Carousel content with 1 slides.

A carousel is a rotating set of images, rotation stops on keyboard focus on carousel tab controls or hovering the mouse pointer over images. Use the tabs or the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide.

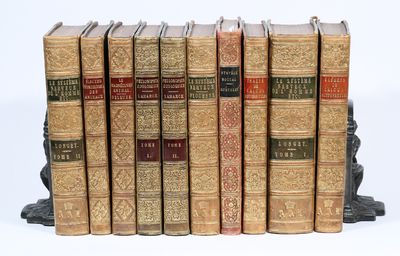

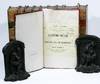

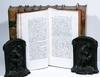

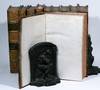

signed first edition Three quarters calf gilt

1825 · np

by LOVELACE, ADA [owned by]

np: np, 1825. Mixed editions. Three quarters calf gilt. Very Good. IMPORTANT BOOKS FROM ADA LOVELACE’S LIBRARY, INCLUDING TWO CALCULUS BOOKS AND A HIGHLY SIGNIFICANT PRESENTATION COPY TO HER: In demonstrating the breadth of Lovelace’s intellectual curiosity and revealing the connective tissue of her mind, this collection of books forms a solid intellectual core on which future academic consideration of Lovelace’s thought can build. In an era where mathematics and analytics were male-dominated professions, Ada Lovelace overcame the sexism of her time to become an innovator and a pioneer whose contributions and ideas laid the groundwork for the modern (truncated) computer revolution. The only legitimate child of poet Lord Byron and Lady Byron, Lovelace was committed to original thinking and creativity. As a teenager she worked closely with her tutor, the accomplished scientist Mary Somerville, who both inspired Ada to broaden her own acquaintance with the sciences and also introduced her to Charles Babbage, who nicknamed Lovelace the "Enchantress of Number." (Smith). Shortly after her marriage to William King in 1835, Lovelace declared she was a “Bride of Science” and accelerated her studies. Indeed so active was her mind and so intense her studies, that Augustus De Morgan (the famed scientist and logician who acted as Ada’s advanced-mathematics tutor), warned Lovelace’s mother that Ada was at risk of physical and psychological destruction – a warning which Lovelace herself brushed aside, instead proclaiming that “my intellect will keep me alive, and active.” (Winter, 220).

Poetry and Analysis were “indissolubly” interwoven in Lovelace’s life, and this imaginative capacity decidedly set her apart from the more narrowly-focused utilitarian minds of her age. For Lovelace, mathematics constituted “the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the natural world, and it allows us to portray the changes of mutual relationship” that unfold within creation. (Isaacson, 17). Living as she did in the intersection between science and poetry, Lovelace could both conceive and extrapolate the possibilities and applications of science, and she could effectively generate and communicate sophisticated ideas in a way that many in her field could not. Thus Lovelace could see beauty and the future in the metal hardware of a calculating engine, whereas most others – including Babbage himself – saw only an efficient means for simplifying the immediate computational tasks of life.

In 1842-43 Lovelace translated Luigi Menabrea’s article about Babbage’s Analytical Engine, the first published statement about the invention. Very significantly, Lovelace supplemented her translation with an elaborate set of “Notes” which not only contained important remarks about the machine’s programmability but also explicitly wrote out an algorithm to compute Bernoulli numbers, which many consider the first computer program. In these “Notes” Lovelace wrote that computers could be programmed to follow any symbolic notations, including musical and artistic ones, and to “weave algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” Lovelace also posed questions about Babbage’s Analytical Engine and considered how individuals and society could use technology as a collaborative instrument, a visionary idea that did not become reality until Alan Turing’s era.

Much of Lovelace’s commentary and analysis was inspired by the texts that she studied, many of which are included in this unique collection. Lovelace is known to have read and analyzed the works of the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quételet. This copy of Du Système Social et des Lois qui les Régissent was inscribed by Quételet to Lady Lovelace and has numerous marginal lines emphasizing passages, almost certainly in Lovelace’s own hand. In addition to the Lubbe and Boucharlat mathematical books offered here, this collection of Lovelace’s personal and reference library also includes Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s early volumes about evolution, Joseph-Philippe-François Deleuze’s writings about animal magnetism, Carlo Matteucci’s work on the electrical properties of animal tissue and published research on experimental physiology and the autonomic nervous system by Flourens and Longet, which includes the pencil inscription “Lovelace”, in what is very likely (and logically) in her own hand. These volumes demonstrate the breadth of Lovelace’s intellectual curiosity and reveal the context and connective tissue through which she made many of her discoveries. According to Lovelace, “[math] constitutes the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the natural world, and it allows us to portray the changes of mutual relationship” that unfold in creation. (Isaacson, 17).

