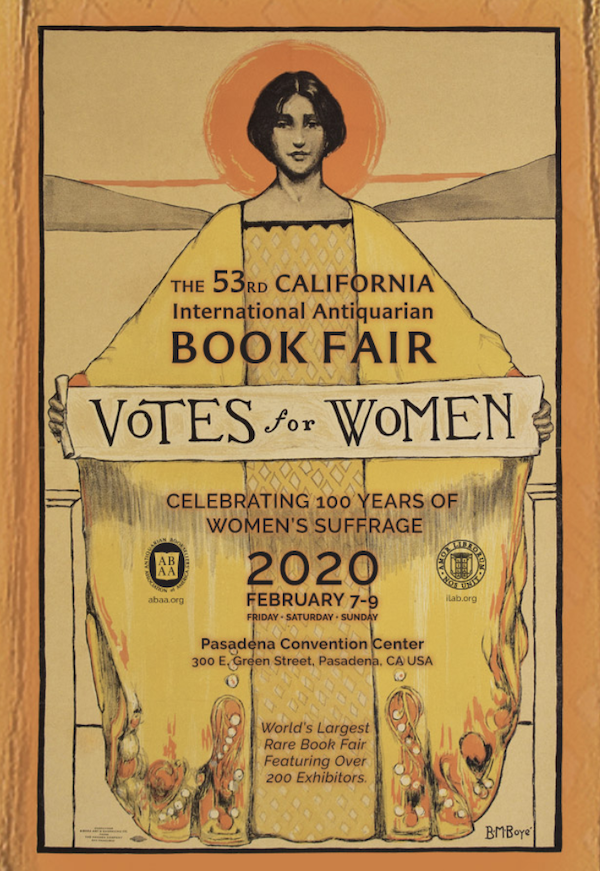

In commemoration of the centennial of the 19th Amendment, the 53rd California International Antiquarian Book Fair, February 7-9, 2020 in Pasadena, will feature a special exhibit and panel discussions on the women’s suffrage movement. This celebration will highlight the contributions of successive generations of women, from protofeminists like Mary Wollstonecraft, to the abolitionists and the temperance movement, through pioneering crusaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the suffragettes who eventually won the vote, as well as those activists who have continued the fight for equal rights in the 21st century. Among these women is the California artist whose iconic artwork adorns the book fair’s poster.

Bertha Margaret Boye (1883–1931) was born in Oakland, the daughter of German immigrants. Her father was a cabinet maker, and her mother a homemaker. She was the middle of three sisters; the oldest worked as a nurse and her younger sister was a portrait painter. Boye had just completed studies at the famous Mark Hopkins Art Institute in San Francisco when she entered and won the poster contest sponsored by the College Equal Suffrage League in 1911. She received a $50 prize for her design, which was reproduced on cards, handbills, and publicity stamps.

Boye’s design was the precise image leaders of the movement sought. The first suffrage campaign in California, in 1896, failed. When conditions suddenly changed in 1910 and a progressive Republican administration was swept into power, woman suffragists seized the opportunity. They had only eight months to organize their campaign and win over the male voters deciding the issue who were more "amused, indifferent and incredulous" than hostile, wrote suffrage leader Louise Wall. "It seemed best for us to put forth positive arguments of a hopeful, constructive sort rather than arguments that ended in criticism or irony...”

Boye’s design reflects this sentiment and is in keeping with the suffrage posters of the 1910s, which tended to be conservative in their rhetoric and visual style, according to art historian Paula Harper. While many 19th century feminists had taken a revolutionary stance against society’s norms and institutions, the suffragists of the 1910s did so by suggesting that the women’s vote would strengthen rather than destroy the existing culture.

Symmetrical in design, the image reinforces a sense of serenity with a feminine figure at its center and an orb rising behind her head as both sun and halo. The poster’s slogan, “Votes for Women,” appears not as a battle cry, but as an unassailable truth, an “inalienable right” whose time had come. For an entire week in August 1911, merchants throughout San Francisco displayed it in their shop windows, accompanied by festive decorations in suffrage yellow which supporters called “the color of success.” The image remains an enduring symbol of the triumphant California campaign, which was an important precursor to the passage of the 19th Amendment (1920), granting women the right to vote in the United States.

While Boye’s design, upon later reflection, may have been the demure image needed to carry the day, one could hardly view the artist herself as a shrinking violet. One might say she knew her worth. Boye first made headlines in 1905 in San Francisco when she sued the editor of the Blue and Gold, UC Berkeley’s student newspaper, demanding payment of $25 for a drawing that was published. As no writer or artist had ever been paid for similar work and Boye was part of the art staff, the editor was incredulous.

Boye went on to have a successful and illustrious artistic career. She was selected by H.P. Baldwin of Maui, Hawaii to design a bronze drinking fountain as a memorial to his grandson. The 5 ½ foot-tall sculpture of a child holding a cup was destroyed in San Francisco’s great fire in 1906, but it was recast a year later and installed at a prominent intersection on the island. She provided the winning artwork in 1910 for a women’s fashion poster contest and illustrated two books: Dotty Seaweed Verses by Cornell Hughes, published in 1908 by Philopolis Press, San Francisco; and Jingles for Singles, or a Mother’s Goose for Lovers’ Use, published in 1910 by Ida Juillerat as a holiday gift book.

Boye attended Mark Hopkins on scholarship for seven years, then traveled to Europe to continue her studies. In Denmark, she designed patterns for a famous line of Danish lace, but returned to California at the outbreak of World War I. She settled in Ukiah, where she led a quiet life, teaching art to children and working on pottery and sculpture of Native Americans and animals. Curious about her work, Bret Harte visited Boye at her Ukiah art studio, recording his impressions in the January 1924 issue of the Overland Monthly: “Then more fully did I realize the charm of truth and simplicity that hold Bertha Boye at her studio in the shadow of the western hills, while at the same time will I urge and hope that she may place her work before an appreciative public.” In 1930, Boye returned to Europe for a summer art conference, suddenly fell ill, and died in Calais, France.

-- Jen Johnson is the co-owner of johnson rare books & archives, ABAA/ILAB