Last month I bought three pamphlets about a murder that took place in Salem, Massachusetts in 1830. It was a sensational affair in its day, a victory for prosecutor Daniel Webster, and an interesting sidelight in the history of American jurisprudence.

Last month I bought three pamphlets about a murder that took place in Salem, Massachusetts in 1830. It was a sensational affair in its day, a victory for prosecutor Daniel Webster, and an interesting sidelight in the history of American jurisprudence.

But that was not why I bought the pamphlets.

In 1829 William Low of Salem was sent to Canton to manage the affairs of Russell & Co. the great American China Trade firm. He brought his wife along and, to keep her company, his twenty-year-old niece, Harriett Low.

Happily for posterity, Harriett kept a detailed diary of her years in China. The Low household was a center of social life for American traders in Canton, and Harriett saw, and wrote about, everyone of importance in that group. Her diary was excerpted in Emma Liones's classic book China Trade Post-Bag, and reprinted in its entirety about fifteen years ago as Lights and Shadows in Macao Life.

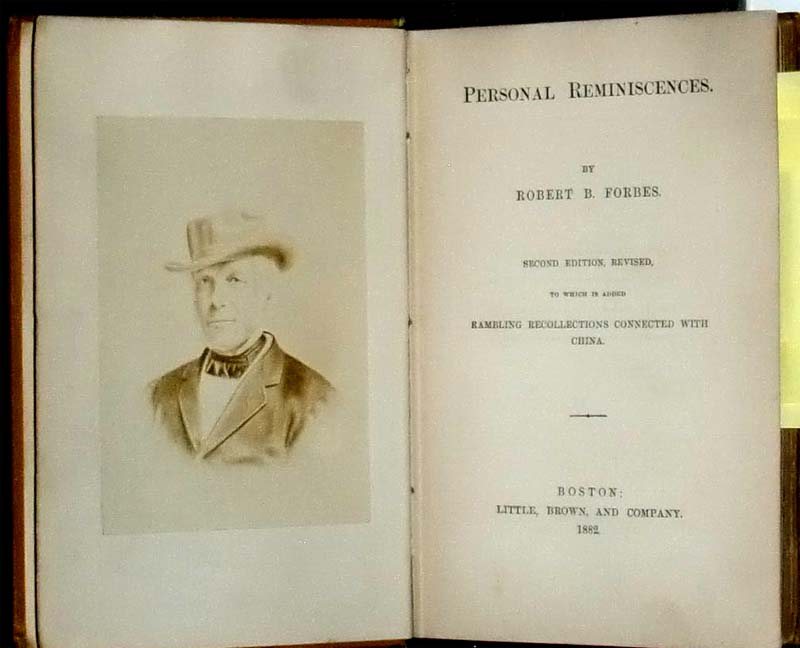

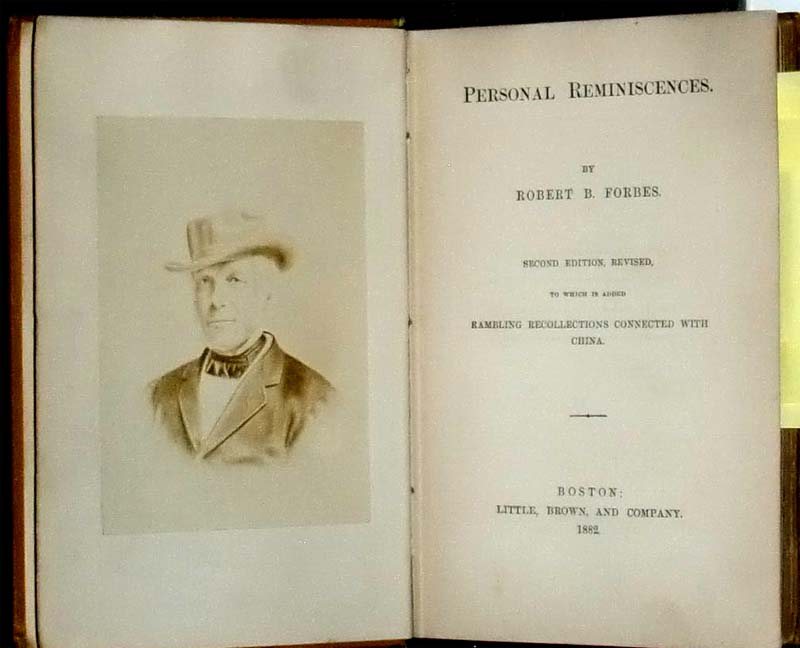

She met Robert Bennett Forbes, AKA “Black Ben,” author of one of the great American autobiographies, his brother John Murray, who would go on to become one of the great commercial minds in American history, and George Chinnery

She met Robert Bennett Forbes, AKA “Black Ben,” author of one of the great American autobiographies, his brother John Murray, who would go on to become one of the great commercial minds in American history, and George Chinnery

the eccentric and gifted painter (the old lech was sweet on Harriett and painted a lovely portrait of her. I visit it every once in a while at the Peabody Essex Museum), and Robert Morrison, the great missionary and translator, and William Hunter, a young American who went native and penned one of the liveliest accounts of China Trade life. She fell in love and suffered a broken heart. She entertained an endless stream of diplomats, missionaries, navy men, and famous American sea captains (quite a few of whom wrote about in their diaries and letters).

the eccentric and gifted painter (the old lech was sweet on Harriett and painted a lovely portrait of her. I visit it every once in a while at the Peabody Essex Museum), and Robert Morrison, the great missionary and translator, and William Hunter, a young American who went native and penned one of the liveliest accounts of China Trade life. She fell in love and suffered a broken heart. She entertained an endless stream of diplomats, missionaries, navy men, and famous American sea captains (quite a few of whom wrote about in their diaries and letters).

Harriett met everyone and recorded everything in the tumultuous and exciting years leading up to the First Opium War. But she never talked about what Russell & Co. were actually doing over there.

