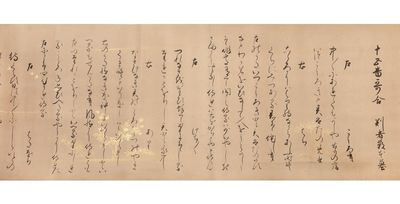

by NAKAMURA, Kyūetsu 中村久越, calligrapher

Scroll (277 x 7640 mm.), background decorations of flowers, butterflies, & birds in gold throughout, gold-speckled front endpaper, outside of endpaper covered with blue & gold silk brocade, wooden core roller. [Japan]: early Edo.

THE SCROLL & ITS CALLIGRAPHY: A beautifully written calligraphic scroll, attributed to Nakamura Kyūetsu, the noted calligrapher. He was a priest at Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine in Yamashiro Province (in today’s Kyoto prefecture), where he studied calligraphy under the Shingon monk Shōkadō Shōjō (1584-1639), one of the three leading Kyoto calligraphers of the early 17th century. Later, Kyūetsu enjoyed (truncated)

THE SCROLL & ITS CALLIGRAPHY: A beautifully written calligraphic scroll, attributed to Nakamura Kyūetsu, the noted calligrapher. He was a priest at Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine in Yamashiro Province (in today’s Kyoto prefecture), where he studied calligraphy under the Shingon monk Shōkadō Shōjō (1584-1639), one of the three leading Kyoto calligraphers of the early 17th century. Later, Kyūetsu enjoyed (truncated)