TRAVEL IN JAPAN - From 17th to the 20th Century

It is simple-minded perhaps to propose the example of Japanese tourists from the recent past as a proof of the cultural importance of travel in traditional Japan...

KODOMO NO KUNI - The Land of Children

The finest children's magazine of the prewar period in Japan. Amazingly long-lived, it was published monthly from 1922 to 1944

Hokusai and His School

A few books by Hokusai and his followers... Not the rare and beautiful illustrated poetry anthologies of his early and middle years, when he was an up and coming artist working with Tsutaya and other deluxe printing houses. Rather these are the books from his later years that were so immensely popular it is very hard to find early acceptable printings of them.

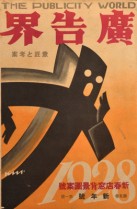

20th Century Japan

Japanese Art and Photography in the 20th Century- Art Nouveau, Avant garde, and more..

EHON- JAPANESE PICTURE BOOKS

What follows is a list of traditional Japanese ehon 絵本. Simply put, ehon are “picture books.” The term embraces many different approaches to book illustration, from those works that are primarily textual and simply enlivened by plates, to works that are really printed gachō 画帳 or gafu 画譜.

The term embraces many different approaches to book illustration, from those works that are primarily textual and simply enlivened by plates, to works that are really printed gachō 画帳 or gafu 画譜.

In gafu, or albums of illustrations, the arrangement of images is a matter of creation, rather than serendipity. An effort not to have the pictures elucidate an explicit or implicit narrative, like a comic book or graphic novel with or without text, but rather to touch the aesthetic and emotional in such a way as to listen to the images talking to each other as you move through the book. Think of a gafu or the like as being similar to a contemporary photobook. Not so much a question of narrative as of something much deeper, a shared bond between the artist and viewer.

In this list we have put together a group of works that are largely from early modern Japan. During that period of a burgeoning economy, the primacy of the woodblock print was such that an enormous body of skillfully drawn, carved and printed works flooded the marketplace. The reason we call Edo Japan (1603-1868) the “early modern era” is that the seeds of the cultural and economic revolution of the late 19th century, that continues to the present, were sown quite early on in the 17th century.

It is no accident that the evolution of class structure, culture, and mores in the 17th century was accompanied by the rise of a new aesthetic of artistic reproduction, where high and low culture mingled. The handpainted story books, known as Nara ehon 奈良絵本, so popular with the old nobility and the rising military class, were supplemented by the printed ehon. At first the printed ehon imitated earlier, more highbrow works, (as for example the early 17th century deluxe, printed and illustrated editions of the iconic TALES OF ISE) Soon, however, books were down in the trenches - in the demi-monde and the quotidian realities of big city life, as engraved on wood by hundreds of publisher/printers. Common folk, poor and some increasingly wealthy, wanted to see themselves within the pages; to read about their own daily exploits. They wanted to learn and share the 1000 year old culture they inherited, and often they wanted to satirise it, as well.

So these are picture books, some are text with pictures, some pictures with a bit of text or even no text at all. Some are commercially published, others were created to showcase the work of a whole group of artists and litterateurs, including poetry contests, and the like. Then there were “meishoki” 名所記: early guidebooks dedicated to local history and views, for those with an interest in travel in a world where travel was unusual. There were albums of paintings rendered in woodblock, etiquette guides, erotica; nothing that could be expressed was safe from illustration.

The term embraces many different approaches to book illustration, from those works that are primarily textual and simply enlivened by plates, to works that are really printed gachō 画帳 or gafu 画譜.

In gafu, or albums of illustrations, the arrangement of images is a matter of creation, rather than serendipity. An effort not to have the pictures elucidate an explicit or implicit narrative, like a comic book or graphic novel with or without text, but rather to touch the aesthetic and emotional in such a way as to listen to the images talking to each other as you move through the book. Think of a gafu or the like as being similar to a contemporary photobook. Not so much a question of narrative as of something much deeper, a shared bond between the artist and viewer.

In this list we have put together a group of works that are largely from early modern Japan. During that period of a burgeoning economy, the primacy of the woodblock print was such that an enormous body of skillfully drawn, carved and printed works flooded the marketplace. The reason we call Edo Japan (1603-1868) the “early modern era” is that the seeds of the cultural and economic revolution of the late 19th century, that continues to the present, were sown quite early on in the 17th century.