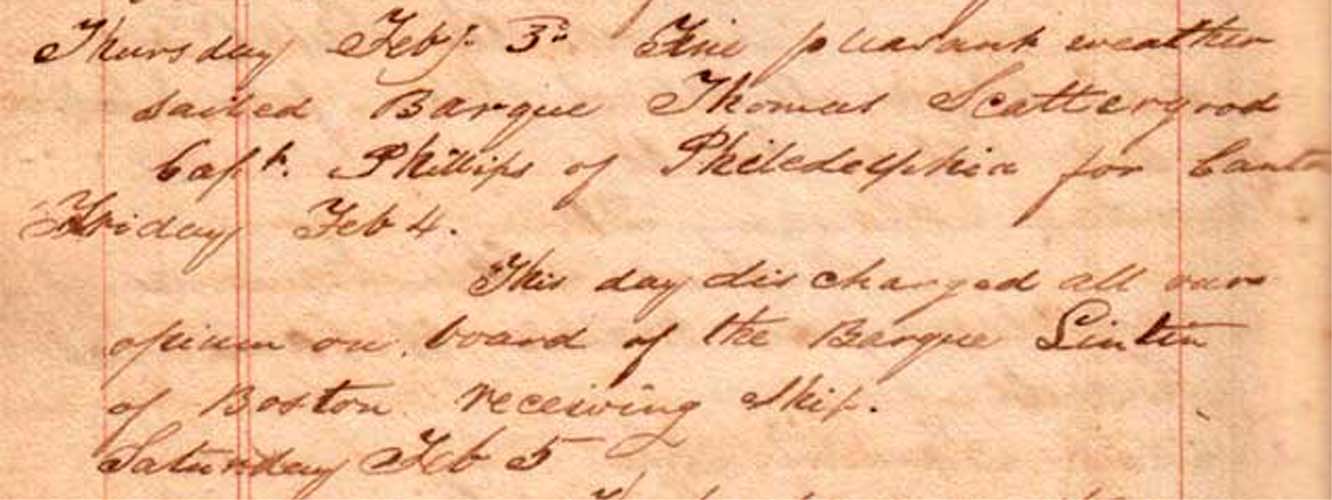

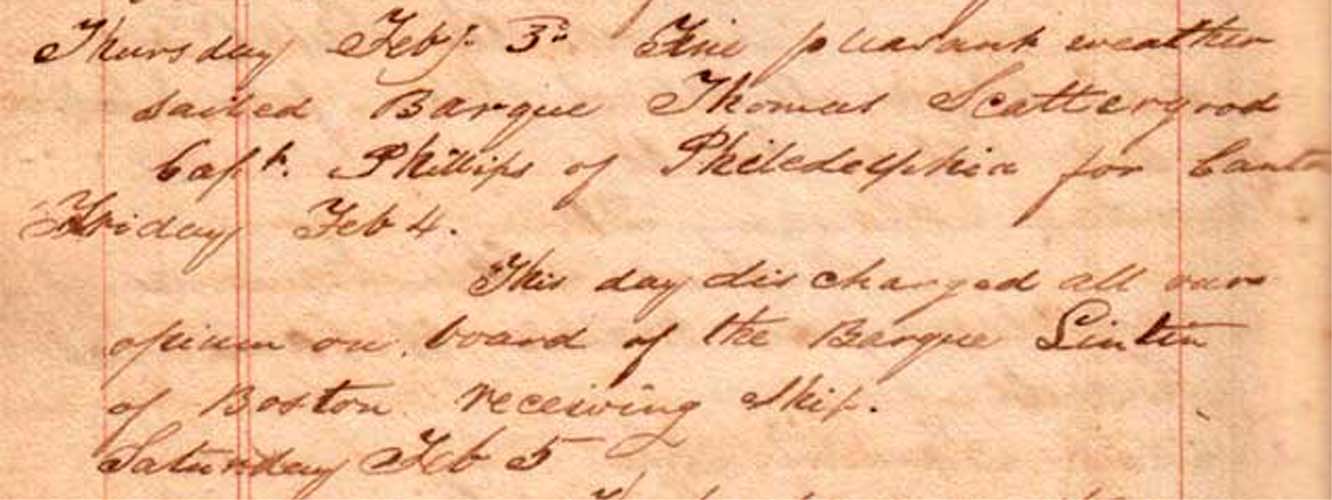

That question is answered (not that there was ever any doubt!) in the journal of the Salem trading ship Sumatra, which I will be offering for sale in my next catalog (see my blog entry for March 30, 2014). The Americans were importing opium from Turkey and offloading it to Black Ben's receiving ship on Lintin Island. The drug was used as a substitute for specie (in desperately short supply in Britain and America) to obtain Chinese goods.

But back to those pamphlets.

It turns out that the convicted murderers were the brothers of Harriett's aunt. When the news arrived in China the poor woman was devastated, forced to keep her connection to the terrible crime a secret lest her social standing be ruined.

Nothing more than historical trivia, I know. I'll probably never sell those pamphlets, and they'll go into my China Trade reference collection, already brimming with books about characters like Ledyard, Morris, Shaw, McGee, Perkins, Cushing, Russell, the Low family, the Forbes brothers, Hunter, Green, and Delano.

Maybe those are just names to you. But to me they are as real and present as people who live in my town. I know them all - the whole clan - and their quirks, and their families, and the people they knew, and I can see the places and feel the times they moved through as clearly as if I were watching a movie or reading a novel.

In fact, it is a novel – one I've been trying, and failing, to write for twenty years. It's called Opium Lives and it stars Harriet and Black Ben, with a supporting casts of those dozens of remarkable New Englanders who lived and worked in the looming shadow of the First Opium War.

I've got half a dozen outlines and at least three false starts. My problem is that the story is too big, too close. I need to get some distance on it. But how much farther away can I get from events that took place halfway around the world two centuries ago?

More often than not, when I'm out scouting books, I'll come across something like those three pamphlets, and I'm right back in Macao, having a drink in Chinnery's studio, watching him ogle Harriett, or sailing up the Pearl River with Black Ben.

