first edition full leather binding

1598, 1613 · Frankfurt, Heidelberg

by Gesner, Conrad

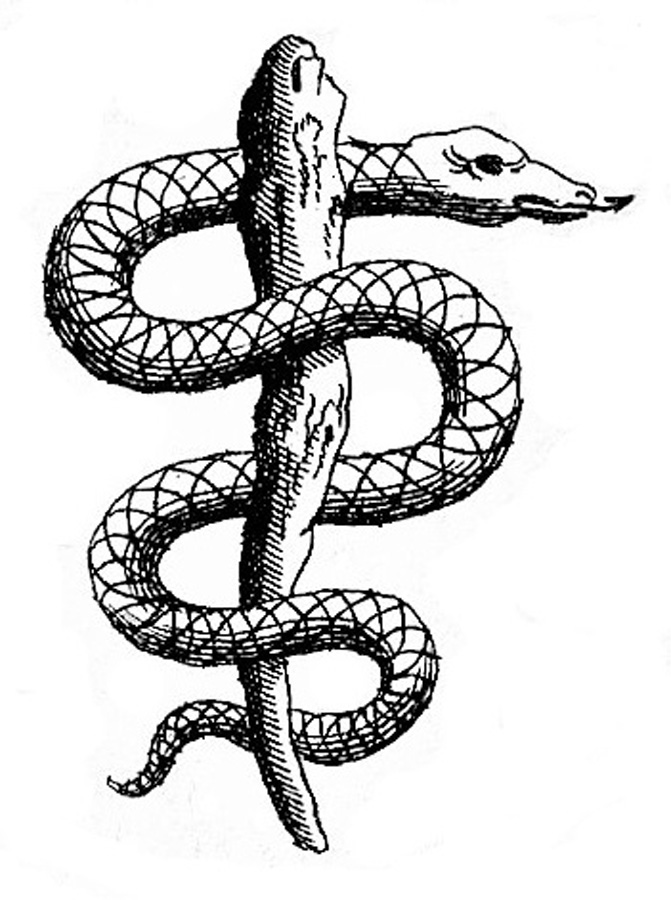

Frankfurt, Heidelberg: Johann Saur, Johan Lancellot, 1598, 1613. (De piscium first Latin edition 1558, De serpentibus first Latin edition 1587). 1598 MAGNIFICENT FOLIO VOLUME OF GESNER'S LANDMARK NATURAL HISTORY OF MARINE LIFE AND SERPENTS ILLUSTRATED WITH OVER 600 VIVID WOODCUTS. 23x36 cm folio hardcover, later full leather binding, rebacked with spine with raised bands, gilt compartments, gilt title to red leather spine label, green patterned endpapers with large armorial bookplate to front paste-down, armorial bookplate of Diana Russell to front free endpaper, [vi], 202 leaves, [iv], 72 leaves, (includes "De Scorpione", [62]-72, which has special title page). Wear to covers, binding tight, light browning to page edges, scattered light foxing, a few expert paper repairs not affecting woodcuts, marginal ink notation in contemporary hand (p 171 verso), overall very good copy of early German translations of the last 2 volumes of Gesner's landmark Historia animalium first published in Latin ~50 years earlier. Woodcuts of fish, crustaceans, echinoderms, molluscs, turtles--many with details accurately depicting living species, but also including a number representing monstrous mythical creatures from earlier texts. GARRISON-MORTON 280: GESNER, Conrad. (1516-1565) Historia animalium. First editions, 5 vols. Tiguri, apud C. Froschouerum, 1551-1587. Gesner was a man of great industry. His Historia animalium is considered one of the starting points of modern zoology; it contains 4,500 pages and nearly 1,000 woodcuts, some being by Albrecht Durer. It includes the names of all the known animals in the ancient and modern languages, together with a mass of information regarding them. Portions of this work were translated by Edward Topsel as The historie of fourfooted beasts. London, 1658. Described by Richard Ellis in Natural Histories: "Conrad Gessner (a.k.a. Konrad Gesner, Conradus Gessnerus, etc.) was born in Zurich on March 26, 1516, and died there on December 13, 1565. His five-volume Historia animalium {Histories of the animals) was published between 1551 and 1558, and is considered the beginning of modern zoology. The first volume is an illustrated work on live-bearing four-footed animals (mammals). Volume 2 is on egg-laying quadrupeds (crocodiles and lizards), and Volume 3 is on birds, Volume 4 is on fish and other aquatic animals, and a Volume 5 on serpents (snakes and scorpions) was published posthumously (both offered here). The Historia animalium was Gessner's magnum opus, and is an attempt to fashion a connection between the ancient knowledge of the animal world and Renaissance science. Gessner's monumental work is based on the Old Testament, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin sources. and is compiled from folklore as well as ancient and medieval texts, as many of the animals' names appear in Greek and Hebrew. For living animals, he incorporated the inherited knowledge of ancient naturalists like Aristotle, Pliny, and Aelian, and for information on mythical animals-which he usually identified as such-he drew from folktales, myths, and legends, some of which came from material in the Physiologus, a book of animal legends that was produced in Alexandria in the second century. Though Gessner sought to distinguish facts from folklore, his encyclopedic work also includes mythical creatures and imaginary beasts, mingled with unknown animals from the New World, the Far North (the publication coincided with the early searches for the Northeast and Northwest Passages), and newly discovered animals of the Indies. Where appropriate, Gessner documented the uses of animals and animal products in medicine and nutrition, alongside their places in history, literature, and art. Because the Historia animalium included illustrations-often of animals in their natural habitat-Gessner's approach to natural history was most unusual for sixteenth-century readers. Gessner acknowledges one of his main illustrators as Lucas Schan, an artist from Strasbourg, and also identifies the pictorial contributions of Olaus Magnus, Guillaume Rondelet, Pierre Belon, Ulisse Aklrovandi, and Albrecht Durer. Gessner's sea monkey illustration was taken directly from one drawn by Johannes Kentmann, a Dresden physician and naturalist who also identified it as Simia marina. As reproduced here, Gessner's Simia marina shows some resemblance to a seal (four "flippers"); a shark (a lot of teeth); an otter (four flippers and a long tail); and some sort of a fish (but there are no gills). Because Gessner wrote, ''Nan pisces quid haec. Sed bestia cartilaginea [Not fishes as such but cartilaginous beasts]," he obviously meant it to be a chimaera, a cartilaginous fish that is neither exactly a shark nor exactly a bony fish. In Greek mythology, the chimaera was a firebreathing monster with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the tail of a serpent. Despite its sometimes enigmatic inclusions, Historia animalium forms the solid basis for the study of ancient and modern zoology. Many of the known creatures (and several of the unreal ones) are meticulously described and illustrated in its five volumes." LISTED IN Printing and the Mind of Man (1963). PROVENANCE: DIANA RUSSELL, Duchess of Bedford, née Lady Diana Spencer (1710 – 1735), was a member of the Spencer family, chiefly remembered because of an unsuccessful attempt to arrange a marriage for her with Frederick, Prince of Wales. Orphaned by the age of 6, Lady Diana joined the household of her maternal grandmother, Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, who arranged a secret marriage between Lady Diana and Prince Frederick, King George II's eldest son and heir apparent to the throne. When the scheme was thwarted by Prime Minister Robert Walpole, Lady Diana was married to Lord John Russell, later 4th Duke of Bedford. The Duchess of Bedford died of tuberculosis at the age of 25.

(Inventory #: 1549)