Carousel content with 1 slides.

A carousel is a rotating set of images, rotation stops on keyboard focus on carousel tab controls or hovering the mouse pointer over images. Use the tabs or the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide.

-

Slide 1:

Slide 1:

-

Slide 2: no title

Slide 2: no title -

Slide 3: no title

Slide 3: no title -

Slide 4: no title

Slide 4: no title -

Slide 5: no title

Slide 5: no title -

Slide 6: no title

Slide 6: no title -

Slide 7: no title

Slide 7: no title -

Slide 8: no title

Slide 8: no title -

Slide 9: no title

Slide 9: no title -

Slide 10: no title

Slide 10: no title -

Slide 11: no title

Slide 11: no title -

Slide 12: no title

Slide 12: no title -

Slide 13: no title

Slide 13: no title -

Slide 14: no title

Slide 14: no title -

Slide 15: no title

Slide 15: no title -

Slide 16: no title

Slide 16: no title -

Slide 17: no title

Slide 17: no title -

Slide 18: no title

Slide 18: no title -

Slide 19: no title

Slide 19: no title -

Slide 20: no title

Slide 20: no title -

Slide 21: no title

Slide 21: no title -

Slide 22: no title

Slide 22: no title -

Slide 23: no title

Slide 23: no title

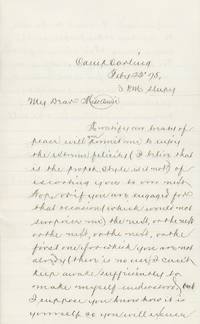

Approximately 248 total pages: 149 8.5 x 11 inches and smaller (three typed) and ninety-nine 5 x 8 inches and smaller. Most unda

1940 · California

by [Youth Culture – 1950s – Dance] Lawrence, David

California, 1940. Approximately 248 total pages: 149 8.5 x 11 inches and smaller (three typed) and ninety-nine 5 x 8 inches and smaller. Most undated; those with dates ranging from 1944 to 1958. Ninety-two pages from Nancy Gotthart and eighty-six pages from Helen Gotthart; the remaining from various friends either unsigned or with first name only. Many letters missing pages. Generally fine. David Lawrence was part of a cohort of young dancers in Southern California; he modeled and may have danced in the SoCal Ballet. His correspondents here include Nancy Gotthart, an aspiring artist and writer whom Lawrence met in a dance class; Helen Gotthart, Nancy's (truncated) mother; Leisa, a fellow aspiring dancer; Wendy, a dancer with the Players Guild; and others.

Offered here is a large lot of letters, mainly to Lawrence from friends, with those dated spanning from the mid-1940s to the late 1950s. His friends, who are mostly women, seem to be in their late teens to early twenties and are struggling to adjust to young adult life in the postwar era. Fellow dancer Leisa writes perceptively that:

"I know it is rough all over, but in a couple of years the whole world is going to see a change, and there will be a chance for the creative person to do something, that he feels he is supposed to do. I know how much I want to dance and also how much you want to dance, but to be realistic and not emotional under the conditions of the world today, we would never be able to [get] what we want." (No Date)

In the meantime, the friends are open about the emotional effects of this transitional time. Nancy Gotthart tells Lawrence that:

"I am in my little cave. It is a mess – broken glass, a couple of oil paintings torn and strewn about, my radio smashed in a sick heap by the bookcase, while various parts are scattered from one end of the apartment to the other. An empty scotch bottle reigns over the general chaos. [...] It was after I tore up the paintings, I had scratched my wrist and it was bleeding slightly – you know how it is with an animal when it scents blood: it wants more: and so did I." (October 28, 1958)

Leisa and their mutual friends are troubled as well. She writes:

"Dick, was put in an institution, because he told someone he saw God, and for 8 months, he was given nothing but shock treatments. (Please don't say anything to anyone) And I was put [in] a home for girls because I hated People, and told everyone God was going to destr[o]y them. So you see what happens to people [when] you arn't given understanding." (No Date)

Lawrence expresses a similar sentiment in an unsent response to a letter from his friend Wendy. Wendy is "working with the Players Guild, a group of dancers headed by Raoul Pausé and Marce Wild" and is starting "rehearsals for a jazy [sic] ballet in which Ron Pointdexter has done the choreography" (April 30, 1958). At that time, Lawrence was taking classes and modeling in Hollywood. In his letter to Wendy, after several missing pages, he concludes:

"[...] or anything just alone – an empty feeling of some urge of destruction – A smash-up – any one anything – the sudden desire to destroy with no attemp[t] of physical violence – this conflicting urge swells with in me like a massive wave – bound for destruction – building higher and higher – nothing can prevent it – like a tital [sic] wave it reaches its climax – then down it smashes – nothing gained – nothing lost – just a desire of self pity with no conclusion –" (November 13, 1958)

