1966 · Europe and the Americas

by [Wireless Technology - Marconi Company] Round, Henry Joseph, et al.

Europe and the Americas, 1966. Generally fine. Henry Joseph Round (1881–1966) was a pioneer of wireless technology. He began his career under Guglielmo Marconi in the early twentieth century and enjoyed a productive, decades-long career in the field, filing 117 patent applications and receiving the Military Cross in 1818 and the Radio Club of America’s Armstrong gold medal in 1952. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that “the electronics industry owes him a large debt as its most prolific inventor to date.” [1]

Offered here is the only known collection of archival material belonging to Round apart from material held in the Marconi archives. The group includes Round’s notebooks, incoming correspondence from several high-profile scientists and others, a collection of letters and postcards sent home from North America in his period working there with Marconi, and an apparently unpublished autobiographical sketch describing his career through 1926. The notebooks should be of significant interest to historians of wireless technology, though their technical nature prevents us from describing the scientific content in great detail. The material from Round’s period in North America is particularly strong, with nearly 250 pp. of letters written home describing his work with Marconi, and postcards from the same period.

On joining the Marconi Company in 1902, Round was sent to Long Island; he worked between there, Chicago, Wellfleet, and Newfoundland, performing experiments with dust cores and direction finding. He would work on and off with the American Marconi Company until his recall to England, some time before 1911, to work with Guglielmo Marconi personally. In these letters, Round tells his family in detail about his work and especially about the financial and managerial struggles of the Marconi Company. In an early letter, he writes:

“Wireless is getting a bad name through bad management and failures The engineers are there but the financial and managing part is bad especially in the English company We get orders to throw up experiments when only half way through it is sometimes very disheartening However I am glad I am going on a big job it shows Im beginning to be recognized and you bet I shall do my best” (No Date, c.1902)

Round had just been reassigned from Long Island to Chicago to work on “a very secret affair”, “one of the stiffest jobs wireless has ever undertaken”. He arrives there in 1903; the job is to set up wireless stations in Chicago and Milwaukee to generate interest in the company. He explains to his parents:

“These stations are for the purpose of selling stock: showing the working of wireless to the Chicago millionaires – I know a good few already some are gentlemen and some are not mostly not. Money money money Thats all they are This is a heartbreaking money spending town.” (July 15, 1903)

Round first meets Marconi that September, and tells his parents he was “agreeably surprised – thought I was going to meet a snob instead met a perfect gentleman”, and that Marconi was “good looking” and “very humorous” (September 29, 1903). By this point, Round was tinkering in his spare time:

“Wireless work[s] well here now got some devices of my own which are highly commended by New York office nothing very important though Im working on a new thing wireless here quite my own for recording the Transatlantic signals rough experiments very successful Signals over the Atlantic have been too faint to record although they are easily read by sound” (September 29, 1903)

In 1901, Marconi had succeeded in sending a radio signal from Cornwall, England, to Newfoundland; in January of 1903 he sent a full radio message from Wellfleet to Canada and from there to England. Nonetheless, the trans-Atlantic system needed work that would continue—and continue to frustrate Round—into the 1910s.

Round’s main source of frustration, though, is the financials of the Marconi Company. In 1903 he leaves the company to work for Bell Telephone and, during this time, tries to sell an invention of his own to the Marconi Company:

“I am in negotiation with Bradfield to sell the Marconi Co a new invention in wireless [...] I have got something which is definitely new and differes [sic] entirely from the present wireless system I made some experiments last Sunday at Babylon which were entirely successful over 3 miles with only crude apparatus If the Marconi people werent so hard up Id have a chance to sell it to them.” (1903)

In 1904, Round returns to Marconi, which is then “having a big fight with the U.S. government”; the government had “a shot at putting [wireless stations] up themselves and have failed miserably" and was now “having an attempt to get control of all wireless stations by act of Congress” (1904). Later in the year Round leaves Marconi again, “for good” (1904), to work for the New York & New Jersey Telephone Company; and then returns to Marconi yet again in 1905 or 1906. During this time he creates an early wireless radio telephone:

“During my year with the telephone company I managed to stock my brain with a fair amount of telephone knowledge and with the wireless knowledge I had – Ive succeeded in getting out a wireless telephone – guess this will puzzle you but it means we are talking over several miles without the assistance of wires actual conversation I mean not telegraphing” (No Date, c. 1906)

