Carousel content with 1 slides.

A carousel is a rotating set of images, rotation stops on keyboard focus on carousel tab controls or hovering the mouse pointer over images. Use the tabs or the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide.

Hardcover

1635 · Amsterdam

by Brant, Sebastian (1457-1521)

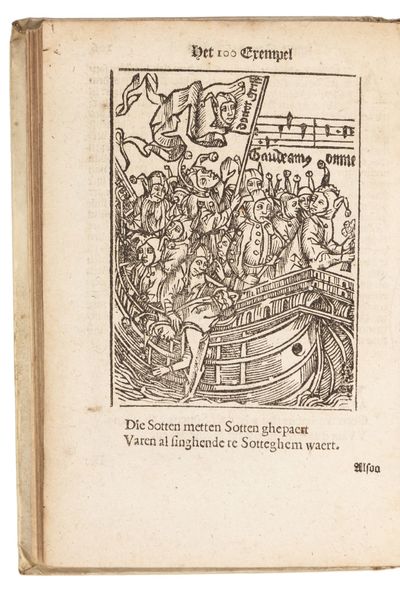

Amsterdam: Jan Evertsz. Cloppenburgh, 1635. SECOND EDITION OF THIS TRANSLATION (1st ed. 1610). Hardcover. Fine. Bound in contemporary Dutch vellum (lightly soiled, corners bumped.) Title lightly soiled, small collector’s mark (Lugt 585), with artist’s tools and monogram “CK”, of the Dutch painter, architect, and art historian Christiaan Kramm (1797-1875). Text with scattered light browning and foxing, some spotting (impurities in the paper), light soiling, insignificant worm-trail in margin of last few leaves. With annotations in Dutch, likely by Kramm, on the fly leaves. Illustrated with a title page engraving showing the Ship of Fools, an engraved (truncated) portrait of the author, and 105 half and three-quarter page woodcuts showing fools in various situations. The woodcuts are drawn from earlier editions, though the exact editions from which they have been taken is unresolved.

A rare, anonymous Dutch translation of Brandt’s famous Narrenschiff. The first edition of this translation appeared in 1610, at Leiden, printed by Henrick Lodewicxsz [Lodewiertz] van Haestens. The first Dutch version to appear in print, not a translation but a drastic reworking by Badius Ascensius, was printed at Paris by Guy Marchant in 1500. Badius soon produced a different translation (Antwerp, 1504). Another translation appeared at Antwerp in 1548 as “Der Sotten schip oft dat narren schip" and yet another in 1584, "Der sotten schip".

Like Badius’ version, this 1610 edition is a free translation, reorganized in keeping with a trend that had been normalized in the 16th c., an early and notable example being Barclay’s English rendering, “The shyp of folys of the worlde”(1509).

For more, see Marynissen and Jansen, “Der zotten ende der narren scip in het kielzog van Dasz Narrenschyff en Stultifera Nauis” in Verslagen en Mededelingen van de Koninklije Academie voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde (September 2016)

The “Ship of Fools” (Dutch “Narren Speel-schuyt”, German “Narrenschiff”, Latin “Stultifera navis”) by the German humanist and poet Sebastian Brant (1458-1521) is an allegorical satire in which a ship laden with and steered by fools sets sail for Narragonia, a “fool's paradise”. The narrative is not confined to the ship itself, but encompasses the whole world of human experience. Brant presents more than 100 fools representing every contemporary shortcoming, both serious and trivial. Criminals, drunkards, ill-behaved priests and lecherous monks, spendthrifts, bribetaking judges, busybodies, and vain and lustful women are included in this unsparing satire. Brant's aims are the improvement of his fellows and the regeneration of church and society.

Brant first published his "Narrenschiff" at Basel in 1494; a second, enlarged German edition appeared the following year (1495), which served as the basis for the Latin translation of the poem (1497) made by Brant’s student and Imperial Poet Laureate Jacob Locher (1471-1528). Locher and Brant produced an expanded Latin edition in 1498, upon which this Dutch translation is based.

“The ‘Ship of Fools’ is the most important of a long line of moralizing works in which the weaknesses and vices of mankind are satirized as follies. The tradition goes back to early medieval times both in England and on the Continent (Lydgate’s ‘Order of Fooles’ and Wireker’s ‘Speculum stultorum’). It was the first original work by a German which passed into world literature... and helped to blaze the trail that leads from medieval allegory to modern satire, drama and the novel of character.

“In a ship laden with one hundred fools, steered by fools to the fools’ paradise of Narragonia, Brant satirizes all the weakness, follies and vices of his time. Composed in popular humorous verse and illustrated by a remarkable series of woodcuts… the book was an immediate success. Incidentally, the book also contains the earliest literary reference to the discovery of America; the Columbus Letter had been published by the same printer the year previously.

“The influence of ‘The Ship of Fools’ was extensive and prolonged: thirty-six editions were published between 1494 and 1513... Its most immediate imitators were Geiler von Kaisersberg, Thomas Murner, Hans Sachs and Johannes Fischart in Germany, where the ‘Narr’ as a type has lived until today. Erasmus’s ‘Moriae Encomium’ was directly inspired by it.”(PMM 37)

The book impressed Brant’s learned contemporaries, including Johannes Trithemius, who compared Brant to Dante and wrote, “Brant should not have called his book a ‘Ship of Fools’ but rather a ‘Divine Satire’”, and the humanist Jacob Wimpheling, who observed, “Brant has interspersed his book so adroitly with stories, fables, and the wisdom of the greatest masters that I do not believe you can find a comparable book in our language.”

