signed Hardcover

1525 · [Erfurt]

by Müntzer, Thomas (1489-1525)

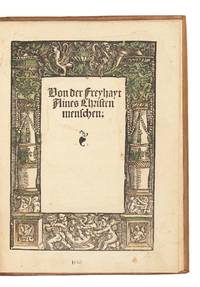

[Erfurt]: [Johann Loersfeld], 1525. ONE OF SIX PRINTINGS, all printed in 1525, priority not established. Hardcover. Fine. Modern wrappers. With a woodcut title border (Luther 69), showing a grape arbor populated by a monkey, a stork, and armed putti, first used in 1523 by the printer Michael Buchführer (with his initials.) A very good copy of this rarity, with early marginalia throughout. Lower blank corner of the title page snipped away and restored (without affecting the text.) This edition is the first (B 1550) listed in VD16. However, Claus (“Der deutsche Bauernkrieg im Druckschaffen der Jahre 1524-1526”) lists this third, after the Leipzig editions printed by Wolfgang Stöckel (VD16 B 1553) and Michael Blum (VD16 B 1552). An extremely rare printing of Thomas Müntzer’s confession that was obtained under torture following his capture at the Battle of Frankenhausen in May 1525. Müntzer, the “murderous and bloodthirsty prophet” and the most significant figure in the second, crucial phase of the Peasants’ War (Bauernkrieg), one of the bloodiest chapters in the turbulent early history of the German Reformation, which left over 100,000 dead.

In this confession Müntzer names many of his co-conspirators, and admits that his plans included beheading Count Ernest von Mansfeld, and seizing the wealth and lands of the aristocracy. This book also includes Müntzer's final letter begging that his wife avoid punishment and inherit his property, and that his followers “flee the shedding of blood”.

In 1523, Müntzer, formerly the leader of the radical “Zwickau Prophets” began to radicalize the area of Allstedt, where he was then pastor, preaching that the ungodly were to be eliminated and the elect would establish a kingdom of Christ on earth and threatening the political rulers of the area with rebellion. In early 1524, as Müntzer grew bolder in his denunciation of the authorities and called for an elimination of the enemies of God, he divided the citizenry into military units in order to resist any outside interference in his activities. Müntzer openly challenged and attacked Luther, who was openly opposed to Müntzer’s ministry of the elect, as one of “our mad, debauching pigs, which are horrified by the windstorm, the raging billows and by all the waters of wisdom.”

On May 27, Müntzer was beheaded outside the gates of Mühlhausen, his body impaled, and his head stuck on a stake, where it remained for years. Martin Luther wrote “I killed Müntzer; his death is on my shoulders. But I did it because he wanted to kill my Christ”. (Brecht 185)

Müntzer’s interrogation and torture were conducted at Heldrungen, the castle of his arch-enemy Count Ernest von Mansfeld, beginning May 16, 1525. During the interrogation Müntzer names the original members of the alliance (Balthasar Krump, a tanner, and Baltzer Stübner, a glazier, both of Allstedt), and said that when he arrived in Mühlhausen he was welcomed by two men (Hans Rotte, a furrier, and the distiller near St. Blasius).

While being tortured, Müntzer provided the names of numerous participants in the alliance, and admitted “that if he had taken the castle at Heldrungen, he and all his followers had intended to cut off the head of Count Ernest, and that he had often talked of doing this.”

Müntzer also described the alliance's plan to seize the lands and wealth of the aristocracy, abolish private property, and execute those who did not comply: “all things are to be held in common and distribution should be to each according to his need, as occasion arises. Any prince, count, or gentleman who refused to do this should first be given a warning, but then one should cut off his head or hang him.

According to Müntzer, the ultimate goal of the alliance was “to appropriate all the land within a forty-six mile radius of Mühlhausen and the land in Hesse, and to deal with the princes and gentry as described above.”

This text was printed by Luther’s ally Johann Loersfeld about two weeks after Müntzer’s capture, and “in view of this propaganda use, caution is in place about its complete accuracy as a record of Müntzer’s replies”. (Matheson 433)

Müntzer’s final letter, composed on May 17, 1525 is also printed here. In it, he appeals to the Christian community and the Council of Mühlhausen to look after his wife: “I would ask you in a friendly way to see that my wife inherits my property, for example, such books and clothes as there are; for God’s sake do not let it be taken out on her. Dear brothers, it is quite crucial that this be so.”

In conclusion he calls for peace and an end to the rebellion - exhorting his allies to “flee the shedding of blood”, and “shun all gatherings and disturbances and seek the mercy of the princes” in order to “to avoid innocent people like yourselves being drawn into grave trouble, as happened to some people at Frankenhausen.”

