1772 · Turin

by JUDGMENT DAY —

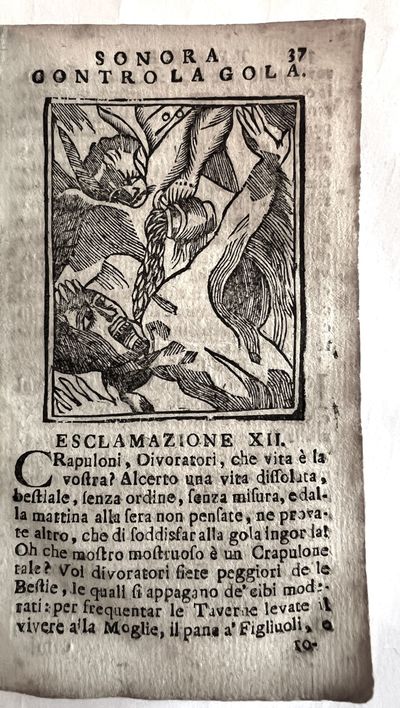

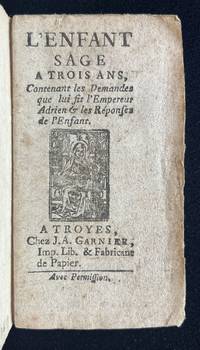

Turin: nella stamperia [Gerardo?] Giuliano, 1772. 12mo (151 x 85 mm). 180 pages. 26 half-page woodcuts printed from 23 blocks, of which 22 showing tormented souls in Hell and one a memento mori; five smaller woodcuts: title cut of St. Michael (printer’s device?), St. Francis receiving the stigmata, the Trinity with spheres of the cosmos, a skull and crossbones, and the Crucifixion; a few type ornaments. (Lower corners of fols. B1 and B2 torn with loss to a few words on B2v; softened, some corners creased, light foxing.) 20th-century quarter parchment and block-printed paper covered boards (scrape to lower cover). Provenance: “Ex libris Sac. J. Henry,” (truncated)