1732 · Salamanca

by THESIS PRINT ON SILK

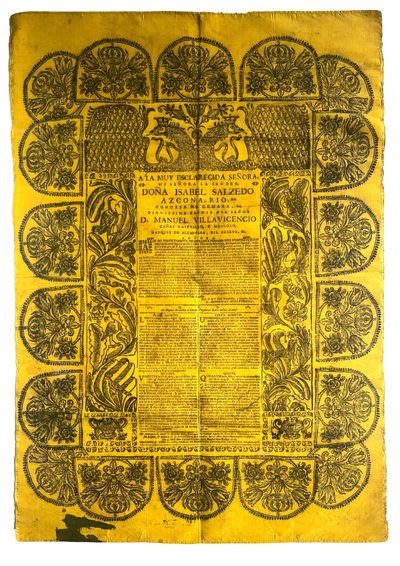

Salamanca: Eugenio Garcia de Honorato, 1732. Large folio broadside (817 x 520 mm.), printed on yellow satin silk, the letterpress text, partly in two columns, printed at center within a large double woodcut border, the outer border composed of 14 stamped impressions of a single ornamental woodblock and 4 impressions of a corner block, the inner border composed of five woodcuts printed from four blocks: two different vertical blocks forming lateral bands of scrolling foliage with birds and exotic animals; at top the bicephalous imperial eagle with giant stylized wings, a flower between the two heads at top, and a small vase block repeated at the lower (truncated) corners; type ornaments separating the blocks. Upper and lower edges tucked and stitched. Fine condition (a couple of small old wax stains to text, ink stain and one other small trace of staining in lower margin, not affecting printed area). ***

A broadside summary and announcement of a thesis defense on a theological subject, luxuriously printed on yellow silk. The lengthy dedication, in Spanish, to a prominent female aristocrat, the Countess of Gomara, wife of Manuel de Villavicencio y Castrillo, fourth Marquis of Alcántara del Cuervo, is signed by D. Antonio di Mora Thenorio, the presiding professor (praeses). The student Francisco Lorenzo Serrano’s public thesis defense, on the (puzzling) question “An Magnus Bernardus à Christo, Virgine ve Maria melleus dicatur” (Whether Saint Bernard was called sweet [or spoken of sweetly] by Christ, the Virgin, or Mary[?]), was to be held in the great hall (the “greatest of the world,”) of the University of Salamanca, between 8 and 10 am on 11 May 1732.

This bold and eye-catching silk broadside testifies to a vanished aspect of early modern university life. Not only were theses defended publicly, but these defenses were social occasions, often entailing lavish celebrations, which could extend into the night. Broadside thesis summaries such as this one were posted on the walls and also paraded around the town along with the student. The two small wax stains on this example may be evidence of a candlelit procession or party (this was pointed out by Suzanne Karr Schmidt in her discussion of a particularly luxurious Mexican thesis print on silk, which also has some wax stains, held by the Newberry library). These announcements and festivities were paid for at least in part by the students’ families. The former took their most prestigious form in copies printed on silk, a tradition dating back, in France and perhaps also in Spain, to the seventeenth century (see Delmas).

“In early modern institutions of higher education, academic dissertations to be defended in public were published in the form of decorated broadsheets summarising the student’s conclusions. The first aim of these engraved posters was to advertise the disputation and to provide an overview of the themes [called theses or conclusions] to be discussed. They also presented a visual programme of its unfolding, and could be kept as a souvenir after the ceremony. [Having originated in Jesuit colleges,] this practice was common mostly in the Catholic countries: Italy, France, Southern Netherlands, Germanic countries and Austria.... Thesis defences, or disputations, were used as exams to conclude academic studies of master or doctorate, and to demonstrate the student’s graduation. Pro gradu disputations were of great significance within the academic system. They were subject to rigorous etiquette and important pageantry dictated by the educational establishments. Illustrious guests, chamber orchestras, processions through the town and banquets turned them into social events. The institutions organised the festivities ... Such ceremonies were very expensive, because they included the printing of the thesis posters, the decoration of the college hall and the organisation of a dinner for the audience. Therefore, only wealthy men could afford this, while the others just took the regular exams...” (De Muelenaere, “Images,” pp. 49-50).