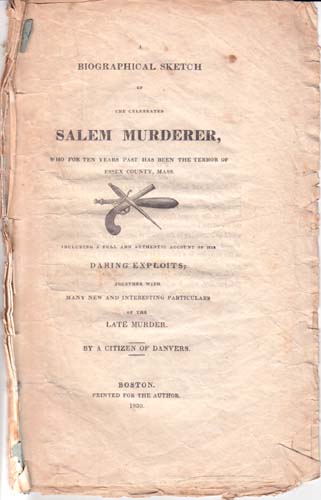

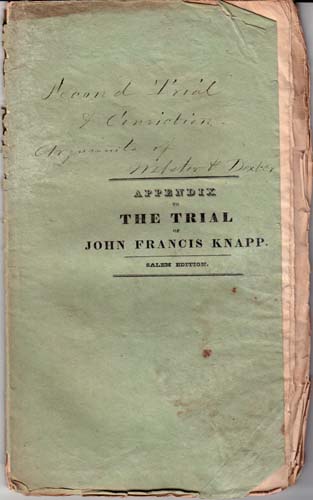

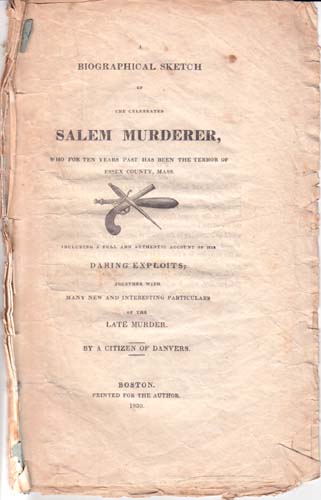

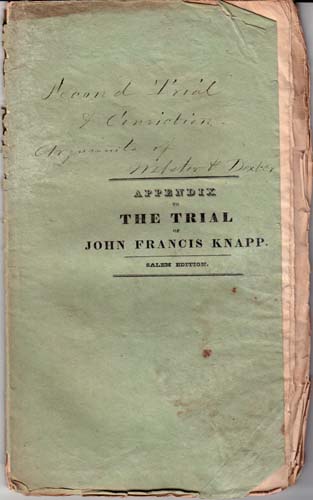

A Report of the Evidence and Points of Law, Arising in the Trial of John Francis Knapp for the Murder of Joseph White, Esquire... Salem, 1830. 74 pp. b/w plates. Half title present, but lacks wrappers. (and) Appendix to the Report of the Trial of John Francis Knapp... on the Second Trial. “Salem Edition”, 1830. 72 pp. In original printed wrappers (and) Biographical Sketch of the Celebrated Salem Murderer... Boston, 1830. 24 pp. Lacks wraps and frontispiece. John and Francis Knapp had a wealthy uncle named Joseph White, from whom they hoped to inherit a large sum. Impatient for the money, they hired a hit man who did the deed, throwing Salem into a panic. Eventually a fellow criminal ratted out the killer who promptly ratted out then Knapps and committed suicide. Daniel Webster prosecuted a tricky murder trial in which the murderer was dead and the conspirators had not been present to the crime. In a precedent setting argument Webster convinced the jury that the mere proximity of the brother was tantamount to having been present for the murder. The two were found guilty and executed. These three pamphlets are typical of the flurry of publicity generated by the murder. The lot $350

A Report of the Evidence and Points of Law, Arising in the Trial of John Francis Knapp for the Murder of Joseph White, Esquire... Salem, 1830. 74 pp. b/w plates. Half title present, but lacks wrappers. (and) Appendix to the Report of the Trial of John Francis Knapp... on the Second Trial. “Salem Edition”, 1830. 72 pp. In original printed wrappers (and) Biographical Sketch of the Celebrated Salem Murderer... Boston, 1830. 24 pp. Lacks wraps and frontispiece. John and Francis Knapp had a wealthy uncle named Joseph White, from whom they hoped to inherit a large sum. Impatient for the money, they hired a hit man who did the deed, throwing Salem into a panic. Eventually a fellow criminal ratted out the killer who promptly ratted out then Knapps and committed suicide. Daniel Webster prosecuted a tricky murder trial in which the murderer was dead and the conspirators had not been present to the crime. In a precedent setting argument Webster convinced the jury that the mere proximity of the brother was tantamount to having been present for the murder. The two were found guilty and executed. These three pamphlets are typical of the flurry of publicity generated by the murder. The lot $350