Brant’s student and the translator of the “Ship”, the poet Jacob Locher, linked Brant’s work with the Roman satirists, Horace, Persius, and Juvenal. Badius Ascensius, who published Erasmus’ “Praise of Folly” and wrote a work inspired by Brant, “the Ship of Foolish Women”, stressed this same connection when he wrote, “Brant teaches and castigates the infatuated and the foolish who are infinite in number, with his witty and pleasantly readable argumentation, so that they are attracted by his sharp and humorous conversational tone and do not notice that they themselves are the butts of his satire, until he has already crept in on them and is playing with their innermost feelings (as Persius observed about Horace.) Thus he makes them regain their minds and forces them to accept the opinions of the wise, provided that there is any possibility of improvement in them.”(Translation, Gaier, ‘Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff and the Humanists.’ In PMLA, 83: 267). (Inventory #: 5122)

A rare, anonymous Dutch translation of Brandt’s famous Narrenschiff. The first edition of this translation appeared in 1610, at Leiden, printed by Henrick Lodewicxsz [Lodewiertz] van Haestens. The first Dutch version to appear in print, not a translation but a drastic reworking by Badius Ascensius, was printed at Paris by Guy Marchant in 1500. Badius soon produced a different translation (Antwerp, 1504). Another translation appeared at Antwerp in 1548 as “Der Sotten schip oft dat narren schip" and yet another in 1584, "Der sotten schip".

Like Badius’ version, this 1610 edition is a free translation, reorganized in keeping with a trend that had been normalized in the 16th c., an early and notable example being Barclay’s English rendering, “The shyp of folys of the worlde”(1509).

For more, see Marynissen and Jansen, “Der zotten ende der narren scip in het kielzog van Dasz Narrenschyff en Stultifera Nauis” in Verslagen en Mededelingen van de Koninklije Academie voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde (September 2016)

The “Ship of Fools” (Dutch “Narren Speel-schuyt”, German “Narrenschiff”, Latin “Stultifera navis”) by the German humanist and poet Sebastian Brant (1458-1521) is an allegorical satire in which a ship laden with and steered by fools sets sail for Narragonia, a “fool's paradise”. The narrative is not confined to the ship itself, but encompasses the whole world of human experience. Brant presents more than 100 fools representing every contemporary shortcoming, both serious and trivial. Criminals, drunkards, ill-behaved priests and lecherous monks, spendthrifts, bribetaking judges, busybodies, and vain and lustful women are included in this unsparing satire. Brant's aims are the improvement of his fellows and the regeneration of church and society.

Brant first published his "Narrenschiff" at Basel in 1494; a second, enlarged German edition appeared the following year (1495), which served as the basis for the Latin translation of the poem (1497) made by Brant’s student and Imperial Poet Laureate Jacob Locher (1471-1528). Locher and Brant produced an expanded Latin edition in 1498, upon which this Dutch translation is based.

“The ‘Ship of Fools’ is the most important of a long line of moralizing works in which the weaknesses and vices of mankind are satirized as follies. The tradition goes back to early medieval times both in England and on the Continent (Lydgate’s ‘Order of Fooles’ and Wireker’s ‘Speculum stultorum’). It was the first original work by a German which passed into world literature... and helped to blaze the trail that leads from medieval allegory to modern satire, drama and the novel of character.

“In a ship laden with one hundred fools, steered by fools to the fools’ paradise of Narragonia, Brant satirizes all the weakness, follies and vices of his time. Composed in popular humorous verse and illustrated by a remarkable series of woodcuts… the book was an immediate success. Incidentally, the book also contains the earliest literary reference to the discovery of America; the Columbus Letter had been published by the same printer the year previously.

“The influence of ‘The Ship of Fools’ was extensive and prolonged: thirty-six editions were published between 1494 and 1513... Its most immediate imitators were Geiler von Kaisersberg, Thomas Murner, Hans Sachs and Johannes Fischart in Germany, where the ‘Narr’ as a type has lived until today. Erasmus’s ‘Moriae Encomium’ was directly inspired by it.”(PMM 37)

The book impressed Brant’s learned contemporaries, including Johannes Trithemius, who compared Brant to Dante and wrote, “Brant should not have called his book a ‘Ship of Fools’ but rather a ‘Divine Satire’”, and the humanist Jacob Wimpheling, who observed, “Brant has interspersed his book so adroitly with stories, fables, and the wisdom of the greatest masters that I do not believe you can find a comparable book in our language.”

Brant’s student and the translator of the “Ship”, the poet Jacob Locher, linked Brant’s work with the Roman satirists, Horace, Persius, and Juvenal. Badius Ascensius, who published Erasmus’ “Praise of Folly” and wrote a work inspired by Brant, “the Ship of Foolish Women”, stressed this same connection when he wrote, “Brant teaches and castigates the infatuated and the foolish who are infinite in number, with his witty and pleasantly readable argumentation, so that they are attracted by his sharp and humorous conversational tone and do not notice that they themselves are the butts of his satire, until he has already crept in on them and is playing with their innermost feelings (as Persius observed about Horace.) Thus he makes them regain their minds and forces them to accept the opinions of the wise, provided that there is any possibility of improvement in them.”(Translation, Gaier, ‘Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff and the Humanists.’ In PMLA, 83: 267). (Inventory #: 5122)

![Polygraphie et universelle écriture cabalistique. Traduicte par Gabriel de Collange, natif de tours en Auvergne. [with:] Clavicule et interpretation sur le contenu és cinq liures de Polygraphie, & vniuerselle escriture cabalistique, traduicte & augmentée par Gabriel de Collange [and:] Tables et figures planispheriques, extensives & dilatatives des recte & anverse, servants à l'uniuverse intelligence de toutes escritures](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/941/108/1694108941.0.m.jpg)