This past April, the biggest news to hit the antiquarian book trade in roughly 400 years became public: my colleagues Dan Wechsler and George Koppelman, booksellers in New York City, unveiled a copy of a sixteenth century dictionary which could, quite plausibly, have once belonged to William Shakespeare — complete with annotations possibly in the bard’s hand and many tantalizing, if ultimately circumstantial, linguistic and stylistic links to his plays. I’ll leave it to better minds than mine to make a final determination regarding the dictionary’s provenance. Wechsler and Koppelman have laid out an entire volume of compelling evidence in their just-published book, Shakespeare’s Beehive (a copy of which I’ve just ordered); the Folger Shakespeare Library, the New Yorker, and numerous book bloggers have already begun weighing in, and I’m sure many more scholarly voices will be added to the fray over the coming months and years. I hope it’s years, not months. I hope it’s real, real enough at least to merit many years of scholarship – I really, really do.

But regardless what this volume turns out to be, whether the hundreds of annotations on its 400-year-old pages turn out to be the long-sought mainline to Shakespeare’s creative process or just a host of happy coincidences, the whole wonderful escapade serves to remind me that this pursuit my colleagues and I are engaged in, which so many days feels like little more than a glorified exercise in rag-picking, has resonances far beyond the little world of booksellers, librarians, and collectors we imagine, on our worst days, is the only one we inhabit. For books, to revisit Milton’s adage, “are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are…” *

So it goes with Shakespeare’s dictionary; and so, on a somewhat less magnificent scale, did it go for a handsome American Bible which I recently had the good fortune to shepherd from the floor of the New York Book Fair to my friends in the Special Collections Division of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Now, this wasn’t just any Bible: it was President Andrew Jackson’s family Bible, presented to him by the publisher in an elaborate gilt-stamped morocco binding on the occasion of his second inaugural. Through a fairly predictable series of circumstances – apathy, the contempt bred of familiarity, and the temporary impecuniousness of a Jackson descendant – the Bible had become separated from the Jackson family nearly 100 years ago and made its way, finally, through the wilderness, into the hands of a reputable bookseller; thence to the New York Book Fair; thence to me (reputable or not – you make the call).