Nonetheless, the Marconi Company is still doing poorly financially:

“The whole Marconi affair is being so badly managed by the English general manager who seems to have complete control that the system is getting quite a bad name Warships from all nations have been visiting here lately and on the Argentine and Brazilian ships the Marconi apparatus on board was absolutely useless on account of bad management [...] I spose one reason for worry is that the company is fairly short of funds [...] Everybody is getting pretty short of money now due to the scene given by the investigation into the Trusts and railways Our company lately saved $100,000,000 bonds for further developments and altho’ it has always paid huge dividends noone would take the bond up – so that this year all development is stopped”. (June 7, 1907)

Round also pins a lot of the company’s financial struggle on patent law, for which “They have spent over ¼ million dollars already [...] preventing us working in other fields” (No Date).

The remainder of his time with the American Marconi Company, before his recall to England, followed the same pattern: great improvements in transmission distance alongside frustrating performance and financial strain on the company; Round often laments to the effect that “If Marconi would only buck up and get the transatlantic working we should have no difficulty” selling stock (No Date).

A letter from a colleague in Wellfleet, C.H. Taylor, inquiring about Round’s experiments illustrates the technical nature of much of the archive:

“How could you join those condensers to any part of the coil? You needed – for your definite wavelength – a value of capacity to ground of say C. Could you join up 10 condensers of each 1/10 C to the coil or 20 condensers each 1/20 C & so on [...]?” (March 18, 1907)

Round had returned to England by 1911, but in 1912 was sent to South America, where he pioneered the use of different wavelengths for daytime versus nighttime communication to deal with signal attenuation in the dense Amazon jungle. Back in England around 1913, he designed and tested a valve system—and a transmission system and auto-heterodyne circuit (Round’s patents are numerous)—and, at the outbreak of the First World War, worked on “sensitive receivers to intercept enemy messages” (No Date; letter to Sir George Cockerill). Round’s receivers were so sensitive that they were able to intercept “messages sent between the German ships in the Bight [...] which they considered would only travel about 5 miles” – leading to the Battle of Jutland.

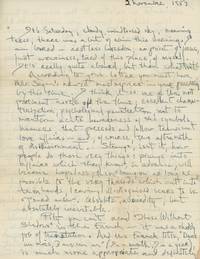

Round was appointed chief of the Marconi Research Group in 1921 and set up a private consulting practice in 1931. Though the majority of Round’s letters in this archive were written during his time in North America, many of his notebooks date from this later period of his career. Some include what seem to be article manuscripts, such as a notebook titled “Power Control by Mechanical Means”; most contain a mixture of drawings, notes, musings, and to-dos, including “Call Gordon Smith re. C.N. Test”, “salt and pepper”, and notes about rhodium- versus silver-plated strips. In his notebooks, Round sometimes narrates his research process; for instance, in a notebook likely from the 1940s, he writes:

“The strip radiation principle becomes more difficult to carry out as the frequency is lowered and once or twice I have nearly determined to give it up until I get a real hunch on a new method. There are a number of points at which I have stuck. Of course I can blindly build the required 2” strip but I feel that just carrying on the [diversions] of the 16000~ one which is pretty successful is a wrong way, it does not guide one to still lower frequencies. [...] It did not seem reasonable to use the 4 mil nickel I was using on the higher frequencies – it is not only too expensive but its lack of rigidity in long lengths meant considerable difficulty in solidifying up the blocks. I purchased some 15 mil stuff and started experimenting with this on 8000~ [...]”

In a notebook from the 1950s, Round gives a concise summation of his philosophy:

“I like my opinion to be taken preference to another opinion particularly in a subject I have studied well but I do not think my opinion should be taken against anothers ‘facts’ unless the latter are under suspicion. The only true knowledge we have is ‘fact’ or experimental knowledge.”

The last of Round’s 117 patent applications was filed in 1962, when Round was eighty-one years old. He died in 1966. This group is the only known collection relating to Round, and provides a significant research opportunity for historians of science and wireless technology, and of the Marconi Company.

[1] Peter Baker and Betty Hance, “Round, Henry Joseph,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/35846.