“Many of his later letters . . . are signed not as an individual, but as the servant of God, the disturber of the godless, the wielder of the sword of Gideon. The reversion, in his very last letter, to the simple signature ‘Thomas Müntzer’, indicates the collapse of his mission.” (Matheson 5)

The Peasants’ War was one of the bloodiest chapters in the turbulent early history of the German Reformation. The uprising began in upper Swabia in early 1524 and quickly spread to southern and western Germany, as well as to parts of Switzerland and Austria. The peasants were motivated by a number of factors: crushing taxation, lack of a voice in government, no recourse to the courts, crop failure, and helplessness in the face of their feudal masters’ demands. But whereas these conditions had resulted in smaller uprisings in the past, the massive rebellion of 1524-5 was also a result of the turbulent upheaval caused by the nascent Reformation. By the time the rebellion was crushed in late 1525, some 100,000 combatants and civilians had been killed. Reprisals were carried out for the next two years, and the peasants’ demands, as outlined in their Twelve Articles, came to nothing. (Inventory #: 5148)

In this confession Müntzer names many of his co-conspirators, and admits that his plans included beheading Count Ernest von Mansfeld, and seizing the wealth and lands of the aristocracy. This book also includes Müntzer's final letter begging that his wife avoid punishment and inherit his property, and that his followers “flee the shedding of blood”.

In 1523, Müntzer, formerly the leader of the radical “Zwickau Prophets” began to radicalize the area of Allstedt, where he was then pastor, preaching that the ungodly were to be eliminated and the elect would establish a kingdom of Christ on earth and threatening the political rulers of the area with rebellion. In early 1524, as Müntzer grew bolder in his denunciation of the authorities and called for an elimination of the enemies of God, he divided the citizenry into military units in order to resist any outside interference in his activities. Müntzer openly challenged and attacked Luther, who was openly opposed to Müntzer’s ministry of the elect, as one of “our mad, debauching pigs, which are horrified by the windstorm, the raging billows and by all the waters of wisdom.”

On May 27, Müntzer was beheaded outside the gates of Mühlhausen, his body impaled, and his head stuck on a stake, where it remained for years. Martin Luther wrote “I killed Müntzer; his death is on my shoulders. But I did it because he wanted to kill my Christ”. (Brecht 185)

Müntzer’s interrogation and torture were conducted at Heldrungen, the castle of his arch-enemy Count Ernest von Mansfeld, beginning May 16, 1525. During the interrogation Müntzer names the original members of the alliance (Balthasar Krump, a tanner, and Baltzer Stübner, a glazier, both of Allstedt), and said that when he arrived in Mühlhausen he was welcomed by two men (Hans Rotte, a furrier, and the distiller near St. Blasius).

While being tortured, Müntzer provided the names of numerous participants in the alliance, and admitted “that if he had taken the castle at Heldrungen, he and all his followers had intended to cut off the head of Count Ernest, and that he had often talked of doing this.”

Müntzer also described the alliance's plan to seize the lands and wealth of the aristocracy, abolish private property, and execute those who did not comply: “all things are to be held in common and distribution should be to each according to his need, as occasion arises. Any prince, count, or gentleman who refused to do this should first be given a warning, but then one should cut off his head or hang him.

According to Müntzer, the ultimate goal of the alliance was “to appropriate all the land within a forty-six mile radius of Mühlhausen and the land in Hesse, and to deal with the princes and gentry as described above.”

This text was printed by Luther’s ally Johann Loersfeld about two weeks after Müntzer’s capture, and “in view of this propaganda use, caution is in place about its complete accuracy as a record of Müntzer’s replies”. (Matheson 433)

Müntzer’s final letter, composed on May 17, 1525 is also printed here. In it, he appeals to the Christian community and the Council of Mühlhausen to look after his wife: “I would ask you in a friendly way to see that my wife inherits my property, for example, such books and clothes as there are; for God’s sake do not let it be taken out on her. Dear brothers, it is quite crucial that this be so.”

In conclusion he calls for peace and an end to the rebellion - exhorting his allies to “flee the shedding of blood”, and “shun all gatherings and disturbances and seek the mercy of the princes” in order to “to avoid innocent people like yourselves being drawn into grave trouble, as happened to some people at Frankenhausen.”

“Many of his later letters . . . are signed not as an individual, but as the servant of God, the disturber of the godless, the wielder of the sword of Gideon. The reversion, in his very last letter, to the simple signature ‘Thomas Müntzer’, indicates the collapse of his mission.” (Matheson 5)

The Peasants’ War was one of the bloodiest chapters in the turbulent early history of the German Reformation. The uprising began in upper Swabia in early 1524 and quickly spread to southern and western Germany, as well as to parts of Switzerland and Austria. The peasants were motivated by a number of factors: crushing taxation, lack of a voice in government, no recourse to the courts, crop failure, and helplessness in the face of their feudal masters’ demands. But whereas these conditions had resulted in smaller uprisings in the past, the massive rebellion of 1524-5 was also a result of the turbulent upheaval caused by the nascent Reformation. By the time the rebellion was crushed in late 1525, some 100,000 combatants and civilians had been killed. Reprisals were carried out for the next two years, and the peasants’ demands, as outlined in their Twelve Articles, came to nothing. (Inventory #: 5148)