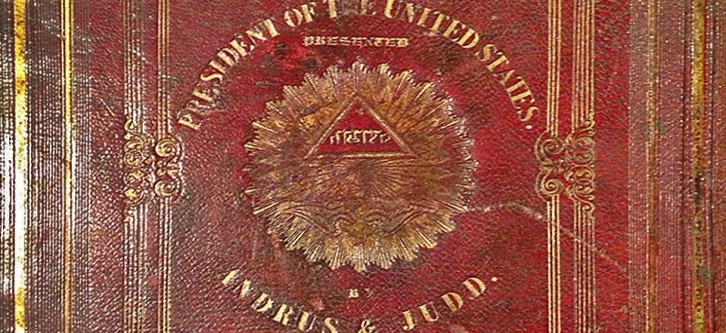

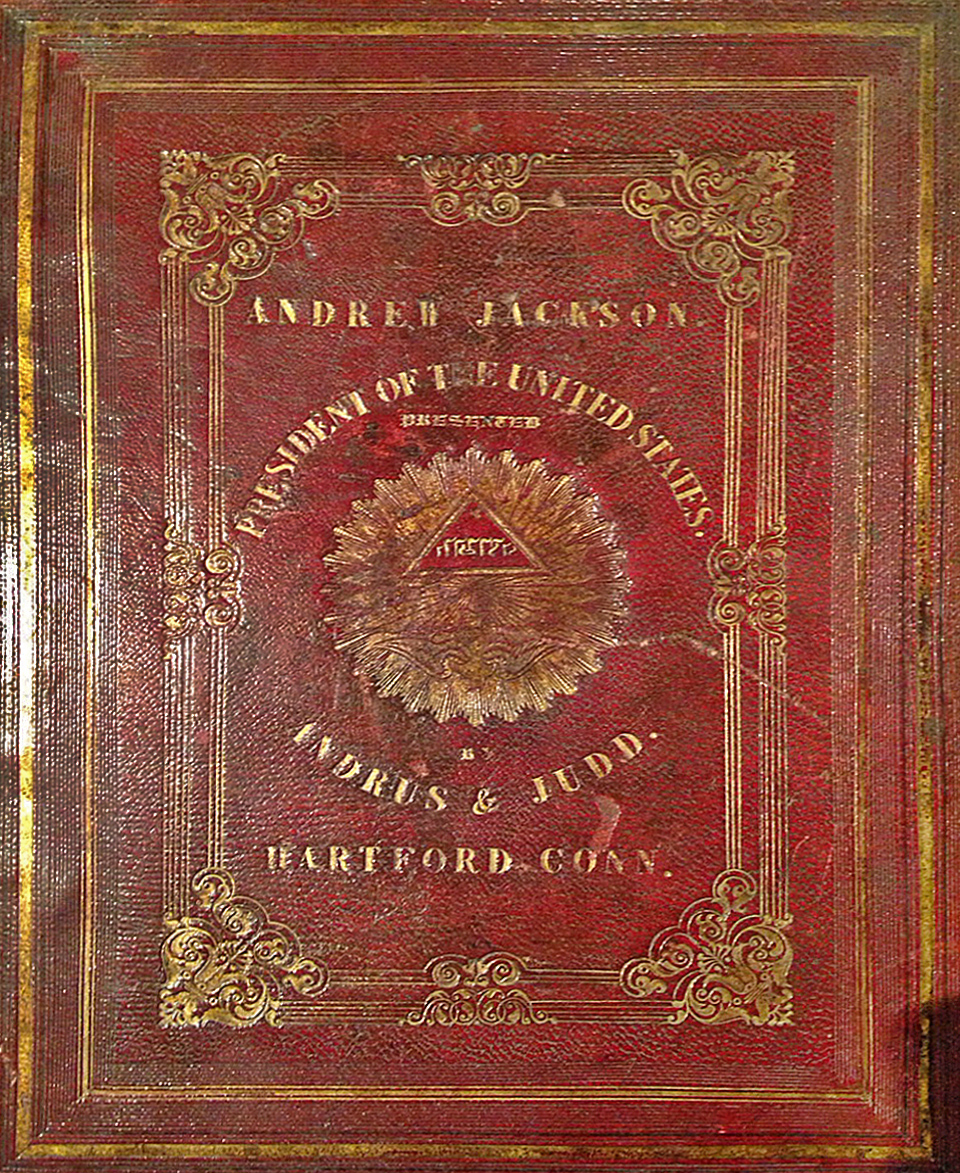

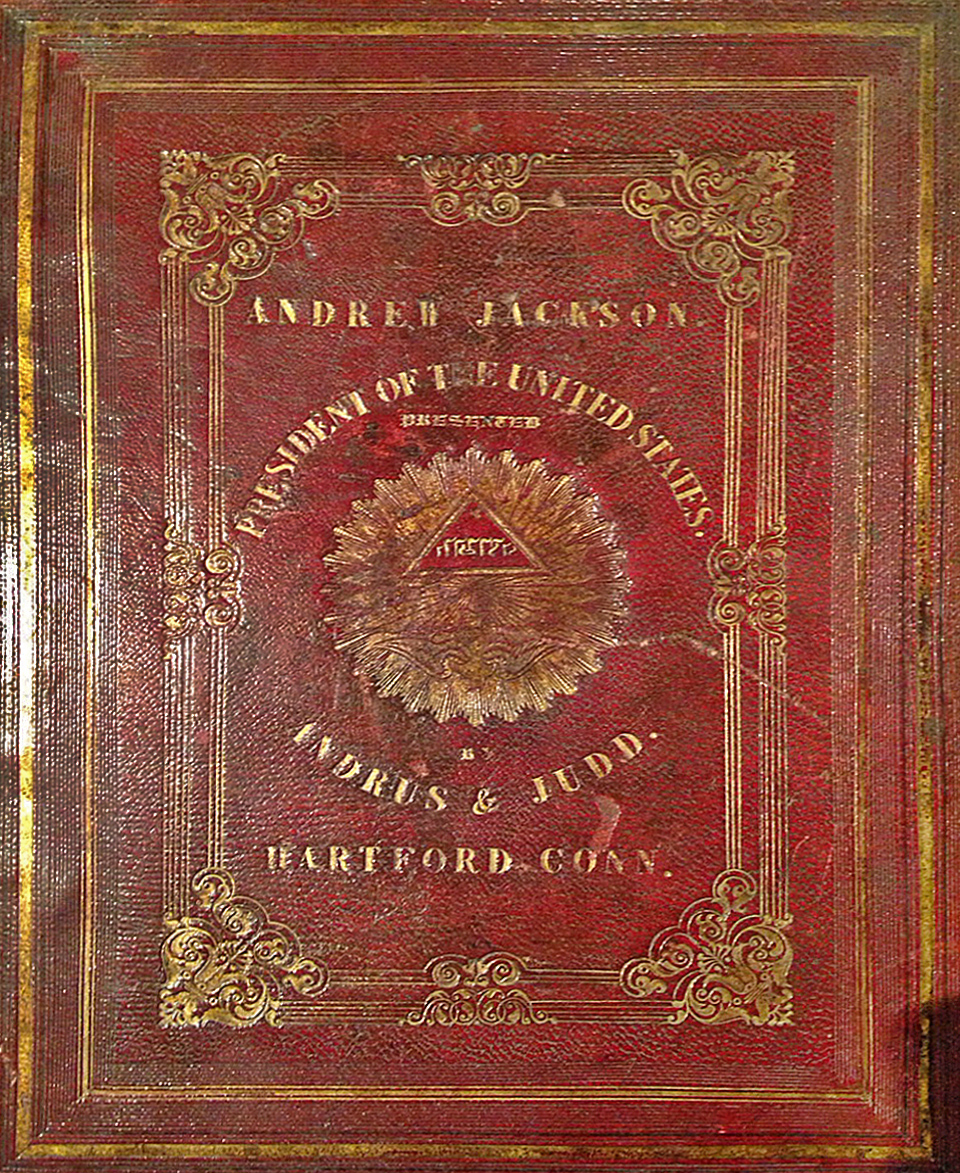

Here’s what it looks like today:

The story unfolded quickly, and since it redounds only minimally to my credit (though a great deal to others’), I’ll share it briefly. It was early on day one of the New York Book Fair. I’d had a fairly miserable set-up (for those who may not be familiar with the realpolitik of antiquarian book fairs, many dealers – I’m no exception – do up to 90% of their business before the show even opens. As of Friday morning, I’d done just about enough to pay for my first night’s bar tab. Not good.), and I was sulking in my booth when my phone rang. On the other end was my friend Steve Smith, whose day job is Dean of Libraries at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, though for one week a summer he also joins me on the faculty of the Colorado Antiquarian Book Seminar; we also share an appreciation for traditional Appalachian string band music, fine printing, and shaggy-dog stories with awful punch lines — needless to say, we’re fast friends. Steve had heard a rumor, just a vague rumor, that somewhere on the floor of the New York Book Fair — “I think it might be in the Serendipity booth,” he told me — a Bible once belonging to Andrew Jackson had been spotted for sale. “Would you track it down for me?,” he asked, “and give it the once-over?”

