Hardcover

1494 · Venice

by Catherine of Siena, Saint [Caterina Benincasa] (Siena 1347- Rome 1380)

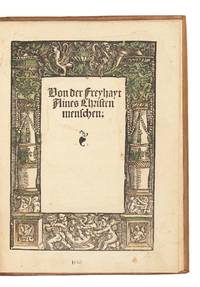

Venice: Matteo Capcasa di Codeca for Lucantonio Giunta, 17 May, 1494. FIRST ILLUSTRATED EDITION, THE FIRST WITH THE LIFE OF THE SAINT, and the third edition overall (1st printed at Bologna ca. 1475; 2nd ed. Naples 1478). Hardcover. Fine. Bound in 20th c. brown morocco, with gilt turn-ins. With two full-page and one smaller woodcut. Text lightly washed, blank corners of the opening leaves carefully restored, very slightly affecting the border of the first woodcut. With a near-contemporary inscription of the Church of San Prospero in Reggio Emilia. A few minor stains, small piece clipped from blank margin of leaf D8. This is the variant with the wrong printing date and the spelling "mestro lucantonio de zonta" in the colophon as well as with the textual difference on page AA2 noted by GW in note 1. Very rare. Five copies in North America: Harvard, Huntington, LC, NYPL, Toronto. An early, rare, and beautiful edition of “Il libro della divina dottrina”, “The Book of Divine Doctrine” (also called the “Dialogue”), the culminating theological work of the Dominican tertiary mystic Saint Catherine of Siena (canonized 1461, feast day 29 April). The first woodcut shows Catherine seated on a throne, with Siena in the background, and handing copies of her book to the wives of Lodovico and Galeazo Sforza; the second (leaf a1) shows her dictating to three secretaries while in ecstasy; the third (leaf x7 verso) shows her in prayer before an altar.

Catherine composed the book, which takes the form of an inner conversation between the soul and God, two years before her death. Tradition held that Catherine dictated the work to her secretaries over the course of five days while she was in the throes of ecstasy. Historical evidence indicates that it was probably dictated over a period of months between December 1377 and October 1378.

This edition is dedicated to Isabella d’Este, wife of Giovanni Galeazo Sforza, duke of Milan, and Beatrice d’Aragona, wife of Lodovico Sforza, duke of Barri. It includes additional texts, most notably, a life of the saint composed by an unnamed Dominican, drawn from the documents presented during the canonization process; Barduccio Canigiani’s eyewitness account of Catherine’s death; and two texts by Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini), who canonized Catherine.

“The ‘Dialogue’ deals with the whole plan of salvation, with particular emphasis on Jesus Christ as the Bridge which unites man to God. Although it contains a rich theological doctrine, it does not present a systematic development of ideas. Catherine is not interested in speculative scholasticism; rather, she is moved by practical considerations. This is obvious from the first chapter of the Dialogue , where she addresses four petitions to the Eternal Father: (1) for herself; (2) for the reformation of the Church; (3) for the needs of the whole world; and (4) a petition to divine providence to provide for things in general and in particular. The rest of the Dialogue is taken up with the Father's response to these four petitions with interjections now and again from Catherine…

“God's love for us in creation is so great that, according to Catherine, it reaches a point of ‘madness’. In the last chapter, overcome by the realization of this ‘madness’ of love, she writes: ‘I confess and do not deny that you loved me before I existed and that you loved me unspeakably, as if you were mad with love for your creature.’

“Contemplating the Incarnation, Catherine cannot understand how God can love us so much that he would take on the lowliness of human nature: ‘O abyss of love, what heart can help breaking when it sees such dignity as yours descend to such lowliness as our humanity? ... For what reason? Love. By this love, O God, you have become man, and man has become God.’ As in the case of Creation, so again, in the context of the Incarnation, Catherine exclaims that God must be ‘mad’ with love for us: ‘It seems, O abyss of love, as if you were mad with love for your creature, as if you could not live without him; and, yet, you are God who has no need of us.’

