Carousel content with 1 slides.

A carousel is a rotating set of images, rotation stops on keyboard focus on carousel tab controls or hovering the mouse pointer over images. Use the tabs or the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide.

Hardcover

1525 · [Erfurt]

by Müntzer, Thomas (1489-1525); Luther, Martin (1483-1546)

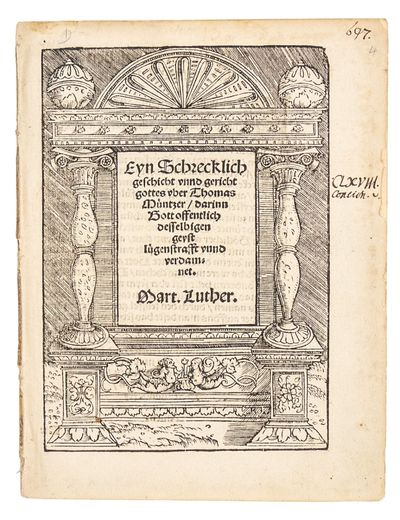

[Erfurt]: [Melchior Sachse], 1525. SECOND EDITION (in the year of the 1st ed.). Hardcover. Fine. Stitched. Housed in a modern clamshell box. A very good copy of this scarce publication. Very slight curling to extreme upper and outer margin of title, title lightly toned at head. Very light marginal stain on penultimate leaf. Early foliation in upper corners. Blank verso of final leaf with mild soiling. With an elaborated woodcut title-page border (Luther, Titeleinfassungen der Reformationszeit, 74). Both Claus (who lists eleven printings) and Benzing (who lists ten) place this second. A rare collection of four letters by the radical reformer Thomas Müntzer, (truncated) the “murderous and bloodthirsty prophet” and the most significant figure in the second, crucial phase of the Peasants’ War (Bauernkrieg), one of the bloodiest chapters in the turbulent early history of the German Reformation, which left over 100,000 dead. These letters were published by Martin Luther to expose his former ally’s most heretical and radical ideas.

In 1523, Müntzer, formerly the leader of the radical “Zwickau Prophets” began to radicalize the area of Allstedt, where he was then pastor, preaching that the ungodly were to be eliminated and the elect would establish a kingdom of Christ on earth and threatening the political rulers of the area with rebellion. In early 1524, as Müntzer grew bolder in his denunciation of the authorities and called for an elimination of the enemies of God, he divided the citizenry into military units in order to resist any outside interference in his activities. Müntzer openly challenged and attacked Luther, who was openly opposed to Müntzer’s ministry of the elect, as one of “our mad, debauching pigs, which are horrified by the windstorm, the raging billows and by all the waters of wisdom.”

In his commentary that accompanies the letters, Luther writes, “I write all of this and will have it printed not because I am joyful at the misfortunes of others . . . I only really want to warn all other rebels that they should avoid suffering from the same judgement and anger of God, and should turn away from the harmful false prophets and give themselves up to peace and obedience.” Following Müntzer’s execution on May 27, Luther would write “I killed Müntzer; his death is on my shoulders. But I did it because he wanted to kill my Christ’”. (Brecht Vol II, p. 185)

In these letters Müntzer claims he receives orders from God, threatens to murder aristocrats (calling one a “sack of maggots”), refers to Luther’s theology as “Martin’s peasant gruel”, names the leaders of the Allstedt uprising (see below), and provides updates on peasant revolts in other towns.

The letters were written in April and May 1525, during the Peasants’ War, in the three weeks leading up to the disastrous Battle of Frankenhausen on May 15, in which 5,000 peasants died. Muntzer was captured during the battle and imprisoned, and soon after executed. Luther published this book following Müntzer's execution, a punishment Luther claims was God’s judgement on the rebellion: “You can see how this murderous spirit boasted that God spoke with him and that he fulfilled the will of God and acted as if he would gain everything. And yet, before he could turn around, he lay there with several thousand others in the mud.”

The first letter Luther prints is Müntzer’s letter to the people of Allstedt, written April 26 or 27, in which he tells the people that they must be prepared to suffer for God: “May the pure fear of God be with you, dear brothers. How much longer will you sleep, how much longer will you resist God’s Will . . . if you are not willing to suffer for the sake of God, then you will become martyrs of the Devil.”

Müntzer describes recent successes in the Peasants’ War: “In Fulda in Easter week, four abbeys were laid waste, the peasants of Klettgau and Hegau in the Black Forest have risen, three times one hundred thousand strong, and the army is growing ever greater” and “the people (of Salza) wanted to lay hands on the administrator of Duke Georg because he had secretly wanted to kill three of them.”

Müntzer exhorts the people of Allstedt to take up arms against the nobles: “On, on, onwards, for the fire is hot!”, and he names four men to lead the uprising in Allstedt: “You must set to it, onwards, for it is time. Let Balthasar and Barthel Krump, Valentin and Bischoff lead the dance”.

