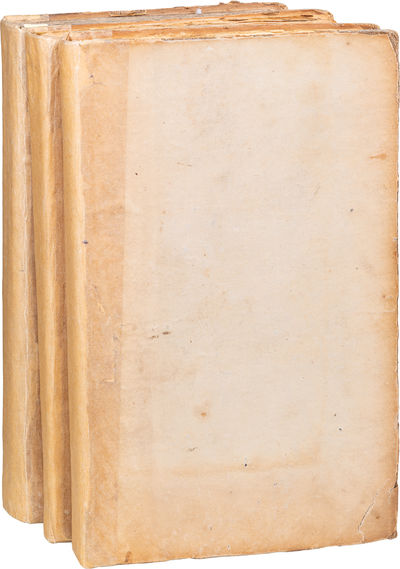

first edition

1804 · London

by Hamilton, Elizabeth

London: Printed by R. Cruttwell for G. and J. Robinson, 1804. First Edition. Very good. An astute novel set in Rome during the Ist century where the ruling axiom was to learn quickly and early that the most useful aspect of a principle is that it can always be sacrificed to expediency. Original buff-white boards, uncut, neatly rebacked with matching paper in the same style as the original spines. There's a mend to the upper corner of vol. 1, light soiling to the boards, rubbing to the extremities titles, internally clean and beautiful with only a few spots of foxing throughout. And, though the half-titles are integral, they are not included in the pagination (truncated)