“The death of Jesus Christ is the supreme expression of God's mad love for man. Addressing Jesus Christ directly -something which she does rarely- Catherine asks: ‘O loving madman, was it not enough for you to become incarnate, without also wishing to die?’ She is convinced that nails would never have held Jesus Christ to the cross, if love had not held him there.”(O’Driscoll)

“Catherine was the youngest of 25 children born to a lower middle-class family; most of her siblings did not survive childhood. At a young age she is said to have consecrated her virginity to Christ and experienced mystical visions. Convinced of her devotion, Catherine’s parents gave her a small room in the basement of their home that acted as a hermitage. She slept on a board, used a wooden log for a pillow, and meditated on her only spiritual token, a crucifix. She claimed to have received an invisible (for humility) stigmata by which she felt the wounds of Christ.

“At the age of 19, after a three-year seclusion, Catherine experienced what she later described as ‘spiritual marriage’ to Christ. In this vision, Jesus placed a ring on her finger, and her soul attained mystical union with God. She called this state an ‘inner cell in her soul’ that sustained her all her life as she traveled and ministered.

“Catherine became a tertiary (member of a monastic third order who takes simple vows and may remain outside a convent or monastery) of the Dominican order (1363), joining the Sisters of Penitence of St. Dominic in Siena. She rapidly gained a wide reputation for her holiness and her severe asceticism. In her early twenties she experienced a ‘spiritual espousal’ to Christ and was moved to immediately begin serving the poor and sick, gaining disciples in the process.

“Her ministry eventually moved beyond her local community, and Catherine began to travel and promote church reform. When the rebellious city of Florence was placed under an interdict by Pope Gregory XI (1376), Catherine determined to take public action for peace within the church and Italy and to encourage a Crusade against the Muslims. She went as an unofficial mediator to Avignon with her confessor and biographer Raymond of Capua. Her mission failed, and she was virtually ignored by the pope, but while at Avignon she promoted her plans for a Crusade.

“It became clear to her that the return of Pope Gregory XI to Rome from Avignon—an idea that she did not initiate and had not strongly encouraged—was the only way to bring peace to Italy. Catherine left for Tuscany the day after Gregory set out for Rome (1376). At his request she went to Florence (1378) and was there during the Ciompi Revolt in June. After a short final stay in Siena, during which she completed ‘The Dialogue’ (begun the previous year), she went to Rome in November, probably at the invitation of Pope Urban VI, whom she helped in reorganizing the church. From Rome she sent out letters and exhortations to gain support for Urban; as one of her last efforts, she tried to win back Queen Joan I of Naples to obedience to Urban, who had excommunicated the queen for supporting the antipope Clement VII.

“The record of her ecstatic experiences in ‘The Dialogue’ illustrates her doctrine of the ‘inner cell’ of the knowledge of God and of self into which she withdrew. Catherine also composed about 380 letters and 26 prayers.”(Britannica). (Inventory #: 5177)

Catherine composed the book, which takes the form of an inner conversation between the soul and God, two years before her death. Tradition held that Catherine dictated the work to her secretaries over the course of five days while she was in the throes of ecstasy. Historical evidence indicates that it was probably dictated over a period of months between December 1377 and October 1378.

This edition is dedicated to Isabella d’Este, wife of Giovanni Galeazo Sforza, duke of Milan, and Beatrice d’Aragona, wife of Lodovico Sforza, duke of Barri. It includes additional texts, most notably, a life of the saint composed by an unnamed Dominican, drawn from the documents presented during the canonization process; Barduccio Canigiani’s eyewitness account of Catherine’s death; and two texts by Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini), who canonized Catherine.