The second letter is to Müntzer’s “arch-enemy”, Count Ernst of Mansfeld, written on May 12. It was at Ernst’s Heldrungen Castle that Müntzer was tortured following his capture at the Battle of Frankenhausen (May 15.)

Müntzer enumerates the Count’s crimes, including “tyrannical raging”, martyring Christians, and slandering Christianity. He asks the Count, “you miserable, wretched sack of maggots – who made you into a prince over the people whom God redeemed with his own precious blood?”

Count Ernst is promised “safe-conduct” if he repents, but if he refuses “every brother will be prepared to spill their own blood to fight you, as if you were the Turk. Then you will be hunted down and rooted out, for every man will be far keener to gain an indulgence at your expense than any indulgence that the Pope ever offered.”

Müntzer claims to be an instrument of God in destroying the unrepentant Ernst: “we have been given our orders, I say this to you: the eternal living God has commanded that you be cast down from your throne by the power that has been given to us.”

In the third letter, to Albrecht (or Albert) von Mansfeld, Müntzer asks “Have you not been able to spoon up from your Lutheran gruel, your Wittenberg soup, that which Ezekiel prophesied in his 37th chapter? And have you not been able to taste in your Martin’s peasant gruel . . . that God would command all the birds of the air to feast on the flesh of the princes and commanded the unthinking beasts to lap up the blood of the bigwigs, as is described in the secret book of revelations?”

The following day Müntzer again writes to Albrecht in the fourth letter, suggesting a parley between the peasants and the aristocracy: “We invite you and your men to a Christian meeting, with around thirty horsemen, to appear at Mertens Rita just before the bridge, at twelve o’clock tomorrow, Friday.” Instead of a negotiation, the Battle of Frankenhausen took place.

In his commentary on the letters, Luther describes Müntzer’s most fantastical claims: “the peasants could strike five dead with nothing but a felt hat”, “the bullets would turn back in flight and slay the enemy”, and Müntzer’s sleeve would “catch all the bullets which were fired against his people.”

The Peasants’ War was one of the bloodiest chapters in the turbulent early history of the German Reformation. The uprising began in upper Swabia in early 1524 and quickly spread to southern and western Germany, as well as to parts of Switzerland and Austria. The peasants were motivated by a number of factors: crushing taxation, lack of a voice in government, no recourse to the courts, crop failure, and helplessness in the face of their feudal masters’ demands. But whereas these conditions had resulted in smaller uprisings in the past, the massive rebellion of 1524-5 was also a result of the turbulent upheaval caused by the nascent Reformation. By the time the rebellion was crushed in late 1525, some 100,000 combatants and civilians had been killed. Reprisals were carried out for the next two years, and the peasants’ demands, as outlined in their Twelve Articles, came to nothing.

Three of the letters Luther included in this pamphlet are in “The Collected Works of Thomas Müntzer” (Matheson, 1994), they are numbers 75 - “To the People of Allstedt” (composed April 26 or 27), 88 - “To Count Ernst of Mansfeld” and 89 - “To Count Albert von Mansfeld” (both composed on May 12). The fourth letter is also to Count Albert, composed on May 13. All are from 1525. The translation is by Andrew Drummond, author of “The Dreadful History and Judgment of God on Thomas Müntzer” (2024). (Inventory #: 5149)

In 1523, Müntzer, formerly the leader of the radical “Zwickau Prophets” began to radicalize the area of Allstedt, where he was then pastor, preaching that the ungodly were to be eliminated and the elect would establish a kingdom of Christ on earth and threatening the political rulers of the area with rebellion. In early 1524, as Müntzer grew bolder in his denunciation of the authorities and called for an elimination of the enemies of God, he divided the citizenry into military units in order to resist any outside interference in his activities. Müntzer openly challenged and attacked Luther, who was openly opposed to Müntzer’s ministry of the elect, as one of “our mad, debauching pigs, which are horrified by the windstorm, the raging billows and by all the waters of wisdom.”

In his commentary that accompanies the letters, Luther writes, “I write all of this and will have it printed not because I am joyful at the misfortunes of others . . . I only really want to warn all other rebels that they should avoid suffering from the same judgement and anger of God, and should turn away from the harmful false prophets and give themselves up to peace and obedience.” Following Müntzer’s execution on May 27, Luther would write “I killed Müntzer; his death is on my shoulders. But I did it because he wanted to kill my Christ’”. (Brecht Vol II, p. 185)

In these letters Müntzer claims he receives orders from God, threatens to murder aristocrats (calling one a “sack of maggots”), refers to Luther’s theology as “Martin’s peasant gruel”, names the leaders of the Allstedt uprising (see below), and provides updates on peasant revolts in other towns.

The letters were written in April and May 1525, during the Peasants’ War, in the three weeks leading up to the disastrous Battle of Frankenhausen on May 15, in which 5,000 peasants died. Muntzer was captured during the battle and imprisoned, and soon after executed. Luther published this book following Müntzer's execution, a punishment Luther claims was God’s judgement on the rebellion: “You can see how this murderous spirit boasted that God spoke with him and that he fulfilled the will of God and acted as if he would gain everything. And yet, before he could turn around, he lay there with several thousand others in the mud.”