Last month I bought three pamphlets about a

Last month I bought three pamphlets about a  She met Robert Bennett Forbes, AKA “Black Ben,” author of one of the great American autobiographies, his brother John Murray, who would go on to become one of the great commercial minds in American history, and

She met Robert Bennett Forbes, AKA “Black Ben,” author of one of the great American autobiographies, his brother John Murray, who would go on to become one of the great commercial minds in American history, and  the eccentric and gifted painter (the old lech was sweet on Harriett and painted a lovely portrait of her. I visit it every once in a while at the Peabody Essex Museum), and Robert Morrison, the great missionary and translator, and William Hunter, a young American who went native and penned one of the liveliest accounts of China Trade life. She fell in love and suffered a broken heart. She entertained an endless stream of diplomats, missionaries, navy men, and famous American sea captains (quite a few of whom wrote about in their diaries and letters).

the eccentric and gifted painter (the old lech was sweet on Harriett and painted a lovely portrait of her. I visit it every once in a while at the Peabody Essex Museum), and Robert Morrison, the great missionary and translator, and William Hunter, a young American who went native and penned one of the liveliest accounts of China Trade life. She fell in love and suffered a broken heart. She entertained an endless stream of diplomats, missionaries, navy men, and famous American sea captains (quite a few of whom wrote about in their diaries and letters).

A Report of the Evidence and Points of Law, Arising in the Trial of John Francis Knapp for the Murder of Joseph White, Esquire... Salem, 1830. 74 pp. b/w plates. Half title present, but lacks wrappers. (and) Appendix to the Report of the Trial of John Francis Knapp... on the Second Trial. “Salem Edition”, 1830. 72 pp. In original printed wrappers (and) Biographical Sketch of the Celebrated Salem Murderer... Boston, 1830. 24 pp. Lacks wraps and frontispiece. John and Francis Knapp had a wealthy uncle named Joseph White, from whom they hoped to inherit a large sum. Impatient for the money, they hired a hit man who did the deed, throwing Salem into a panic. Eventually a fellow criminal ratted out the killer who promptly ratted out then Knapps and committed suicide. Daniel Webster prosecuted a tricky murder trial in which the murderer was dead and the conspirators had not been present to the crime. In a precedent setting argument Webster convinced the jury that the mere proximity of the brother was tantamount to having been present for the murder. The two were found guilty and executed. These three pamphlets are typical of the flurry of publicity generated by the murder. The lot $350

A Report of the Evidence and Points of Law, Arising in the Trial of John Francis Knapp for the Murder of Joseph White, Esquire... Salem, 1830. 74 pp. b/w plates. Half title present, but lacks wrappers. (and) Appendix to the Report of the Trial of John Francis Knapp... on the Second Trial. “Salem Edition”, 1830. 72 pp. In original printed wrappers (and) Biographical Sketch of the Celebrated Salem Murderer... Boston, 1830. 24 pp. Lacks wraps and frontispiece. John and Francis Knapp had a wealthy uncle named Joseph White, from whom they hoped to inherit a large sum. Impatient for the money, they hired a hit man who did the deed, throwing Salem into a panic. Eventually a fellow criminal ratted out the killer who promptly ratted out then Knapps and committed suicide. Daniel Webster prosecuted a tricky murder trial in which the murderer was dead and the conspirators had not been present to the crime. In a precedent setting argument Webster convinced the jury that the mere proximity of the brother was tantamount to having been present for the murder. The two were found guilty and executed. These three pamphlets are typical of the flurry of publicity generated by the murder. The lot $350