“The ‘Dialogue’ deals with the whole plan of salvation, with particular emphasis on Jesus Christ as the Bridge which unites man to God. Although it contains a rich theological doctrine, it does not present a systematic development of ideas. Catherine is not interested in speculative scholasticism; rather, she is moved by practical considerations. This is obvious from the first chapter of the Dialogue , where she addresses four petitions to the Eternal Father: (1) for herself; (2) for the reformation of the Church; (3) for the needs of the whole world; and (4) a petition to divine providence to provide for things in general and in particular. The rest of the Dialogue is taken up with the Father's response to these four petitions with interjections now and again from Catherine…

“God's love for us in creation is so great that, according to Catherine, it reaches a point of ‘madness’. In the last chapter, overcome by the realization of this ‘madness’ of love, she writes: ‘I confess and do not deny that you loved me before I existed and that you loved me unspeakably, as if you were mad with love for your creature.’

“Contemplating the Incarnation, Catherine cannot understand how God can love us so much that he would take on the lowliness of human nature: ‘O abyss of love, what heart can help breaking when it sees such dignity as yours descend to such lowliness as our humanity? ... For what reason? Love. By this love, O God, you have become man, and man has become God.’ As in the case of Creation, so again, in the context of the Incarnation, Catherine exclaims that God must be ‘mad’ with love for us: ‘It seems, O abyss of love, as if you were mad with love for your creature, as if you could not live without him; and, yet, you are God who has no need of us.’

“The death of Jesus Christ is the supreme expression of God's mad love for man. Addressing Jesus Christ directly -something which she does rarely- Catherine asks: ‘O loving madman, was it not enough for you to become incarnate, without also wishing to die?’ She is convinced that nails would never have held Jesus Christ to the cross, if love had not held him there.”(O’Driscoll)

“Catherine was the youngest of 25 children born to a lower middle-class family; most of her siblings did not survive childhood. At a young age she is said to have consecrated her virginity to Christ and experienced mystical visions. Convinced of her devotion, Catherine’s parents gave her a small room in the basement of their home that acted as a hermitage. She slept on a board, used a wooden log for a pillow, and meditated on her only spiritual token, a crucifix. She claimed to have received an invisible (for humility) stigmata by which she felt the wounds of Christ.

“At the age of 19, after a three-year seclusion, Catherine experienced what she later described as ‘spiritual marriage’ to Christ. In this vision, Jesus placed a ring on her finger, and her soul attained mystical union with God. She called this state an ‘inner cell in her soul’ that sustained her all her life as she traveled and ministered.

“Catherine became a tertiary (member of a monastic third order who takes simple vows and may remain outside a convent or monastery) of the Dominican order (1363), joining the Sisters of Penitence of St. Dominic in Siena. She rapidly gained a wide reputation for her holiness and her severe asceticism. In her early twenties she experienced a ‘spiritual espousal’ to Christ and was moved to immediately begin serving the poor and sick, gaining disciples in the process.

“Her ministry eventually moved beyond her local community, and Catherine began to travel and promote church reform. When the rebellious city of Florence was placed under an interdict by Pope Gregory XI (1376), Catherine determined to take public action for peace within the church and Italy and to encourage a Crusade against the Muslims. She went as an unofficial mediator to Avignon with her confessor and biographer Raymond of Capua. Her mission failed, and she was virtually ignored by the pope, but while at Avignon she promoted her plans for a Crusade.

“It became clear to her that the return of Pope Gregory XI to Rome from Avignon—an idea that she did not initiate and had not strongly encouraged—was the only way to bring peace to Italy. Catherine left for Tuscany the day after Gregory set out for Rome (1376). At his request she went to Florence (1378) and was there during the Ciompi Revolt in June. After a short final stay in Siena, during which she completed ‘The Dialogue’ (begun the previous year), she went to Rome in November, probably at the invitation of Pope Urban VI, whom she helped in reorganizing the church. From Rome she sent out letters and exhortations to gain support for Urban; as one of her last efforts, she tried to win back Queen Joan I of Naples to obedience to Urban, who had excommunicated the queen for supporting the antipope Clement VII.

“The record of her ecstatic experiences in ‘The Dialogue’ illustrates her doctrine of the ‘inner cell’ of the knowledge of God and of self into which she withdrew. Catherine also composed about 380 letters and 26 prayers.”(Britannica). (Inventory #: 5177)