1931 · Chapel Hill, North Carolina

by [Huges, Langston]

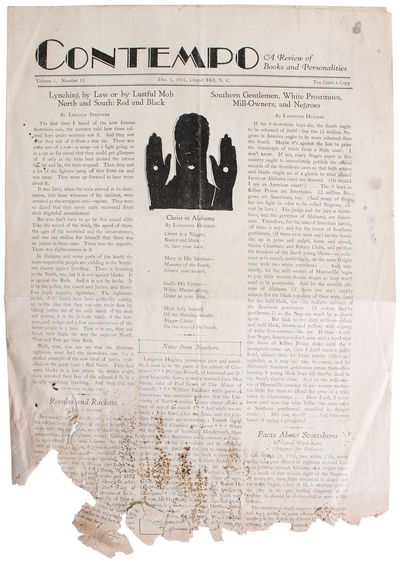

Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Contempo, Ltd, 1931. Fair. About 17” x 12½” (issued). Newsprint. Pp. 4. Fair: bottom tattered, with about 3” of loss and susceptible to more; moderate foxing to lower quarter; some small stains and spotting.

This is an issue of Contempo, a fairly well-known North Carolina periodical, invaluable for its distinction of holding the first printed appearance of Langston Hughes' controversial poem “Christ in Alabama.”

Hughes wrote the poem in 1931 in response to the infamous Scottsboro case, in which two white women falsely accused nine young Black men of rape. He sent it to Contempo that October, and the (truncated)

This is an issue of Contempo, a fairly well-known North Carolina periodical, invaluable for its distinction of holding the first printed appearance of Langston Hughes' controversial poem “Christ in Alabama.”

Hughes wrote the poem in 1931 in response to the infamous Scottsboro case, in which two white women falsely accused nine young Black men of rape. He sent it to Contempo that October, and the (truncated)

![Souvenir. 1901-'02. The City of... Houston, Texas [Cover title]](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/073/604/1693604073.0.m.jpg)