The books in Lovelace’s library:

Lovelace’s translation of Menabrea’s article was her only lifetime scientific published work (though see our note regarding Quetelet, below), and deeper insight into Lovelace’s mind – and the intellectual background of her “Notes” – is perhaps only to be attained through a knowledge of the books she read. No catalogue of Lovelace’s library was however made, and very few of the books she owned are known to have survived. Indeed the present offering may very well be the only remaining opportunity to acquire books from Lovelace’s personal library.

The books offered here very certainly reflect the intellectuality and tendencies of Lovelace’s mind. These titles evidence her broad scientific interests -- with the mathematical, biological, and human social sciences all being exampled in the collection. In addition to a highly important copy of Adolphe Quetelet’s Du Système Social et des Lois qui les Régissent, the remaining titles include an important group of texts relating to Lovelace’s investigations into the nervous system and the brain – an academically under-explored area of Lovelace’s scientific researches – as well as a famous work on the nascent field of Evolution, and of course two books on the Calculus. Ranging from Longet’s anatomical study of the human nervous system and Flourens’ experimental researches on the nervous system – this latter work including the pencil inscription “Lovelace” in what appears to be Ada’s own hand – to Matteucci’s work on the electrical properties of animal tissue and Deleuze’s writings about animal magnetism, these biological works give concrete substance to Lovelace’s neurological investigations, an area of Lovelace’s interest that has been pointed at, but not yet formally studied. The two volumes of Lamarck’s 1850 edition of Philosophie Zoologique testify to Lovelace’s (not surprising) interest in the emerging debate about evolution; and her copy of Lubbe’s treatise on the Calculus is not only a fine representative specimen of her mathematical learning, but it is also probably a text she in fact studied under the tutelage of Mary Somerville.

Lovelace’s copy of Quetelet’s 1848 Du Système Social et des Lois qui les Régissent is deserving of special attention. Not only is this book a signed presentation copy from Quetelet to “Lady Lovelace,” but it also contains a good many emphatic marginal markings, almost certainly in Lovelace’s own hand. One of Quetelet’s most important books, this work pioneered the application of statistics to social phenomena and is one of the foundational texts of modern sociological science. Quetelet was arguably the greatest statisticians of his day; and as one of England’s first and leading statisticians, Babbage both knew him and introduced Lovelace to his work. Both Babbage and Lovelace recognized that statistical calculation was an ideal application of Babbage’s mechanical engines, and we in fact see such thinking reflected in Lovelace’s 1843 published “Notes” about the Analytical Engine. Very remarkably, Lovelace’s own unique relationship to Quetelet is immortalized in a footnote she appended to her husband’s 1848 article reviewing the different mathematical theories correlating climate and crop yield, in which she explicitly advocated for the adoption of Quetelet’s statistically-based mathematical theory (Hollings, Martin, Rice). And this footnote – apparently one of only two other lifetime published scientific observations by Lovelace outside of her 1843 “Notes” – undoubtedly functioned as a basis for Quetelet presenting Lovelace a copy of his book. Lovelace’s copy of Quetelet’s text is unknown to scholarship, and deciphering the meaning and intent of her likely marginal delineations remains an Intriguing project for future scholarship.

List of books, in custom Lovelace library bindings:

Deleuze, Joseph-Philippe-François. Instruction Pratique Sur Le Magnétisme Animal, 1825.

Lubbe, Samuel Ferdinand. Traité De Calcul Différentiel et De Calcul Intégral, 1832.

Boucharlat, Jean Louis. Élémens De Calcul Différentiel et De Calcul Intégral, Fifth Edition, 1838.

Flourens, Marie-Jean-Pierre. Recherches Expérimentales... Du Système Nerveux..., 1842.

Longet, François Achille. Anatomie et Physiologie du Système Nerveux de l’Homme et des Des Animaux Vertébrés, 2 Vol., 1842.

Matteucci, Carlo. Traité Des Phénomènes Électro-Physiologiques Des Animaux, 1844.

Quételet, Adolphe. Du Système Social Et Des Lois Qui Les Régissent, 1848.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste. Philosophie Zoologique, 2 Vol., New Edition, 1850.

