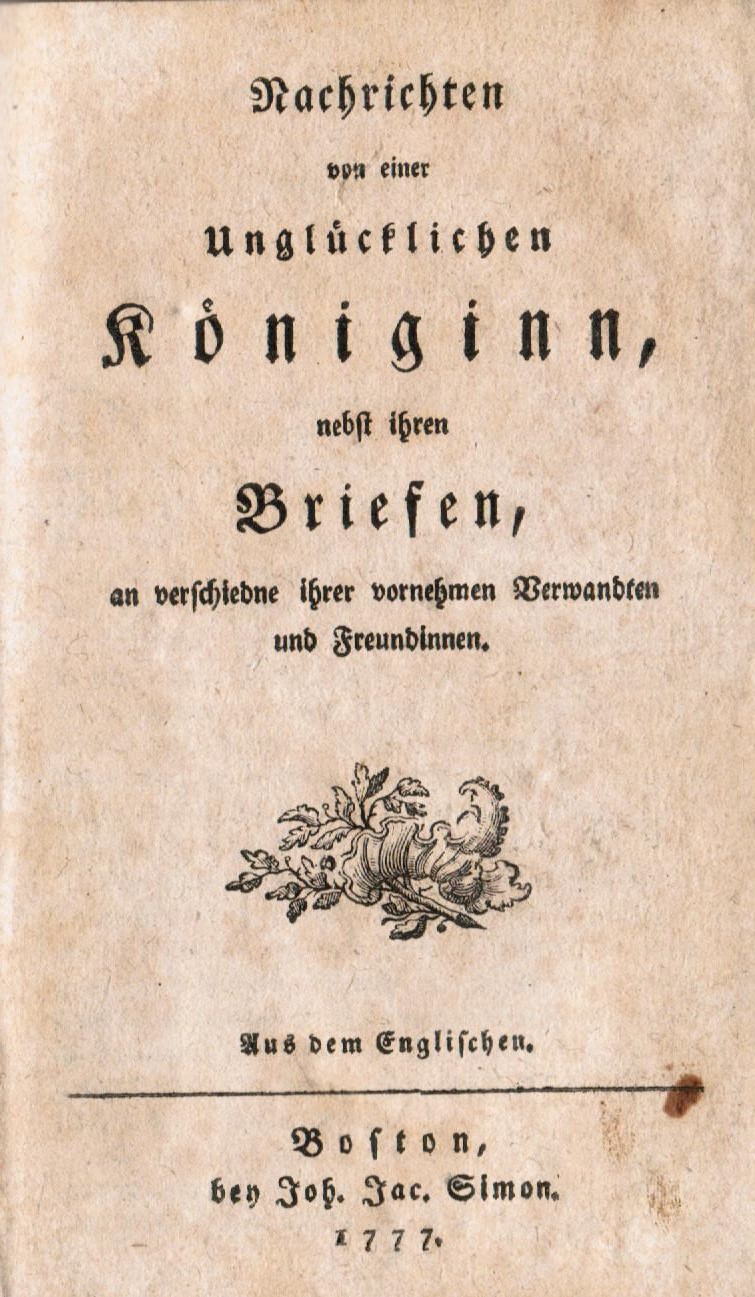

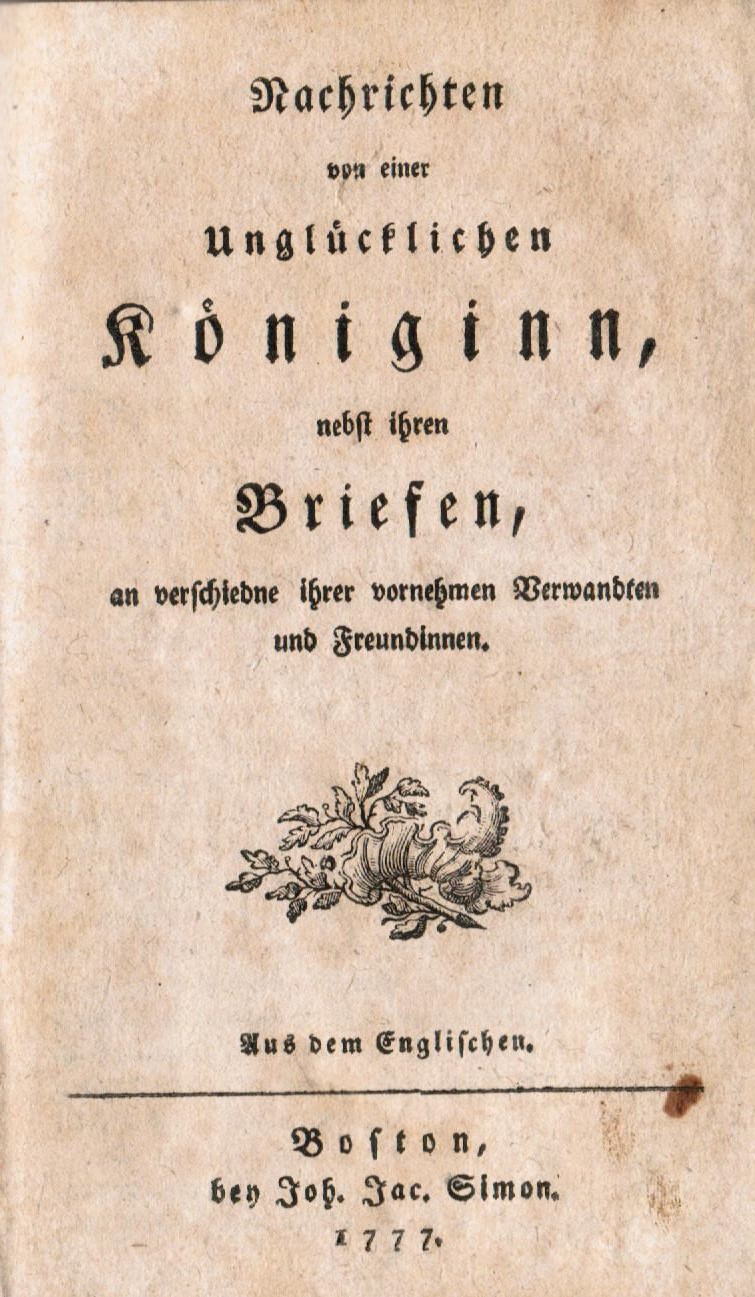

This is a translation of the spurious Memoirs of an unfortunate Queen, originally published in 1776 by the London bookseller, John Bew. The public bought up two editions within the year, and Bew also brought out one in French. The 'unfortunate queen' was Caroline Matilda (1751–1775), the youngest sister of George III who was married off to her cousin, Christian VII of Denmark, when she was only 15. It was not a happy marriage. Christian was a mentally unstable philanderer who claimed it was ‘unfashionable to love one’s wife’, and Caroline eventually drifted into an affair with the royal physician Johan Struensee, a rising star at the Danish court who effectively ruled the country for ten months as Christian’s mental health worsened. Caroline and Struensee were arrested in January 1772; Caroline’s marriage to Christian was dissolved a few months later, and Struensee was executed. In May, Caroline was deported, without her two children, to Celle in Germany (the probably place of printing for this German translation), where she was supported by the Hanoverian exchequer. She died three years later, of scarlet fever, aged 23.