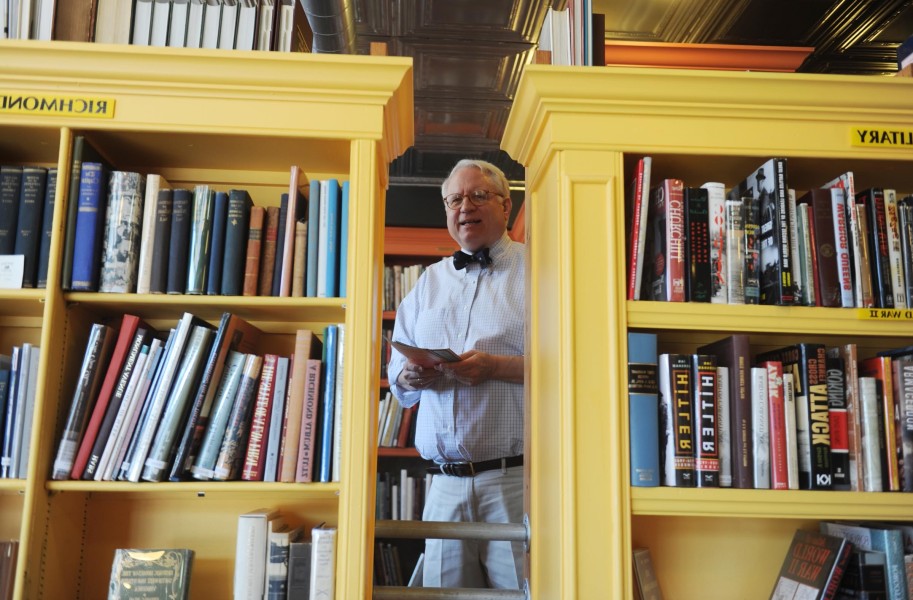

Would I! Sitting in my own booth had become torture at this point, and I was glad for any opportunity to get up and wander around – this, despite the fact that Peter Howard’s Serendipity Books hadn’t had a booth at the New York Fair in at least ten years, and Peter himself passed away three years ago now. Despite that red herring It didn’t take me long to track down the object of Steve’s desire — among my Americanist colleagues, Jackson’s Bible had apparently been creating something of a buzz all during set-up, though no one had managed to buy it yet, or to sell it over the phone. Happily, the Bible was in the booth of two of my best friends in the book business, Nick and Ellen Cooke of Black Swan Books in Richmond (that’s Nick down below, peeking through the stacks of his lovely shop, which is made lovelier still by the presence of Ellen, his wife, who is not in this picture nor, sadly and mysteriously, to be found in any other image of Black Swan I’ve been able to get my hands on. She is not, for the record, to the best of my knowledge, a ghost.). These are folks who’ve done me many a good turn over the years. Now it was my turn to do one for them (the antiquarian book business depends for its continuance, to a substantial degree, on good turns).

Nick and Ellen are the real heroes of this story. They’re the ones to whom Jackson’s Bible was first brought, in a woeful state of preservation – covers and spine detached, binding loose, but magically still complete, including the genealogical register completed by hand by Jackson’s daughter-in-law – some time late last year. They’re the ones who did the research establishing that the Bible was, indeed, what it was purported to be, and they’re the ones, most importantly, who put their money where their mouth was, ponied up the not inconsiderable cost to restore the binding, and took the time to catalog it and to bring it to the New York Book Fair, where news of its existence quickly spread as far west and south as Knoxville – as far, it turns out, as the news needed to spread. I called Steve back. “It’s here,” I said. “Is it real?,” he asked. “Yes,” I answered. “I want it,” he said. Done and done.

So, Steve is the other real hero of this story. Getting wind of a great treasure with deep and significant roots in Tennessee, the state for which his library is the rare book depository of record, he immediately did what he was hired to do: he tracked the thing down and, false leads and vague rumors notwithstanding, bagged his prey.

And so the deal was done: two days later I was in my van on my way to Knoxville, where Steve and his entire Special Collections staff were waiting for me. They even threw a party in my honor (well, actually, they were having a party anyway, and they invited me along). In a quiet room in a distant corner of the McClung Museum, I unveiled the Jackson Bible for a small party of librarians and library patrons:

Once I’d removed the Bible from its rolling case and the layers of bubble wrap in which I’d encased it for the journey (I mean, this thing was hermetically sealed and bulletproof: I’d made sure that if by some tragedy my van ran off a cliff in the Great Smoky Mountains, my van and myself might perish in flames but Jackson’s Bible would survive), everyone just stood and stared for a minute. I took a few moments to show off some of what I considered to be the Bible’s finer points – the elaborate red morocco binding, signed on the front turn-in by James Birdseye, the journeyman finisher who completed the gilt decorations, and the two pages of genealogical register, on which had been recorded General Andrew Jackson’s death, “peacefully, at home in the Hermitage, on the night of June 8, 1845″. There was a brief, slightly awed hush in the room. Then someone said: “I doubt he ever read the part about the Ten Commandments.” Someone else said: “I doubt he ever got past the Old Testament.” Someone else said, “I doubt he ever opened it at all.” At which point I knew this Bible had found its rightful home.

Serendipity, indeed.

* (now accept my apologies as you ask yourself, as I have just asked myself: can you really countenance yet another antiquarian bookseller quoting Milton? Can you? Really?).

- See more at: http://blog.lornebair.com/#sthash.EL4blYjL.dpuf