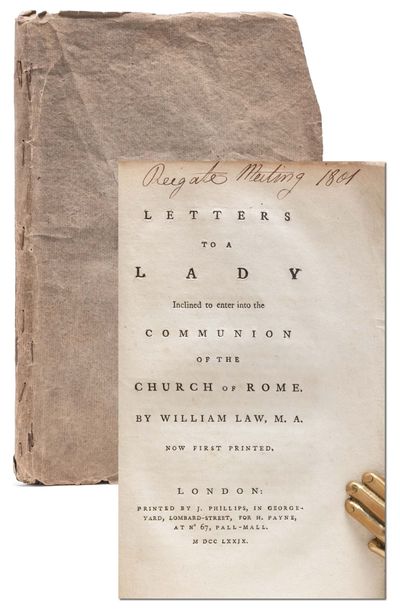

first edition

1779 · London

by Law, William [Dodwell, Elizabeth]

London: Printed by J. Phillips...for H. Payne, 1779. First edition. Very Good +. Octavo. [iv], 98, [2] pp. Complete with the half-title and final leaf of advertisements. Contemporary brown paper wrappers, somewhat crinkled and chipped at edges. Clean and fresh throughout aside from some dustsoiling to first leaf and last couple leaves. Ink ownership signature ("Reigate Meeting 1801") to margin of title-page. Edges untrimmed. A remarkably clean, large copy, Very Good+

First edition, published eighteen year's after William Law's death, of these three letters likely written to Elizabeth Dodwell, the daughter of nonjuror and theologian Henry Dodwell (truncated)

First edition, published eighteen year's after William Law's death, of these three letters likely written to Elizabeth Dodwell, the daughter of nonjuror and theologian Henry Dodwell (truncated)