The unusual dedication in this broadside from the praeses to an aristocratic patroness may indicate that she played a role in supporting the institution. The University of Salamanca, the oldest and most respected university in Spain, would have attracted aristocratic patrons from all over the realm. The Counts of Gómara, the family of Isabel de Salcedo y Rio, were from Soria, about 300 km east of Salamanca.

While the French produced elaborately engraved figurative thesis prints (which they called simply theses, a word applied also to the public defenses), the traditional Spanish presentation of these broadsides, also found in Mexican examples*, was to enclose the text in woodcut ornamental borders. It was apparently common to stamp single repeated woodblocks to create the borders, rather than printing them from multiple blocks locked into the forme with the type. In the present example the outer border is built up from a repeated ornamental block showing a crown and fleur-de-lis set between flowers; the four corner blocks are cut-down versions of the same ornament, which appear to be overlapped by the main border. It is possible that the printer reserved such large decorative woodblocks specifically for the production of thesis prints, which may have consituted a not inconsiderable segment of his output: the Salamanca family of printers García de Honorato, active from 1680 to 1770, were royal printers who often published tracts for the University.

The print-runs of broadsides such as this, and the relation between paper copies, if there were any, to copies on silk, are difficult to ascertain. The stamping of the woodblocks would seem to indicate production of only a limited number of copies. Perhaps this practice was related to the challenges of printing on textile, which would imply that these broadsides were only produced on silk. I locate no record of this thesis print, although such ephemeral broadsides have often slipped through the cracks of library cataloguing.

Not in OCLC, REBIUN, the CCPB, or KVK. Cf. G. de Mûelenaere, Early modern thesis prints in the Southern Netherlands (Leiden: Brill, 2022); de Mûelenaere, “Images of the Courtier in Flemish Thesis Prints (17th-18th centuries)” Paper presented at the Renaissance Society of America Conference in Berlin, 26-28 March 2015, Ghent University Academic Bibliography (GEMCA): Papers in Progress 2017 vol. 4, no.1 (online), pp. 49-62; J-F. Delmas, “Estampes et textes imprimés sur tissus de soie. Catalogue raisonné de thèses et d'exercices publics XVIIe-XIXe siècles,” Bulletin du bibliophile, 2005, no. 1, pp. 85-142. See S. Karr-Schmidt’s presentation of a 1746 Mexican thesis print at the symposium “Global Impressions: Printing on Fabric in the Early Modern World,” Oct. 22 2024, Newberry Center for Renaissance Studies (on YouTube). For information on the earlier history of thesis broadsides, see Saskia Limbach, “Advertising Medical Studies in Sixteenth-Century Basel: Function and Use of Academic Disputations,” in Pettegree, ed., Broadsheets: Single-Sheet Publications in the First Age of Print (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 376-398.

* See, for example, a Mexican thesis print in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the aforementioned Newberry example. (Inventory #: 4427)

A broadside summary and announcement of a thesis defense on a theological subject, luxuriously printed on yellow silk. The lengthy dedication, in Spanish, to a prominent female aristocrat, the Countess of Gomara, wife of Manuel de Villavicencio y Castrillo, fourth Marquis of Alcántara del Cuervo, is signed by D. Antonio di Mora Thenorio, the presiding professor (praeses). The student Francisco Lorenzo Serrano’s public thesis defense, on the (puzzling) question “An Magnus Bernardus à Christo, Virgine ve Maria melleus dicatur” (Whether Saint Bernard was called sweet [or spoken of sweetly] by Christ, the Virgin, or Mary[?]), was to be held in the great hall (the “greatest of the world,”) of the University of Salamanca, between 8 and 10 am on 11 May 1732.

This bold and eye-catching silk broadside testifies to a vanished aspect of early modern university life. Not only were theses defended publicly, but these defenses were social occasions, often entailing lavish celebrations, which could extend into the night. Broadside thesis summaries such as this one were posted on the walls and also paraded around the town along with the student. The two small wax stains on this example may be evidence of a candlelit procession or party (this was pointed out by Suzanne Karr Schmidt in her discussion of a particularly luxurious Mexican thesis print on silk, which also has some wax stains, held by the Newberry library). These announcements and festivities were paid for at least in part by the students’ families. The former took their most prestigious form in copies printed on silk, a tradition dating back, in France and perhaps also in Spain, to the seventeenth century (see Delmas).

