Carousel content with 1 slides.

A carousel is a rotating set of images, rotation stops on keyboard focus on carousel tab controls or hovering the mouse pointer over images. Use the tabs or the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide.

Hardcover

1537 · Venice

by Mandeville, John (fl. 14th c.)

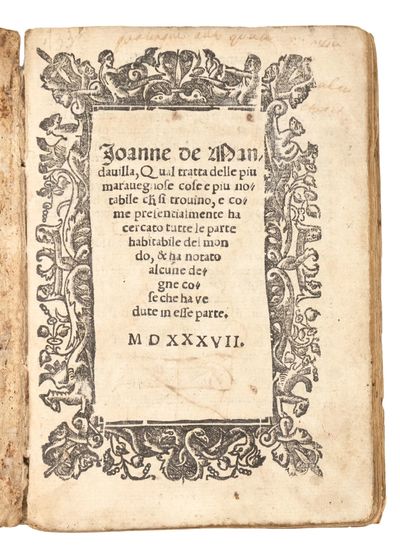

Venice: per Aluise Torti, 1537. A rare Italian edition of John Mandeville’s “Travels”. The first Italian edition appeared in 1480 at Milan. Hardcover. Fine. An unsophisticated copy bound in its original carta rustica binding (soiled, surface wear, small losses at head of spine and small defect at foot.) Contents shaken, title soiled, mild damp-staining and soiling to the text, very slim worm-trail in lower margin of some gatherings, just entering the text in a few places. Title page with woodcut border. Small stains on lsv. +2-4 and B8. A wildly successful collection of medieval travelers’ tales to the Holy Land, China, India, and other exotic lands (truncated) both real (Ethiopia) and imagined (the land of the Amazons), embellished with accounts of strange peoples and fantastic animals, all narrated by a certain John Mandeville, based (so he claims) on his own experiences, and offered as a guide for would-be travelers. “The actual author of the tales remains as uncertain as the existence of the English knight Sir John Mandeville himself. The book originated in French about 1356–57 and was soon translated into many languages, an English version appearing about 1375. The narrator Mandeville identifies himself as a knight of St. Albans. Incapacitated by arthritic gout, he has undertaken to stave off boredom by writing of his travels, which began on Michaelmas Day (September 29) 1322, and from which he returned in 1356.”(EB)

“The book was a contemporary bestseller, providing readers with exotic information about locales from Constantinople to China and about the social and religious practices of peoples such as the Greeks, Muslims, and Brahmins. The book first appeared in the middle of the fourteenth century and by the next century could be found in an extraordinary range of European languages. Its wide readership is also attested by the two hundred and fifty to three hundred medieval manuscripts that still survive today. One scholar even insists that “few literate men in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries could have avoided coming across the Travels at some time.” Among others, Chaucer borrowed from it; Christopher Columbus apparently consulted the work, as did Sir Walter Ralegh.

“The sources that lie behind the work are so many and varied that a better alternative title for the work than ‘Mandeville’s Travels’ might have been ‘Mandeville’s Library’. The two most important works behind the book were written in the 1330s by authentic clerical travelers. The primary source for the first part of the Book (travel to and around Jerusalem) is the Liber de Quibusdam Ultramarinis Partibus (a.k.a. the Itinerarius) by the German Dominican William of Boldensele, whereas that for the second part (travel farther east) is Friar Odoric of Pordenone’s Itinerarius, which tells of the Franciscan’s missionary experiences in China and India. Portions of many other works, also apparently known to the Mandeville-author primarily in French translation, were also used to make up the Book: these include some of the most learned and influential reference works of the Middle Ages, such as Vincent de Beauvais’ Speculum Historiale and Speculum Naturale and Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Tresors, as well as older authorities such as Macrobius and Isidore of Seville. Scholars have also identified material taken from other travel books and from writings as varied as saints’ lives (Jacobus of Voragine’s Legenda Aurea), historical romances (those about Alexander), and at least one scientific work (John of Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera). The author’s skill as a compiler is revealed in the deftness with which he melds these various sources into a convincing whole, principally by means of the voice and personality of his narrator: the alert, energetic, and always eager to instruct Sir John Mandeville…

“The Book begins with a preface that seems to present the work as a guide for pilgrims to Jerusalem, a well-known medieval genre. Sir John announces that in addition to the Holy Land, he has journeyed to stranger, non-biblical lands, including Ethiopia and India [and] promises to tell of “many diverse folk of manners and diverse laws and shapes”. The Book proper opens with a description of Constantinople and the routes by which to go there. Dramatic contrasts in subject matter, such as the description of St. John the Evangelist’s tomb at Ephesus followed by a story of a woman changed into a dragon who can return to human shape only with a knight’s kiss, enliven the Book.