In a draft of a letter also in the archive from a Lorraine to Tom—perhaps Lorraine was a friend that Lawrence was helping to write this letter—these feelings are located squarely in the context of malaise surrounding World War II:

"As for my job, that is of no consequence. I have given notice, and this Saturday will be my last day at Gilfillan. [...] When I took the job, I went with innocent + believing eyes, thinking I was doing what I should for the war effort. I only find myself now a human parasite, wasting ½ my time doing nothing – and the most important thing expected of me is to look busy when the "big shots" go through the plant. Such waste of precious time – how I feel with you the impossible hand of army routine life crushing out all possibility of creativeness! And if one doesn't rebel inwardly (for actively it is impossible to do in your position), he falls into the rut which too many people eventually accept as part of them." (August 25, 1944)

Fortunately, Lawrence has a supportive adult in his life: Nancy's mother, Helen Gotthart, with whom Lawrence has a lengthy correspondence and an ambiguously tender relationship. Helen—who is a real estate agent and aspiring writer—encourages Lawrence to stick with dancing:

"I want to insist again that you must take at least one or two classes a week, or get into your dance clothes and give yourself a barre at the kitchen sink [...] but don't allow yourself to get stiff, whatever you do. And look like crazy for another job where you can get classes and maybe attend rehearsals again, [...] If you let things drift as they are without trying to do better in any and every way possible, then you will be as bad as R. only in a different way." (September 13, 1957)

She assures him that "if we both do our best and work as hard as we can, perhaps we will both come out on top", and promises to "do all I can to help you, or possibly I should say 'to help you help yourself,' because dance is a thing you must do for yourself" (November 10, NY).

Also of interest in the archive is Nancy's appraisal of the contemporary treatment of gay men, which they discuss several times. Nancy writes:

"Oh, yes, you made reference to some 'raids'. Were you referring to the round-up of homosexuals? There has been a great-to-do about it in the papers. Several private citizens, and, you remember Ermine Duccini? Well he was picked up. And on account of public opinions (mothers primarily) he is going to be dropped from [page missing…] turn their efforts to rounding-up dope-pushers and the like. The strange ideas & hates of the great unwashed are incomprehensible to me. I guess they feel the murders committed by the sale of heroin are less terrible. (?) Not so with me; I believe in live and let live." (May 8, 1958)

At another point, she remarks:

"As far as I am concerned what should be done with such people [i.e., gay men] is let them alone. They are as much human beings (perhaps more) as anyone else. After all, one isn't condemned because he prefers green to blue, why would one be condemned for preferring someone of one's own sex? And the thing that really gets me about all this business is that a married man can philander and make every woman he feels inclined to, while two men or two women who really love each other and don't go on the make have no rights according to our brave government. This makes me want to vomit." (No Date)

The friends' unconventional attitudes towards sexuality seem to apply to their own lives as well. Included in the archive is a very graphic break-up letter from an unknown woman to Lawrence; the fourteen-page letter is surprisingly sexually explicit, contravening stereotypes of the time:

"I have more tenderness warmth, passion, and understanding in my little finger, than most women in their whole person. Where do you think – from what well do I draw what you feel, when you think I'm being submissive? The well is bottomless, never been drained, though drank from copiously. Right now, David, I can come up with nine guys, count them, nine (of which only two have slept with me) that would come right out and say they love me! And that's only on this coast! [...] You hurt my feelings tremendously by saying that, as opposed to other women, you 'don't' like me when I'm not submissive' (!) A) When am I not submissive? Any touch from you renders me so, any indication of your desire [...]" (No Date)

Overall, an uncommon survival providing an intimate look at the inner lives of American youths coming of age after the Second World War and before the next decade's counterculture would allow them the creative freedom they desired. (Inventory #: List2749)

Offered here is a large lot of letters, mainly to Lawrence from friends, with those dated spanning from the mid-1940s to the late 1950s. His friends, who are mostly women, seem to be in their late teens to early twenties and are struggling to adjust to young adult life in the postwar era. Fellow dancer Leisa writes perceptively that:

"I know it is rough all over, but in a couple of years the whole world is going to see a change, and there will be a chance for the creative person to do something, that he feels he is supposed to do. I know how much I want to dance and also how much you want to dance, but to be realistic and not emotional under the conditions of the world today, we would never be able to [get] what we want." (No Date)

In the meantime, the friends are open about the emotional effects of this transitional time. Nancy Gotthart tells Lawrence that:

"I am in my little cave. It is a mess – broken glass, a couple of oil paintings torn and strewn about, my radio smashed in a sick heap by the bookcase, while various parts are scattered from one end of the apartment to the other. An empty scotch bottle reigns over the general chaos. [...] It was after I tore up the paintings, I had scratched my wrist and it was bleeding slightly – you know how it is with an animal when it scents blood: it wants more: and so did I." (October 28, 1958)

Leisa and their mutual friends are troubled as well. She writes:

"Dick, was put in an institution, because he told someone he saw God, and for 8 months, he was given nothing but shock treatments. (Please don't say anything to anyone) And I was put [in] a home for girls because I hated People, and told everyone God was going to destr[o]y them. So you see what happens to people [when] you arn't given understanding." (No Date)

Lawrence expresses a similar sentiment in an unsent response to a letter from his friend Wendy. Wendy is "working with the Players Guild, a group of dancers headed by Raoul Pausé and Marce Wild" and is starting "rehearsals for a jazy [sic] ballet in which Ron Pointdexter has done the choreography" (April 30, 1958). At that time, Lawrence was taking classes and modeling in Hollywood. In his letter to Wendy, after several missing pages, he concludes:

"[...] or anything just alone – an empty feeling of some urge of destruction – A smash-up – any one anything – the sudden desire to destroy with no attemp[t] of physical violence – this conflicting urge swells with in me like a massive wave – bound for destruction – building higher and higher – nothing can prevent it – like a tital [sic] wave it reaches its climax – then down it smashes – nothing gained – nothing lost – just a desire of self pity with no conclusion –" (November 13, 1958)

In a draft of a letter also in the archive from a Lorraine to Tom—perhaps Lorraine was a friend that Lawrence was helping to write this letter—these feelings are located squarely in the context of malaise surrounding World War II:

"As for my job, that is of no consequence. I have given notice, and this Saturday will be my last day at Gilfillan. [...] When I took the job, I went with innocent + believing eyes, thinking I was doing what I should for the war effort. I only find myself now a human parasite, wasting ½ my time doing nothing – and the most important thing expected of me is to look busy when the "big shots" go through the plant. Such waste of precious time – how I feel with you the impossible hand of army routine life crushing out all possibility of creativeness! And if one doesn't rebel inwardly (for actively it is impossible to do in your position), he falls into the rut which too many people eventually accept as part of them." (August 25, 1944)

Fortunately, Lawrence has a supportive adult in his life: Nancy's mother, Helen Gotthart, with whom Lawrence has a lengthy correspondence and an ambiguously tender relationship. Helen—who is a real estate agent and aspiring writer—encourages Lawrence to stick with dancing:

"I want to insist again that you must take at least one or two classes a week, or get into your dance clothes and give yourself a barre at the kitchen sink [...] but don't allow yourself to get stiff, whatever you do. And look like crazy for another job where you can get classes and maybe attend rehearsals again, [...] If you let things drift as they are without trying to do better in any and every way possible, then you will be as bad as R. only in a different way." (September 13, 1957)

She assures him that "if we both do our best and work as hard as we can, perhaps we will both come out on top", and promises to "do all I can to help you, or possibly I should say 'to help you help yourself,' because dance is a thing you must do for yourself" (November 10, NY).

Also of interest in the archive is Nancy's appraisal of the contemporary treatment of gay men, which they discuss several times. Nancy writes:

"Oh, yes, you made reference to some 'raids'. Were you referring to the round-up of homosexuals? There has been a great-to-do about it in the papers. Several private citizens, and, you remember Ermine Duccini? Well he was picked up. And on account of public opinions (mothers primarily) he is going to be dropped from [page missing…] turn their efforts to rounding-up dope-pushers and the like. The strange ideas & hates of the great unwashed are incomprehensible to me. I guess they feel the murders committed by the sale of heroin are less terrible. (?) Not so with me; I believe in live and let live." (May 8, 1958)

At another point, she remarks:

"As far as I am concerned what should be done with such people [i.e., gay men] is let them alone. They are as much human beings (perhaps more) as anyone else. After all, one isn't condemned because he prefers green to blue, why would one be condemned for preferring someone of one's own sex? And the thing that really gets me about all this business is that a married man can philander and make every woman he feels inclined to, while two men or two women who really love each other and don't go on the make have no rights according to our brave government. This makes me want to vomit." (No Date)

The friends' unconventional attitudes towards sexuality seem to apply to their own lives as well. Included in the archive is a very graphic break-up letter from an unknown woman to Lawrence; the fourteen-page letter is surprisingly sexually explicit, contravening stereotypes of the time:

"I have more tenderness warmth, passion, and understanding in my little finger, than most women in their whole person. Where do you think – from what well do I draw what you feel, when you think I'm being submissive? The well is bottomless, never been drained, though drank from copiously. Right now, David, I can come up with nine guys, count them, nine (of which only two have slept with me) that would come right out and say they love me! And that's only on this coast! [...] You hurt my feelings tremendously by saying that, as opposed to other women, you 'don't' like me when I'm not submissive' (!) A) When am I not submissive? Any touch from you renders me so, any indication of your desire [...]" (No Date)

Overall, an uncommon survival providing an intimate look at the inner lives of American youths coming of age after the Second World War and before the next decade's counterculture would allow them the creative freedom they desired. (Inventory #: List2749)