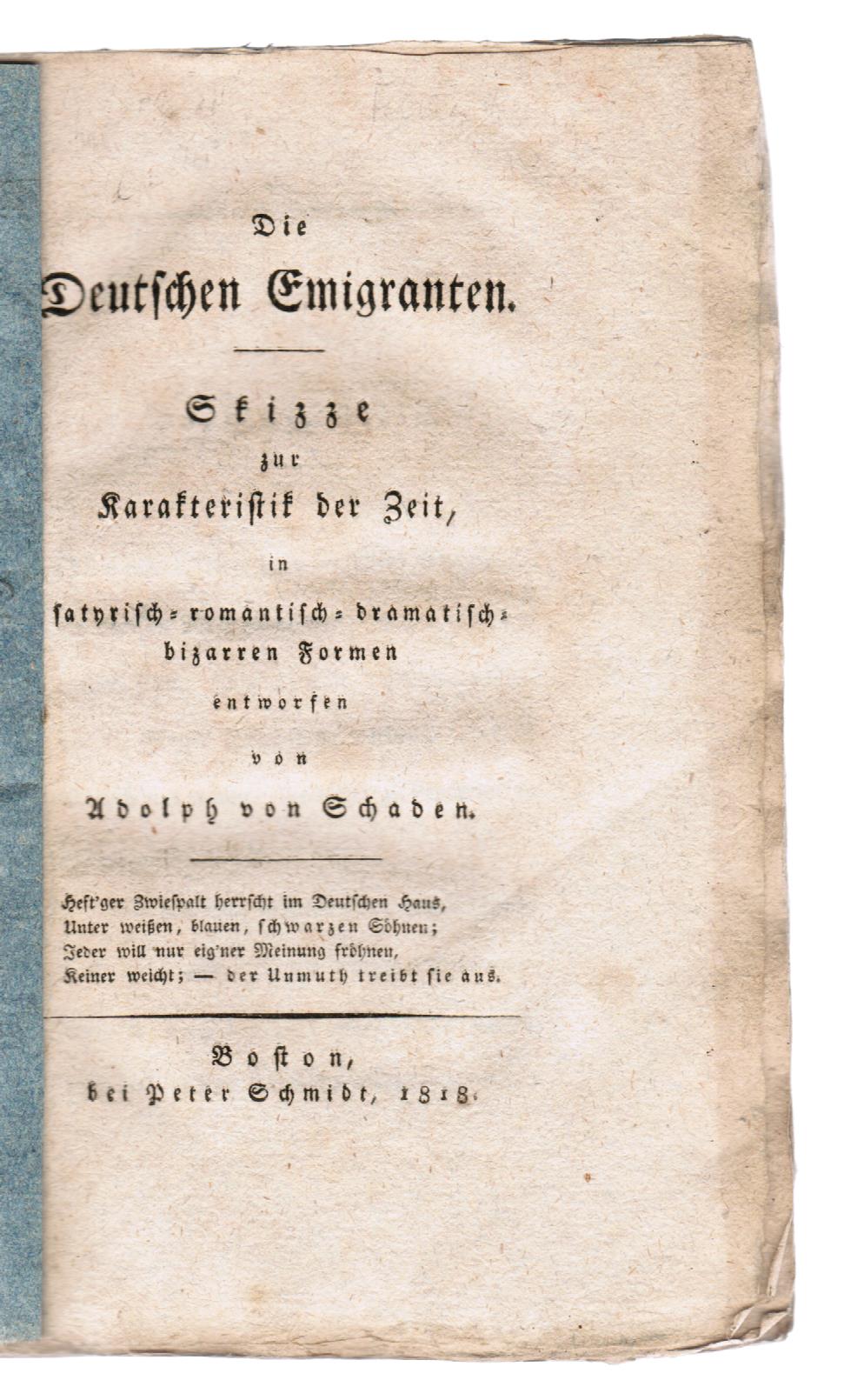

It’s not very clear why the Germans should have used a ‘Boston’ imprint here, but my other example is a bit more obvious: it’s a satire on on emigration to America.

The author couches his satire in the form of a play, set on the deck of a merchantman bound for America. Partly in prose, partly in verse, the ship’s captain leads discussions with representatives from around the German-speaking world, all driven to emigrate due to conditions in post-Napoleonic Europe: a former officer from Hesse, an Austrian parson, a speculator from the Rhineland, a Frankfurt Jew, etc. The conversations range from education (one of the women on board, inspired by Pestalozzi, wants to set up a girls’ school) and economics (the Saxon waxes lyrical on Adam Smith and Le Mercier), to books (a printer from Baden has brought a set of type with him, with the intention of issuing reprints of British classics). America is depicted as an Eldorado flowing with milk and honey (sic) before, as they near other side of the Atlantic, they realise how much it stinks. Schaden (1791–1840), a young Berlin playwright, gives his view of emigration in his ‘prefatory sigh’: "We hereby freely and publicly acknowledge German emigrants to be people who have sadly lost their way, and that our satirical sketch has the intention to scourge no one but these deranged folk…"

How things change. I'm sure there were plenty of Europeans at the Hynes last weekend.