Octavos, contemporary half calf, slightly rubbed, gilt spines, Eight titles in ten volumes, all from the library of Ada Lovelace. Seven volumes with blind-stamps of East Horsley Tower on titles and front endpapers, Four volumes with gilt initials AAL at tail of spines.

AN EXCEEDINGLY RARE AND IMPORTANT SET: IT IS UNLIKELY ANY OTHER VOLUMES FROM LOVELACE'S LIBRARY WILL COME TO MARKET.

References:

Erik Gregersen. “Ada Lovelace: British Mathematician,” Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2021.

Christopher Hollings, Ursula Martin and Adrian Rice. Ada Lovelace: The Making of a Computer Scientist. Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2018.

Walter Isaacson. The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014.

Nate Smith. “The Enchantress of Number,” Inside Adams. Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/. 7 October 2019.

Dorothy Stein. Ada: A Life And A Legacy. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1987.

Alison Winter. A Calculus of Suffering: Ada Lovelace and the Bodily Constraints on Women's Knowledge in Early Victorian England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. (Inventory #: 2912)

Poetry and Analysis were “indissolubly” interwoven in Lovelace’s life, and this imaginative capacity decidedly set her apart from the more narrowly-focused utilitarian minds of her age. For Lovelace, mathematics constituted “the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the natural world, and it allows us to portray the changes of mutual relationship” that unfold within creation. (Isaacson, 17). Living as she did in the intersection between science and poetry, Lovelace could both conceive and extrapolate the possibilities and applications of science, and she could effectively generate and communicate sophisticated ideas in a way that many in her field could not. Thus Lovelace could see beauty and the future in the metal hardware of a calculating engine, whereas most others – including Babbage himself – saw only an efficient means for simplifying the immediate computational tasks of life.

In 1842-43 Lovelace translated Luigi Menabrea’s article about Babbage’s Analytical Engine, the first published statement about the invention. Very significantly, Lovelace supplemented her translation with an elaborate set of “Notes” which not only contained important remarks about the machine’s programmability but also explicitly wrote out an algorithm to compute Bernoulli numbers, which many consider the first computer program. In these “Notes” Lovelace wrote that computers could be programmed to follow any symbolic notations, including musical and artistic ones, and to “weave algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” Lovelace also posed questions about Babbage’s Analytical Engine and considered how individuals and society could use technology as a collaborative instrument, a visionary idea that did not become reality until Alan Turing’s era.

Much of Lovelace’s commentary and analysis was inspired by the texts that she studied, many of which are included in this unique collection. Lovelace is known to have read and analyzed the works of the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quételet. This copy of Du Système Social et des Lois qui les Régissent was inscribed by Quételet to Lady Lovelace and has numerous marginal lines emphasizing passages, almost certainly in Lovelace’s own hand. In addition to the Lubbe and Boucharlat mathematical books offered here, this collection of Lovelace’s personal and reference library also includes Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s early volumes about evolution, Joseph-Philippe-François Deleuze’s writings about animal magnetism, Carlo Matteucci’s work on the electrical properties of animal tissue and published research on experimental physiology and the autonomic nervous system by Flourens and Longet, which includes the pencil inscription “Lovelace”, in what is very likely (and logically) in her own hand. These volumes demonstrate the breadth of Lovelace’s intellectual curiosity and reveal the context and connective tissue through which she made many of her discoveries. According to Lovelace, “[math] constitutes the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the natural world, and it allows us to portray the changes of mutual relationship” that unfold in creation. (Isaacson, 17).

The books in Lovelace’s library:

Lovelace’s translation of Menabrea’s article was her only lifetime scientific published work (though see our note regarding Quetelet, below), and deeper insight into Lovelace’s mind – and the intellectual background of her “Notes” – is perhaps only to be attained through a knowledge of the books she read. No catalogue of Lovelace’s library was however made, and very few of the books she owned are known to have survived. Indeed the present offering may very well be the only remaining opportunity to acquire books from Lovelace’s personal library.