“Sir John then gives various routes to Jerusalem and outlines the sights along their ways. After a large section about Egypt, the works tells about the Holy Land itself. Important surrounding sites are recorded, such as Bethlehem, but it is Jerusalem that is described in most detail, especially those places associated with major Jewish figures such as David and with the life and death of Christ. At times, the account reads very much like a guide for travelers: we are told of the spatial relationship of one building to another and specific points of their individual architecture. Sir John emphasizes that Jerusalem is now controlled by Muslims, and he records a long conversation that he had with their Sultan, who details the many moral failings of contemporary Christians that have caused God to deprive them of the Holy Land.

“Although Jerusalem may be at the center of the world and the ultimate aim of religious pilgrims, it cannot hold such an insatiable traveler as Sir John. He is soon away to more remote and exotic climes and cultures. After passing through Armenia, he continues further east through the land of Job, the country of the Amazons, and Ethiopia, some of whose people have only one foot, which, in addition to propelling them quickly, serves to shade their bodies from the sun. Sir John eventually reaches the lands around India with their various and exotic religions — some worship snakes (lines 1586–87) and others allow themselves to be crushed under the wheels of a chariot bearing their idol (lines 1655–59). After a discussion of the roundness of the world (lines 1687–1778) and mention of additional marvels, such as men and women with heads like dogs (lines 1854–68) or others with both male and female genitals (lines 1892–95), Sir John arrives in China and describes the almost unimaginable wealth, luxury, and pomp at the court of the Great Khan with a full account of the realm’s particular laws and customs (lines 1968–2017, 2100 ff.). As he continues on, Sir John encounters additional strange beings and practices, and, after a warning about the dangers that Jews will pose at the time of the Antichrist (lines 2366–82), he describes Prester John (an emperor and a priest), who though allied with the Khan is a Christian, but not a Catholic (lines 2392 ff.). Near the end of his Book, Sir John describes a kind of ideal society: that of the Brahmins and Synoplians, who even though they lack Christian revelation follow its essential precepts by natural law and whose faith, simple life, and love and charity toward one another make them beloved of God (lines 2573–2637). After observing gold-digging ants in Ceylon, passing by but not being able to visit the Earthly Paradise (lines 2681–2706), and describing the Tibetan practice by which a son honors his dead father by offering his body to birds and the flesh of his head to special friends (lines 2763–83), Sir John, having circumnavigated the earth, returns home to England to rest in his old age.

“Debate about the identity of the author also continues. Some popular English opinion still holds out for Sir John Mandeville — there is a plaque in his honor in St. Albans Cathedral and a Fleet Street veteran has recently taken up his cause — but scholars have also suggested other candidates, including Jean d’Outremeuse, a notary of Liège, and Brother Jean de Long of the Benedictine Abbey Church of St. Bertin. It seems unlikely that we shall ever be certain about the authorship of the Book. Indeed, applying the term author to this work is imprecise and somewhat misleading. Obviously someone first assembled the materials we know as The Book of John Mandeville, but, as has been noted, he borrowed rather than created most of those contents. Rather than a wholly original author, Mandeville is best considered a compiler, one who collects and rearranges the writings of others into a new form.

Just as whoever first put together the Book combined and rewrote previous texts, the work he produced proved equally malleable, for it was itself, in turn, adapted, abridged, and supplemented by later redactors in a variety of ways including but not limited to the kinds of alterations to the narrative voice we have already discussed. What we call the Book resists precise definition because it differs from version to version as well as from text to text within a particular version. The Book of John Mandeville refers less to a single stable entity than to what Iain Higgins, in the most illuminating current study of the work, has called a “multi-text.” The original composition of the Book did not fix the work because it was so quickly and variously transformed by those who received it.” (Kohanski and Benson, The Book of John Mandeville: Introduction (2007)). (Inventory #: 5104)

“The book was a contemporary bestseller, providing readers with exotic information about locales from Constantinople to China and about the social and religious practices of peoples such as the Greeks, Muslims, and Brahmins. The book first appeared in the middle of the fourteenth century and by the next century could be found in an extraordinary range of European languages. Its wide readership is also attested by the two hundred and fifty to three hundred medieval manuscripts that still survive today. One scholar even insists that “few literate men in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries could have avoided coming across the Travels at some time.” Among others, Chaucer borrowed from it; Christopher Columbus apparently consulted the work, as did Sir Walter Ralegh.

“The sources that lie behind the work are so many and varied that a better alternative title for the work than ‘Mandeville’s Travels’ might have been ‘Mandeville’s Library’. The two most important works behind the book were written in the 1330s by authentic clerical travelers. The primary source for the first part of the Book (travel to and around Jerusalem) is the Liber de Quibusdam Ultramarinis Partibus (a.k.a. the Itinerarius) by the German Dominican William of Boldensele, whereas that for the second part (travel farther east) is Friar Odoric of Pordenone’s Itinerarius, which tells of the Franciscan’s missionary experiences in China and India. Portions of many other works, also apparently known to the Mandeville-author primarily in French translation, were also used to make up the Book: these include some of the most learned and influential reference works of the Middle Ages, such as Vincent de Beauvais’ Speculum Historiale and Speculum Naturale and Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Tresors, as well as older authorities such as Macrobius and Isidore of Seville. Scholars have also identified material taken from other travel books and from writings as varied as saints’ lives (Jacobus of Voragine’s Legenda Aurea), historical romances (those about Alexander), and at least one scientific work (John of Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera). The author’s skill as a compiler is revealed in the deftness with which he melds these various sources into a convincing whole, principally by means of the voice and personality of his narrator: the alert, energetic, and always eager to instruct Sir John Mandeville…

