1800 · Rome

by [FOOD/ROME/ECONOMY]. Sinibaldi, Cesare Marchese

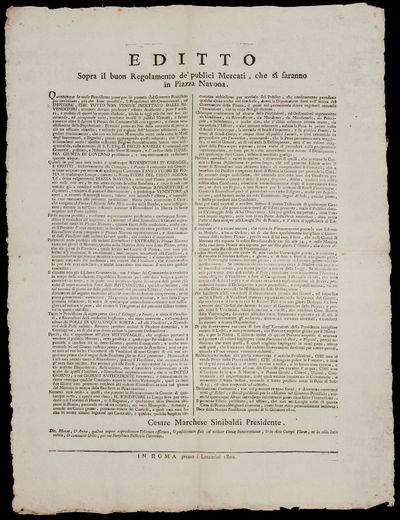

Single broadsheet [60 x 44.5 cm], folded. A very good copy.

A rare survival of such an ephemeral piece (unrecorded on ICCU): a large broadside issued during the nine-month occupation of Rome following the fall of the Roman Republic, and proclaiming a complete revision of the running of the city's public market to prevent "hoarders and scalpers" from inflating food prices beyond the means of the "most sensitive" members of the populace during this tumultuous period.

The edict instructs, for example, all retailers of vegetables and fruits to arrange contracts exclusively during daylight hours, and only under their official banners; any retailers (truncated)

A rare survival of such an ephemeral piece (unrecorded on ICCU): a large broadside issued during the nine-month occupation of Rome following the fall of the Roman Republic, and proclaiming a complete revision of the running of the city's public market to prevent "hoarders and scalpers" from inflating food prices beyond the means of the "most sensitive" members of the populace during this tumultuous period.

The edict instructs, for example, all retailers of vegetables and fruits to arrange contracts exclusively during daylight hours, and only under their official banners; any retailers (truncated)