“In early modern institutions of higher education, academic dissertations to be defended in public were published in the form of decorated broadsheets summarising the student’s conclusions. The first aim of these engraved posters was to advertise the disputation and to provide an overview of the themes [called theses or conclusions] to be discussed. They also presented a visual programme of its unfolding, and could be kept as a souvenir after the ceremony. [Having originated in Jesuit colleges,] this practice was common mostly in the Catholic countries: Italy, France, Southern Netherlands, Germanic countries and Austria.... Thesis defences, or disputations, were used as exams to conclude academic studies of master or doctorate, and to demonstrate the student’s graduation. Pro gradu disputations were of great significance within the academic system. They were subject to rigorous etiquette and important pageantry dictated by the educational establishments. Illustrious guests, chamber orchestras, processions through the town and banquets turned them into social events. The institutions organised the festivities ... Such ceremonies were very expensive, because they included the printing of the thesis posters, the decoration of the college hall and the organisation of a dinner for the audience. Therefore, only wealthy men could afford this, while the others just took the regular exams...” (De Muelenaere, “Images,” pp. 49-50).

The unusual dedication in this broadside from the praeses to an aristocratic patroness may indicate that she played a role in supporting the institution. The University of Salamanca, the oldest and most respected university in Spain, would have attracted aristocratic patrons from all over the realm. The Counts of Gómara, the family of Isabel de Salcedo y Rio, were from Soria, about 300 km east of Salamanca.

While the French produced elaborately engraved figurative thesis prints (which they called simply theses, a word applied also to the public defenses), the traditional Spanish presentation of these broadsides, also found in Mexican examples*, was to enclose the text in woodcut ornamental borders. It was apparently common to stamp single repeated woodblocks to create the borders, rather than printing them from multiple blocks locked into the forme with the type. In the present example the outer border is built up from a repeated ornamental block showing a crown and fleur-de-lis set between flowers; the four corner blocks are cut-down versions of the same ornament, which appear to be overlapped by the main border. It is possible that the printer reserved such large decorative woodblocks specifically for the production of thesis prints, which may have consituted a not inconsiderable segment of his output: the Salamanca family of printers García de Honorato, active from 1680 to 1770, were royal printers who often published tracts for the University.

The print-runs of broadsides such as this, and the relation between paper copies, if there were any, to copies on silk, are difficult to ascertain. The stamping of the woodblocks would seem to indicate production of only a limited number of copies. Perhaps this practice was related to the challenges of printing on textile, which would imply that these broadsides were only produced on silk. I locate no record of this thesis print, although such ephemeral broadsides have often slipped through the cracks of library cataloguing.

Not in OCLC, REBIUN, the CCPB, or KVK. Cf. G. de Mûelenaere, Early modern thesis prints in the Southern Netherlands (Leiden: Brill, 2022); de Mûelenaere, “Images of the Courtier in Flemish Thesis Prints (17th-18th centuries)” Paper presented at the Renaissance Society of America Conference in Berlin, 26-28 March 2015, Ghent University Academic Bibliography (GEMCA): Papers in Progress 2017 vol. 4, no.1 (online), pp. 49-62; J-F. Delmas, “Estampes et textes imprimés sur tissus de soie. Catalogue raisonné de thèses et d'exercices publics XVIIe-XIXe siècles,” Bulletin du bibliophile, 2005, no. 1, pp. 85-142. See S. Karr-Schmidt’s presentation of a 1746 Mexican thesis print at the symposium “Global Impressions: Printing on Fabric in the Early Modern World,” Oct. 22 2024, Newberry Center for Renaissance Studies (on YouTube). For information on the earlier history of thesis broadsides, see Saskia Limbach, “Advertising Medical Studies in Sixteenth-Century Basel: Function and Use of Academic Disputations,” in Pettegree, ed., Broadsheets: Single-Sheet Publications in the First Age of Print (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 376-398.

* See, for example, a Mexican thesis print in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the aforementioned Newberry example. (Inventory #: 4427)