It is no accident that the evolution of class structure, culture, and mores in the 17th century was accompanied by the rise of a new aesthetic of artistic reproduction, where high and low culture mingled. The handpainted story books, known as Nara ehon 奈良絵本, so popular with the old nobility and the rising military class, were supplemented by the printed ehon. At first the printed ehon imitated earlier, more highbrow works, (as for example the early 17th century deluxe, printed and illustrated editions of the iconic TALES OF ISE) Soon, however, books were down in the trenches - in the demi-monde and the quotidian realities of big city life, as engraved on wood by hundreds of publisher/printers. Common folk, poor and some increasingly wealthy, wanted to see themselves within the pages; to read about their own daily exploits. They wanted to learn and share the 1000 year old culture they inherited, and often they wanted to satirise it, as well.

So these are picture books, some are text with pictures, some pictures with a bit of text or even no text at all. Some are commercially published, others were created to showcase the work of a whole group of artists and litterateurs, including poetry contests, and the like. Then there were “meishoki” 名所記: early guidebooks dedicated to local history and views, for those with an interest in travel in a world where travel was unusual. There were albums of paintings rendered in woodblock, etiquette guides, erotica; nothing that could be expressed was safe from illustration.

KATAZOME- Stencil-Printed Books

Katazome, the use of a stencil as part of a process of paper and cloth dyeing, traces its roots, as do so many arts and crafts in East Asia, to the "Middle Kingdom" - China.

Here, we are concerned with its appearance and employment in Japan. Early on, during the Nara period (late 8th century), the stencils themselves appear to have been carved from wood. Examples remain at Hōryūji Temple, etc. But, eventually, paper became the preferred tool for stencilling.

The use of stencils and takuhon rubbings may well be older than the employment of carved wood block hangi to create prints, books and reproductions. Indeed, much later, the earliest color-printed works in both China and Japan in the 17th and 18th century often were colored mostly using stencilling techniques.

So, it is delightful to find wonderful examples of brightly colored, mingei folk art-inspired, katazome stencil-printed books still being created in the recent past in Japan. Often inspired by folk stencilling like the remarkable bingata patterning of Okinawa, they created a new aesthetic world in the latter half of the 20th century.

Such artists and scholars of dyeing techniques as Gotō, Serizawa, Kamakura, Okamura, Kanzaki and others employed katazome to produce wonderful prints and artist's books, which were issued by such publishers as Gohachi Shobō in Tōkyō. Artists famous in other media, like Sekino Junichirō, also experimented with katazome and produced masterpieces of the genre.

We are presenting here a small list of works, mostly done in that post-War period, which include some of the most significant productions in the medium.

You might also note that we have virtually the entire "toolset" of hand-cut katagami paper, many thousands of them, from the remains of a Kyōto dyeing house. It makes a fascinating and illustrative record of technique and product from the world of traditional Japanese design and textile dyeing.

Please enjoy the descriptions below, and don't forget to click on the thumbnail images to see selections from the works. There are treasures within!

Here, we are concerned with its appearance and employment in Japan. Early on, during the Nara period (late 8th century), the stencils themselves appear to have been carved from wood. Examples remain at Hōryūji Temple, etc. But, eventually, paper became the preferred tool for stencilling.

The use of stencils and takuhon rubbings may well be older than the employment of carved wood block hangi to create prints, books and reproductions. Indeed, much later, the earliest color-printed works in both China and Japan in the 17th and 18th century often were colored mostly using stencilling techniques.

So, it is delightful to find wonderful examples of brightly colored, mingei folk art-inspired, katazome stencil-printed books still being created in the recent past in Japan. Often inspired by folk stencilling like the remarkable bingata patterning of Okinawa, they created a new aesthetic world in the latter half of the 20th century.

Such artists and scholars of dyeing techniques as Gotō, Serizawa, Kamakura, Okamura, Kanzaki and others employed katazome to produce wonderful prints and artist's books, which were issued by such publishers as Gohachi Shobō in Tōkyō. Artists famous in other media, like Sekino Junichirō, also experimented with katazome and produced masterpieces of the genre.

We are presenting here a small list of works, mostly done in that post-War period, which include some of the most significant productions in the medium.

You might also note that we have virtually the entire "toolset" of hand-cut katagami paper, many thousands of them, from the remains of a Kyōto dyeing house. It makes a fascinating and illustrative record of technique and product from the world of traditional Japanese design and textile dyeing.

Please enjoy the descriptions below, and don't forget to click on the thumbnail images to see selections from the works. There are treasures within!

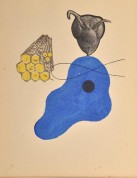

Kōshirō Onchi

The accomplishments of Onchi Kōshirō 恩地孝四郎 (1891–1955) throughout the first half of the 20th century extend far beyond his eminence as a printmaker. He was an innovator who domesticated the ideas and ideals of abstraction and "creative printmaking" in Japan when still in art school. He was also an oil painter, largely in his early years, where he experimented with themes and concepts he would also apply to his prints.