Provenance: Sold at Sotheby's, 17 July 1984, lot 411; Acquired by Auger Down Books in partnership with Open Boat Booksellers at Christies, 15 December 2023.

Full inventory as follows:

Box 1: Various Letters and Photographs from Round’s Period in America and Early Career, 1900-1922; Incoming Correspondence, 1944-1966; Handwritten and Typed Manuscript Material, 1926-1966.

1900-1920s folder: Letters from Round to family in England, 1901-1910: 52 complete, 243pp.

12 partial, 37pp.

From New York City; Babylon, Long Island; Chicago; Mobile Alabama; among others.

Describing his first impressions of America, his first opportunity to meet Marconi, the work on setting up various wireless stations in the US and the eastern shore of Canada, his independent inventions and writing work for electronic periodicals, the patent disputes of the Marconi company, including with the United States government.

Incoming scientific correspondence folder, 1906-1922, 14 letters.

WW1, seven mixed pieces, mostly correspondence.

Notes/earlier miscellaneous folder, including draft of a letter to Marconi himself, a 1903 Marconigram, shipboard dinner menus and ephemera, material related to Round's patents and his popular science work, as well as various Marconi company materials c1900-1910, approximately 25 pieces altogether.

Photos, 94 photographs and negatives, many annotated to reverse, apparently from earlier period with Marconi, including 3 photos related to the ship Mafalda, some apparently with Marconi's annotations.

Incoming correspondence, 1944-1966, 109 letters, many multi page, including scientific material, including a group of 15 letters with 10 additional pages of notes by Round related to experimental work with medical use of radiolocation for patients at St. Dunstan's, as well as retrospective and historical material related to the early days of radio and wireless. With substantial groupings of letters by George E. Burghard (6), Tom J. Styles of Columbia University (15), and Lloyd Espenschied of Bell Labs (15).

Handwritten and typed manuscript material, 1926-1966, over 200 pages, many scientific pieces with additional notes, diagrams, and calculations, as well as historical material chronicling his time with the Marconi Company, including a 21 page autobiographical sketch of his scientific career through 1926.

Miscellaneous paper and ephemera, including some photocopied material, post-1926, highlights include fine press menus for 1929 testimonial dinner given for Round by the Radio Club of America, one with signatures of over 25 guests, and a similar 1952 menu by the same organization for awarding the Armstrong Medal to Round; as well as a few scientific offprints, among clippings, photocopies, and other printed material.

Boxes 2 & 3: Thirty-Three Manuscript Scientific and Technical Notebooks.

Box 2: Scientific Notebooks, 1950s.

Numbered small notebooks, 1-21, 23, 30, each approximately with 50-150 filled in pages, mixing scientific notes with calculations and diagrams

1: 1952, 2: No date (ND), 3: ND, 4: 1954, 5: ND, 6: 1954, 7: ND, 8: ND, 9: ND, 10: ND, 11: ND, 12: ND, 13: ND, 14: ND, 15: ND, 16: ND, 17: ND, 18: 1957, 19: 1957, 20: ND, 21: ND, 23: 1959, 30: 1959

Box 3: Various Notebooks Documenting Round’s Scientific Work, 1906-1948.

Unnumbered, flip open, titled the scheme book, 1906.

Unnumbered, medium red notebook: no date.

Pulse generator: no date.

Unnumbered, medium black notebook with 4000 etched cover, 1948.

Unnumbered, small to medium red notebook, unreadable text to cover, 1958.

Unnumbered, larger black notebook, corner missing from cover: no date.

Unnumbered, larger dark red notebook, staining bottom right cover: 1941

#3, larger notebook, red, 1939.

#5, larger notebook, no date.

Unnumbered, wraps, titled power control by mechanical means, no date.

Box 4: Patents, 1908-1959; Magazines from the 1920s.

Patents: 85 printed patent specifications, some with Round's notes, 1908-1959, with additional single 1959 filled in patent form with typewritten 5 page addendum, along with small group of photocopies of Round's patents.

Magazines: 9 copies of Wireless Magazine and Amateur Wireless and Modern Wireless with articles by Round, 1927-29, some lacking covers, with rough tape repairs.

Box 5: Books, Bound Printed Material, Postcards.

