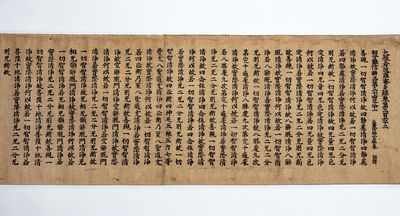

by SUTRA OF PERFECTION OF WISDOM (KASUGA-BAN 春日版)

22-23 columns per sheet, 17 characters per column (column height 205 mm.), printed on 19 joined sheets (263 mm. high; sheet lengths ranging from 428-443 mm.; total length, including front endpaper: 8480 mm.), attached at end to a wooden roller. [Nara: Kamakura era].

A rare early woodblock-printed sutra, issued on high-quality thick paper (gampi, or mulberry fibers), and printed in bold, thick strokes, using black sumi ink, typical of Kamakura and Muromachi kasuga-ban printings (kasuga-ban is a general term for publications of the Nara monasteries).

The Mahaprajnaparamitasutra is a massive compilation of scriptural literature (truncated)

A rare early woodblock-printed sutra, issued on high-quality thick paper (gampi, or mulberry fibers), and printed in bold, thick strokes, using black sumi ink, typical of Kamakura and Muromachi kasuga-ban printings (kasuga-ban is a general term for publications of the Nara monasteries).

The Mahaprajnaparamitasutra is a massive compilation of scriptural literature (truncated)