From his early years, working with Takehisa Yumeiji 竹久夢二, among others, he began a long career as a book designer and book illustrator. From the very beginning of his life in the arts he was the center and focus of the Creative Print movement, surrounding himself with fellow artists who took inspiration from his dedication to the cause of self-expression. From his student efforts in the nineteen-teens creating the amazing TSUKUHAE journal until his premature and much-mourned death in the 50s, he was a dominant influence in his world.

He was also a poet and photographer of no mean skill. He combined all those interests in the wonderful artist's books he created, such masterworks as UMI NO DOWA, KISETSU-HYŌ, HIKKO KANNO, among many others. He was editor of the most important book arts periodical of the pre-War period, SHOSŌ magazine. He designed over a thousand books, collaborated in his later years with such important figures as Kitasono Katue - in short, he was the major figure involved with works on paper in his time and provided support and inspiration to scores of other artists.

It has been decades since the wonderful work on Onchi done by Elizabeth Swinton, THE GRAPHIC ART OF ONCHI KOSHIRO; INNOVATION AND TRADITION, the only substantial work on him ever written in English. Though he is the subject of a small cottage industry of scholarship in Japan, he is largely a much-admired mystery abroad in the 21st century.

So, we thought it might be fun to put together a smattering of interesting material by him that covers the breadth of his interests: sketches, illustrations, artist's books, his book of photography, one of the products in book form of the wartime Thursday Group, 4 amazing and rare oil paintings, several books designed by him, and a run of SHOSŌ magazine. The list goes on. But have a look and see for yourself.

There are treasures herein.

From his early years, working with Takehisa Yumeiji 竹久夢二, among others, he began a long career as a book designer and book illustrator. From the very beginning of his life in the arts he was the center and focus of the Creative Print movement, surrounding himself with fellow artists who took inspiration from his dedication to the cause of self-expression. From his student efforts in the nineteen-teens creating the amazing TSUKUHAE journal until his premature and much-mourned death in the 50s, he was a dominant influence in his world.

He was also a poet and photographer of no mean skill. He combined all those interests in the wonderful artist's books he created, such masterworks as UMI NO DOWA, KISETSU-HYŌ, HIKKO KANNO, among many others. He was editor of the most important book arts periodical of the pre-War period, SHOSŌ magazine. He designed over a thousand books, collaborated in his later years with such important figures as Kitasono Katue - in short, he was the major figure involved with works on paper in his time and provided support and inspiration to scores of other artists.

It has been decades since the wonderful work on Onchi done by Elizabeth Swinton, THE GRAPHIC ART OF ONCHI KOSHIRO; INNOVATION AND TRADITION, the only substantial work on him ever written in English. Though he is the subject of a small cottage industry of scholarship in Japan, he is largely a much-admired mystery abroad in the 21st century.

So, we thought it might be fun to put together a smattering of interesting material by him that covers the breadth of his interests: sketches, illustrations, artist's books, his book of photography, one of the products in book form of the wartime Thursday Group, 4 amazing and rare oil paintings, several books designed by him, and a run of SHOSŌ magazine. The list goes on. But have a look and see for yourself.

There are treasures herein.

AVANT-GARDE (Japan and East Asia)

The avant garde in Japan has been evolving for over a century. In many ways, given the historical timing, the recognition and adaptation of Western art techniques after the opening of Japan merged quite seamlessly with the introduction of avant garde impulses internationally. Cezanne followed soon after the introduction of oil painting, itself, in the Japanese cultural imagination. It was all new. But Japanese sophistication grew quickly. And, given the freedom promised by the new schools, the Japanese artist was thereby given the opportunity to experiment, to recreate and adapt, to express a personal vision using the new tools at hand.

Futurism, Surrealism, Dada, Expressionism - all were given free play, internalized and recreated in such schools or movements as MAVO, Mirai-ha, etc. and, after the war, Gutai.

The question of influence is always implied.... Were the Japanese simply "copying" (whatever that might mean)? A look through the productions of that time reveals influence, of course, but research makes it quite clear that in many ways, the influence was mutual.

Futurism, Surrealism, Dada, Expressionism - all were given free play, internalized and recreated in such schools or movements as MAVO, Mirai-ha, etc. and, after the war, Gutai.

The question of influence is always implied.... Were the Japanese simply "copying" (whatever that might mean)? A look through the productions of that time reveals influence, of course, but research makes it quite clear that in many ways, the influence was mutual.

CATALOGUE 64A: Japan and East Asia

NEW ARRIVALS

CATALOGUE 63A: Japan and East Asia

A list of new arrivals and recent acquisitions.

Contact the Seller

705 Centre St.

Contact the Seller

705 Centre St.

Boston, MA 02130

Share this Profile