The first letter Luther prints is Müntzer’s letter to the people of Allstedt, written April 26 or 27, in which he tells the people that they must be prepared to suffer for God: “May the pure fear of God be with you, dear brothers. How much longer will you sleep, how much longer will you resist God’s Will . . . if you are not willing to suffer for the sake of God, then you will become martyrs of the Devil.”

Müntzer describes recent successes in the Peasants’ War: “In Fulda in Easter week, four abbeys were laid waste, the peasants of Klettgau and Hegau in the Black Forest have risen, three times one hundred thousand strong, and the army is growing ever greater” and “the people (of Salza) wanted to lay hands on the administrator of Duke Georg because he had secretly wanted to kill three of them.”

Müntzer exhorts the people of Allstedt to take up arms against the nobles: “On, on, onwards, for the fire is hot!”, and he names four men to lead the uprising in Allstedt: “You must set to it, onwards, for it is time. Let Balthasar and Barthel Krump, Valentin and Bischoff lead the dance”.

The second letter is to Müntzer’s “arch-enemy”, Count Ernst of Mansfeld, written on May 12. It was at Ernst’s Heldrungen Castle that Müntzer was tortured following his capture at the Battle of Frankenhausen (May 15.)

Müntzer enumerates the Count’s crimes, including “tyrannical raging”, martyring Christians, and slandering Christianity. He asks the Count, “you miserable, wretched sack of maggots – who made you into a prince over the people whom God redeemed with his own precious blood?”

Count Ernst is promised “safe-conduct” if he repents, but if he refuses “every brother will be prepared to spill their own blood to fight you, as if you were the Turk. Then you will be hunted down and rooted out, for every man will be far keener to gain an indulgence at your expense than any indulgence that the Pope ever offered.”

Müntzer claims to be an instrument of God in destroying the unrepentant Ernst: “we have been given our orders, I say this to you: the eternal living God has commanded that you be cast down from your throne by the power that has been given to us.”

In the third letter, to Albrecht (or Albert) von Mansfeld, Müntzer asks “Have you not been able to spoon up from your Lutheran gruel, your Wittenberg soup, that which Ezekiel prophesied in his 37th chapter? And have you not been able to taste in your Martin’s peasant gruel . . . that God would command all the birds of the air to feast on the flesh of the princes and commanded the unthinking beasts to lap up the blood of the bigwigs, as is described in the secret book of revelations?”

The following day Müntzer again writes to Albrecht in the fourth letter, suggesting a parley between the peasants and the aristocracy: “We invite you and your men to a Christian meeting, with around thirty horsemen, to appear at Mertens Rita just before the bridge, at twelve o’clock tomorrow, Friday.” Instead of a negotiation, the Battle of Frankenhausen took place.

In his commentary on the letters, Luther describes Müntzer’s most fantastical claims: “the peasants could strike five dead with nothing but a felt hat”, “the bullets would turn back in flight and slay the enemy”, and Müntzer’s sleeve would “catch all the bullets which were fired against his people.”

The Peasants’ War was one of the bloodiest chapters in the turbulent early history of the German Reformation. The uprising began in upper Swabia in early 1524 and quickly spread to southern and western Germany, as well as to parts of Switzerland and Austria. The peasants were motivated by a number of factors: crushing taxation, lack of a voice in government, no recourse to the courts, crop failure, and helplessness in the face of their feudal masters’ demands. But whereas these conditions had resulted in smaller uprisings in the past, the massive rebellion of 1524-5 was also a result of the turbulent upheaval caused by the nascent Reformation. By the time the rebellion was crushed in late 1525, some 100,000 combatants and civilians had been killed. Reprisals were carried out for the next two years, and the peasants’ demands, as outlined in their Twelve Articles, came to nothing.

Three of the letters Luther included in this pamphlet are in “The Collected Works of Thomas Müntzer” (Matheson, 1994), they are numbers 75 - “To the People of Allstedt” (composed April 26 or 27), 88 - “To Count Ernst of Mansfeld” and 89 - “To Count Albert von Mansfeld” (both composed on May 12). The fourth letter is also to Count Albert, composed on May 13. All are from 1525. The translation is by Andrew Drummond, author of “The Dreadful History and Judgment of God on Thomas Müntzer” (2024). (Inventory #: 5149)

![Polygraphie et universelle écriture cabalistique. Traduicte par Gabriel de Collange, natif de tours en Auvergne. [with:] Clavicule et interpretation sur le contenu és cinq liures de Polygraphie, & vniuerselle escriture cabalistique, traduicte & augmentée par Gabriel de Collange [and:] Tables et figures planispheriques, extensives & dilatatives des recte & anverse, servants à l'uniuverse intelligence de toutes escritures](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/941/108/1694108941.0.m.jpg)