Books and other bound printed material:

Postcards: circa 1900 through 1914, majority 1903-1906 from Round's trip through North America, including New England, New York, Chicago, Birmingham, Alabama, and Nova Scotia, and serving as a detailed itinerary of places visited while traveling on behalf of the Marconi Company, with some later European and Brazilian related.

48 with notes by Round, ranging from single lines to full postcards.

115 no text, most sent with postal markings. (Inventory #: List2746)

Offered here is the only known collection of archival material belonging to Round apart from material held in the Marconi archives. The group includes Round’s notebooks, incoming correspondence from several high-profile scientists and others, a collection of letters and postcards sent home from North America in his period working there with Marconi, and an apparently unpublished autobiographical sketch describing his career through 1926. The notebooks should be of significant interest to historians of wireless technology, though their technical nature prevents us from describing the scientific content in great detail. The material from Round’s period in North America is particularly strong, with nearly 250 pp. of letters written home describing his work with Marconi, and postcards from the same period.

On joining the Marconi Company in 1902, Round was sent to Long Island; he worked between there, Chicago, Wellfleet, and Newfoundland, performing experiments with dust cores and direction finding. He would work on and off with the American Marconi Company until his recall to England, some time before 1911, to work with Guglielmo Marconi personally. In these letters, Round tells his family in detail about his work and especially about the financial and managerial struggles of the Marconi Company. In an early letter, he writes:

“Wireless is getting a bad name through bad management and failures The engineers are there but the financial and managing part is bad especially in the English company We get orders to throw up experiments when only half way through it is sometimes very disheartening However I am glad I am going on a big job it shows Im beginning to be recognized and you bet I shall do my best” (No Date, c.1902)

Round had just been reassigned from Long Island to Chicago to work on “a very secret affair”, “one of the stiffest jobs wireless has ever undertaken”. He arrives there in 1903; the job is to set up wireless stations in Chicago and Milwaukee to generate interest in the company. He explains to his parents:

“These stations are for the purpose of selling stock: showing the working of wireless to the Chicago millionaires – I know a good few already some are gentlemen and some are not mostly not. Money money money Thats all they are This is a heartbreaking money spending town.” (July 15, 1903)

Round first meets Marconi that September, and tells his parents he was “agreeably surprised – thought I was going to meet a snob instead met a perfect gentleman”, and that Marconi was “good looking” and “very humorous” (September 29, 1903). By this point, Round was tinkering in his spare time:

“Wireless work[s] well here now got some devices of my own which are highly commended by New York office nothing very important though Im working on a new thing wireless here quite my own for recording the Transatlantic signals rough experiments very successful Signals over the Atlantic have been too faint to record although they are easily read by sound” (September 29, 1903)

In 1901, Marconi had succeeded in sending a radio signal from Cornwall, England, to Newfoundland; in January of 1903 he sent a full radio message from Wellfleet to Canada and from there to England. Nonetheless, the trans-Atlantic system needed work that would continue—and continue to frustrate Round—into the 1910s.

Round’s main source of frustration, though, is the financials of the Marconi Company. In 1903 he leaves the company to work for Bell Telephone and, during this time, tries to sell an invention of his own to the Marconi Company:

“I am in negotiation with Bradfield to sell the Marconi Co a new invention in wireless [...] I have got something which is definitely new and differes [sic] entirely from the present wireless system I made some experiments last Sunday at Babylon which were entirely successful over 3 miles with only crude apparatus If the Marconi people werent so hard up Id have a chance to sell it to them.” (1903)

In 1904, Round returns to Marconi, which is then “having a big fight with the U.S. government”; the government had “a shot at putting [wireless stations] up themselves and have failed miserably" and was now “having an attempt to get control of all wireless stations by act of Congress” (1904). Later in the year Round leaves Marconi again, “for good” (1904), to work for the New York & New Jersey Telephone Company; and then returns to Marconi yet again in 1905 or 1906. During this time he creates an early wireless radio telephone:

“During my year with the telephone company I managed to stock my brain with a fair amount of telephone knowledge and with the wireless knowledge I had – Ive succeeded in getting out a wireless telephone – guess this will puzzle you but it means we are talking over several miles without the assistance of wires actual conversation I mean not telegraphing” (No Date, c. 1906)

Nonetheless, the Marconi Company is still doing poorly financially:

“The whole Marconi affair is being so badly managed by the English general manager who seems to have complete control that the system is getting quite a bad name Warships from all nations have been visiting here lately and on the Argentine and Brazilian ships the Marconi apparatus on board was absolutely useless on account of bad management [...] I spose one reason for worry is that the company is fairly short of funds [...] Everybody is getting pretty short of money now due to the scene given by the investigation into the Trusts and railways Our company lately saved $100,000,000 bonds for further developments and altho’ it has always paid huge dividends noone would take the bond up – so that this year all development is stopped”. (June 7, 1907)

Round also pins a lot of the company’s financial struggle on patent law, for which “They have spent over ¼ million dollars already [...] preventing us working in other fields” (No Date).

The remainder of his time with the American Marconi Company, before his recall to England, followed the same pattern: great improvements in transmission distance alongside frustrating performance and financial strain on the company; Round often laments to the effect that “If Marconi would only buck up and get the transatlantic working we should have no difficulty” selling stock (No Date).

A letter from a colleague in Wellfleet, C.H. Taylor, inquiring about Round’s experiments illustrates the technical nature of much of the archive:

“How could you join those condensers to any part of the coil? You needed – for your definite wavelength – a value of capacity to ground of say C. Could you join up 10 condensers of each 1/10 C to the coil or 20 condensers each 1/20 C & so on [...]?” (March 18, 1907)

Round had returned to England by 1911, but in 1912 was sent to South America, where he pioneered the use of different wavelengths for daytime versus nighttime communication to deal with signal attenuation in the dense Amazon jungle. Back in England around 1913, he designed and tested a valve system—and a transmission system and auto-heterodyne circuit (Round’s patents are numerous)—and, at the outbreak of the First World War, worked on “sensitive receivers to intercept enemy messages” (No Date; letter to Sir George Cockerill). Round’s receivers were so sensitive that they were able to intercept “messages sent between the German ships in the Bight [...] which they considered would only travel about 5 miles” – leading to the Battle of Jutland.

Round was appointed chief of the Marconi Research Group in 1921 and set up a private consulting practice in 1931. Though the majority of Round’s letters in this archive were written during his time in North America, many of his notebooks date from this later period of his career. Some include what seem to be article manuscripts, such as a notebook titled “Power Control by Mechanical Means”; most contain a mixture of drawings, notes, musings, and to-dos, including “Call Gordon Smith re. C.N. Test”, “salt and pepper”, and notes about rhodium- versus silver-plated strips. In his notebooks, Round sometimes narrates his research process; for instance, in a notebook likely from the 1940s, he writes:

“The strip radiation principle becomes more difficult to carry out as the frequency is lowered and once or twice I have nearly determined to give it up until I get a real hunch on a new method. There are a number of points at which I have stuck. Of course I can blindly build the required 2” strip but I feel that just carrying on the [diversions] of the 16000~ one which is pretty successful is a wrong way, it does not guide one to still lower frequencies. [...] It did not seem reasonable to use the 4 mil nickel I was using on the higher frequencies – it is not only too expensive but its lack of rigidity in long lengths meant considerable difficulty in solidifying up the blocks. I purchased some 15 mil stuff and started experimenting with this on 8000~ [...]”

In a notebook from the 1950s, Round gives a concise summation of his philosophy:

“I like my opinion to be taken preference to another opinion particularly in a subject I have studied well but I do not think my opinion should be taken against anothers ‘facts’ unless the latter are under suspicion. The only true knowledge we have is ‘fact’ or experimental knowledge.”

The last of Round’s 117 patent applications was filed in 1962, when Round was eighty-one years old. He died in 1966. This group is the only known collection relating to Round, and provides a significant research opportunity for historians of science and wireless technology, and of the Marconi Company.

[1] Peter Baker and Betty Hance, “Round, Henry Joseph,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/35846.

Provenance: Sold at Sotheby's, 17 July 1984, lot 411; Acquired by Auger Down Books in partnership with Open Boat Booksellers at Christies, 15 December 2023.

Full inventory as follows:

Box 1: Various Letters and Photographs from Round’s Period in America and Early Career, 1900-1922; Incoming Correspondence, 1944-1966; Handwritten and Typed Manuscript Material, 1926-1966.