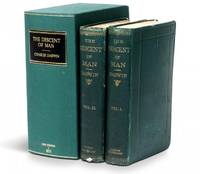

The books offered here very certainly reflect the intellectuality and tendencies of Lovelace’s mind. These titles evidence her broad scientific interests -- with the mathematical, biological, and human social sciences all being exampled in the collection. In addition to a highly important copy of Adolphe Quetelet’s Du Système Social et des Lois qui les Régissent, the remaining titles include an important group of texts relating to Lovelace’s investigations into the nervous system and the brain – an academically under-explored area of Lovelace’s scientific researches – as well as a famous work on the nascent field of Evolution, and of course two books on the Calculus. Ranging from Longet’s anatomical study of the human nervous system and Flourens’ experimental researches on the nervous system – this latter work including the pencil inscription “Lovelace” in what appears to be Ada’s own hand – to Matteucci’s work on the electrical properties of animal tissue and Deleuze’s writings about animal magnetism, these biological works give concrete substance to Lovelace’s neurological investigations, an area of Lovelace’s interest that has been pointed at, but not yet formally studied. The two volumes of Lamarck’s 1850 edition of Philosophie Zoologique testify to Lovelace’s (not surprising) interest in the emerging debate about evolution; and her copy of Lubbe’s treatise on the Calculus is not only a fine representative specimen of her mathematical learning, but it is also probably a text she in fact studied under the tutelage of Mary Somerville.

Lovelace’s copy of Quetelet’s 1848 Du Système Social et des Lois qui les Régissent is deserving of special attention. Not only is this book a signed presentation copy from Quetelet to “Lady Lovelace,” but it also contains a good many emphatic marginal markings, almost certainly in Lovelace’s own hand. One of Quetelet’s most important books, this work pioneered the application of statistics to social phenomena and is one of the foundational texts of modern sociological science. Quetelet was arguably the greatest statisticians of his day; and as one of England’s first and leading statisticians, Babbage both knew him and introduced Lovelace to his work. Both Babbage and Lovelace recognized that statistical calculation was an ideal application of Babbage’s mechanical engines, and we in fact see such thinking reflected in Lovelace’s 1843 published “Notes” about the Analytical Engine. Very remarkably, Lovelace’s own unique relationship to Quetelet is immortalized in a footnote she appended to her husband’s 1848 article reviewing the different mathematical theories correlating climate and crop yield, in which she explicitly advocated for the adoption of Quetelet’s statistically-based mathematical theory (Hollings, Martin, Rice). And this footnote – apparently one of only two other lifetime published scientific observations by Lovelace outside of her 1843 “Notes” – undoubtedly functioned as a basis for Quetelet presenting Lovelace a copy of his book. Lovelace’s copy of Quetelet’s text is unknown to scholarship, and deciphering the meaning and intent of her likely marginal delineations remains an Intriguing project for future scholarship.

List of books, in custom Lovelace library bindings:

Deleuze, Joseph-Philippe-François. Instruction Pratique Sur Le Magnétisme Animal, 1825.

Lubbe, Samuel Ferdinand. Traité De Calcul Différentiel et De Calcul Intégral, 1832.

Boucharlat, Jean Louis. Élémens De Calcul Différentiel et De Calcul Intégral, Fifth Edition, 1838.

Flourens, Marie-Jean-Pierre. Recherches Expérimentales... Du Système Nerveux..., 1842.

Longet, François Achille. Anatomie et Physiologie du Système Nerveux de l’Homme et des Des Animaux Vertébrés, 2 Vol., 1842.

Matteucci, Carlo. Traité Des Phénomènes Électro-Physiologiques Des Animaux, 1844.

Quételet, Adolphe. Du Système Social Et Des Lois Qui Les Régissent, 1848.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste. Philosophie Zoologique, 2 Vol., New Edition, 1850.

Octavos, contemporary half calf, slightly rubbed, gilt spines, Eight titles in ten volumes, all from the library of Ada Lovelace. Seven volumes with blind-stamps of East Horsley Tower on titles and front endpapers, Four volumes with gilt initials AAL at tail of spines.

AN EXCEEDINGLY RARE AND IMPORTANT SET: IT IS UNLIKELY ANY OTHER VOLUMES FROM LOVELACE'S LIBRARY WILL COME TO MARKET.

References:

Erik Gregersen. “Ada Lovelace: British Mathematician,” Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2021.

Christopher Hollings, Ursula Martin and Adrian Rice. Ada Lovelace: The Making of a Computer Scientist. Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2018.

Walter Isaacson. The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014.

Nate Smith. “The Enchantress of Number,” Inside Adams. Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/. 7 October 2019.

Dorothy Stein. Ada: A Life And A Legacy. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1987.

Alison Winter. A Calculus of Suffering: Ada Lovelace and the Bodily Constraints on Women's Knowledge in Early Victorian England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. (Inventory #: 2912)

![Autograph Letter Signed [ALS] to Joë Bousquet](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/064/316/1693316064.0.m.jpg)