“The Book begins with a preface that seems to present the work as a guide for pilgrims to Jerusalem, a well-known medieval genre. Sir John announces that in addition to the Holy Land, he has journeyed to stranger, non-biblical lands, including Ethiopia and India [and] promises to tell of “many diverse folk of manners and diverse laws and shapes”. The Book proper opens with a description of Constantinople and the routes by which to go there. Dramatic contrasts in subject matter, such as the description of St. John the Evangelist’s tomb at Ephesus followed by a story of a woman changed into a dragon who can return to human shape only with a knight’s kiss, enliven the Book.

“Sir John then gives various routes to Jerusalem and outlines the sights along their ways. After a large section about Egypt, the works tells about the Holy Land itself. Important surrounding sites are recorded, such as Bethlehem, but it is Jerusalem that is described in most detail, especially those places associated with major Jewish figures such as David and with the life and death of Christ. At times, the account reads very much like a guide for travelers: we are told of the spatial relationship of one building to another and specific points of their individual architecture. Sir John emphasizes that Jerusalem is now controlled by Muslims, and he records a long conversation that he had with their Sultan, who details the many moral failings of contemporary Christians that have caused God to deprive them of the Holy Land.

“Although Jerusalem may be at the center of the world and the ultimate aim of religious pilgrims, it cannot hold such an insatiable traveler as Sir John. He is soon away to more remote and exotic climes and cultures. After passing through Armenia, he continues further east through the land of Job, the country of the Amazons, and Ethiopia, some of whose people have only one foot, which, in addition to propelling them quickly, serves to shade their bodies from the sun. Sir John eventually reaches the lands around India with their various and exotic religions — some worship snakes (lines 1586–87) and others allow themselves to be crushed under the wheels of a chariot bearing their idol (lines 1655–59). After a discussion of the roundness of the world (lines 1687–1778) and mention of additional marvels, such as men and women with heads like dogs (lines 1854–68) or others with both male and female genitals (lines 1892–95), Sir John arrives in China and describes the almost unimaginable wealth, luxury, and pomp at the court of the Great Khan with a full account of the realm’s particular laws and customs (lines 1968–2017, 2100 ff.). As he continues on, Sir John encounters additional strange beings and practices, and, after a warning about the dangers that Jews will pose at the time of the Antichrist (lines 2366–82), he describes Prester John (an emperor and a priest), who though allied with the Khan is a Christian, but not a Catholic (lines 2392 ff.). Near the end of his Book, Sir John describes a kind of ideal society: that of the Brahmins and Synoplians, who even though they lack Christian revelation follow its essential precepts by natural law and whose faith, simple life, and love and charity toward one another make them beloved of God (lines 2573–2637). After observing gold-digging ants in Ceylon, passing by but not being able to visit the Earthly Paradise (lines 2681–2706), and describing the Tibetan practice by which a son honors his dead father by offering his body to birds and the flesh of his head to special friends (lines 2763–83), Sir John, having circumnavigated the earth, returns home to England to rest in his old age.

“Debate about the identity of the author also continues. Some popular English opinion still holds out for Sir John Mandeville — there is a plaque in his honor in St. Albans Cathedral and a Fleet Street veteran has recently taken up his cause — but scholars have also suggested other candidates, including Jean d’Outremeuse, a notary of Liège, and Brother Jean de Long of the Benedictine Abbey Church of St. Bertin. It seems unlikely that we shall ever be certain about the authorship of the Book. Indeed, applying the term author to this work is imprecise and somewhat misleading. Obviously someone first assembled the materials we know as The Book of John Mandeville, but, as has been noted, he borrowed rather than created most of those contents. Rather than a wholly original author, Mandeville is best considered a compiler, one who collects and rearranges the writings of others into a new form.

Just as whoever first put together the Book combined and rewrote previous texts, the work he produced proved equally malleable, for it was itself, in turn, adapted, abridged, and supplemented by later redactors in a variety of ways including but not limited to the kinds of alterations to the narrative voice we have already discussed. What we call the Book resists precise definition because it differs from version to version as well as from text to text within a particular version. The Book of John Mandeville refers less to a single stable entity than to what Iain Higgins, in the most illuminating current study of the work, has called a “multi-text.” The original composition of the Book did not fix the work because it was so quickly and variously transformed by those who received it.” (Kohanski and Benson, The Book of John Mandeville: Introduction (2007)). (Inventory #: 5104)