1900-1920s folder: Letters from Round to family in England, 1901-1910: 52 complete, 243pp.

12 partial, 37pp.

From New York City; Babylon, Long Island; Chicago; Mobile Alabama; among others.

Describing his first impressions of America, his first opportunity to meet Marconi, the work on setting up various wireless stations in the US and the eastern shore of Canada, his independent inventions and writing work for electronic periodicals, the patent disputes of the Marconi company, including with the United States government.

Incoming scientific correspondence folder, 1906-1922, 14 letters.

WW1, seven mixed pieces, mostly correspondence.

Notes/earlier miscellaneous folder, including draft of a letter to Marconi himself, a 1903 Marconigram, shipboard dinner menus and ephemera, material related to Round's patents and his popular science work, as well as various Marconi company materials c1900-1910, approximately 25 pieces altogether.

Photos, 94 photographs and negatives, many annotated to reverse, apparently from earlier period with Marconi, including 3 photos related to the ship Mafalda, some apparently with Marconi's annotations.

Incoming correspondence, 1944-1966, 109 letters, many multi page, including scientific material, including a group of 15 letters with 10 additional pages of notes by Round related to experimental work with medical use of radiolocation for patients at St. Dunstan's, as well as retrospective and historical material related to the early days of radio and wireless. With substantial groupings of letters by George E. Burghard (6), Tom J. Styles of Columbia University (15), and Lloyd Espenschied of Bell Labs (15).

Handwritten and typed manuscript material, 1926-1966, over 200 pages, many scientific pieces with additional notes, diagrams, and calculations, as well as historical material chronicling his time with the Marconi Company, including a 21 page autobiographical sketch of his scientific career through 1926.

Miscellaneous paper and ephemera, including some photocopied material, post-1926, highlights include fine press menus for 1929 testimonial dinner given for Round by the Radio Club of America, one with signatures of over 25 guests, and a similar 1952 menu by the same organization for awarding the Armstrong Medal to Round; as well as a few scientific offprints, among clippings, photocopies, and other printed material.

Boxes 2 & 3: Thirty-Three Manuscript Scientific and Technical Notebooks.

Box 2: Scientific Notebooks, 1950s.

Numbered small notebooks, 1-21, 23, 30, each approximately with 50-150 filled in pages, mixing scientific notes with calculations and diagrams

1: 1952, 2: No date (ND), 3: ND, 4: 1954, 5: ND, 6: 1954, 7: ND, 8: ND, 9: ND, 10: ND, 11: ND, 12: ND, 13: ND, 14: ND, 15: ND, 16: ND, 17: ND, 18: 1957, 19: 1957, 20: ND, 21: ND, 23: 1959, 30: 1959

Box 3: Various Notebooks Documenting Round’s Scientific Work, 1906-1948.

Unnumbered, flip open, titled the scheme book, 1906.

Unnumbered, medium red notebook: no date.

Pulse generator: no date.

Unnumbered, medium black notebook with 4000 etched cover, 1948.

Unnumbered, small to medium red notebook, unreadable text to cover, 1958.

Unnumbered, larger black notebook, corner missing from cover: no date.

Unnumbered, larger dark red notebook, staining bottom right cover: 1941

#3, larger notebook, red, 1939.

#5, larger notebook, no date.

Unnumbered, wraps, titled power control by mechanical means, no date.

Box 4: Patents, 1908-1959; Magazines from the 1920s.

Patents: 85 printed patent specifications, some with Round's notes, 1908-1959, with additional single 1959 filled in patent form with typewritten 5 page addendum, along with small group of photocopies of Round's patents.

Magazines: 9 copies of Wireless Magazine and Amateur Wireless and Modern Wireless with articles by Round, 1927-29, some lacking covers, with rough tape repairs.

Box 5: Books, Bound Printed Material, Postcards.

Books and other bound printed material:

Postcards: circa 1900 through 1914, majority 1903-1906 from Round's trip through North America, including New England, New York, Chicago, Birmingham, Alabama, and Nova Scotia, and serving as a detailed itinerary of places visited while traveling on behalf of the Marconi Company, with some later European and Brazilian related.

48 with notes by Round, ranging from single lines to full postcards.

115 no text, most sent with postal markings. (Inventory #: List2746)