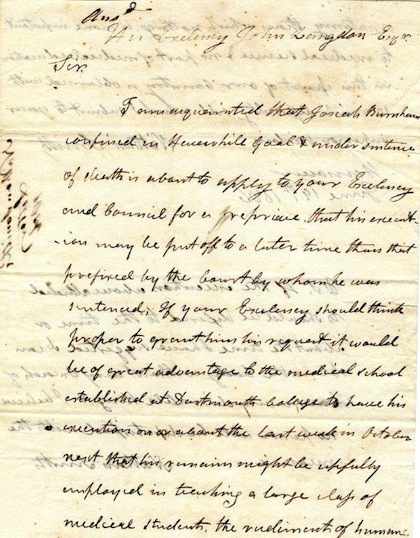

“Nothing is more important to medical science & no part of medical education in this part of the country is obtained with so much difficulty” as the study of anatomy with the use of cadavers. So wrote Dr. Nathan Smith to New Hampshire Governor John Langdon in June 1806. One of the leading medical practitioners and educators of early 19th century America, Smith founded or helped establish four schools of medicine in New England, including those at Dartmouth, Yale, Bowdoin, and the University of Vermont.

In the United States, cadavers for anatomy classes were difficult to come by – legally – until at least the 1830s. Anatomical dissection of the human body was viewed with deep suspicion, if not revulsion, especially in New England's clergy-dominated culture. In the early decades of the Republic, traffic in human remains remained largely an underground enterprise involving physicians and body snatchers (or “resurrectionists,” as they were known). Exceptions to the rule might be made, usually in the case of executed criminals whose bodies might be either sold by a creditor or released by the state – which provides the context of Smith's letter.

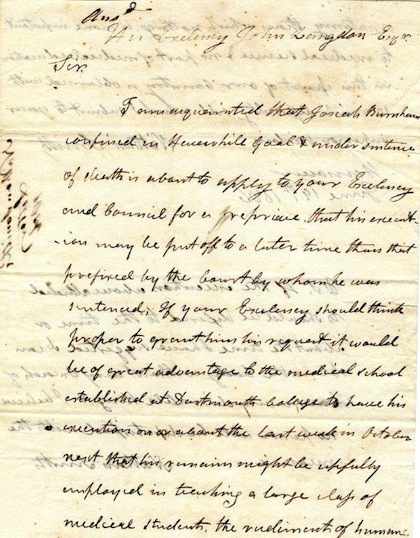

The Nathan Smith letter, page 1

Several weeks before Smith wrote to the Governor, a New Hampshire man named Josiah Burnham had been sentenced to death for the brutal murders of two others. During his sixty-plus years of life, Burnham had worked variously as a whaler, a successful surveyor, and a landowner before becoming involved in a series of serious disputes with neighbors in Haverhill, a northerly town overlooking the Connecticut River. His circumstances reduced, Burnham lost his property, fell into debt, and spent several terms in debtor's prison. In December 1805, while incarcerated for the same offense, Burnham shared his cell with Russell Freeman and Captain John Starkweather Jr. Evidently, the two men taunted Burnham about his relationship with a certain woman. Not appreciating their sarcasm, Burnham pulled out a scythe blade that – astonishingly – had not been confiscated, and proceeded first to disembowel Freeman, then stabbed Starkweather repeatedly in the chest.

“They had it coming” – or words to that effect – was as much of a defense as Burnham had to offer. His trial is notable for a number of reasons, including the fact that the junior attorney for the defense was a young, little-known lawyer from tiny Boscawen, New Hampshire named Daniel Webster. After the senior counsel all but quit the case, Webster argued for the first and only time in his long career against the constitutionality of capital punishment. To no avail.

The case itself was a media sensation: blood and guts a-plenty, a vengeful killer, and a hanging. Public executions of the day provided broad opportunity for the community. They offered both a ghoulish entertainment and enlightenment on matters of conduct and religion, as well as monetary profit. On execution day in Haverhill, more than 10,000 spectators reportedly showed up with their picnics, listened approvingly to the obligatory sermon, and thrilled as Burnham was “launched into eternity.” For the edification of the public, an eleven page confessional was printed entitled “An Analysis or Outline of the Life and Character of Josiah Burnham ... Communicated by Himself” priced at “1 dol. per doz. 12 1-2 cents per single.”

That Burnham was guilty of murder had been a foregone conclusion. He was scheduled to be hanged on July 15, 1806. However, in June Burnham wrote an appeal to Governor Langdon for a stay of execution. Apparently, even before Burnham's appeal landed on the governor's desk, Dr. Nathan Smith also wrote the governor. His letter explicitly references Burnham's upcoming appeal. Further, Dr. Smith made additional requests regarding both the timing of the execution and possession of the body afterward.

Long before Burnham's neck was stretched, Dr. Smith had eyed him as a candidate for dissection by his medical students at Dartmouth College, some 40 miles south of Haverhill. One of the most knowledgeable surgeons in America, Nathan Smith's medical accomplishments included saving the leg, if not the life, of eight year old Joseph Smith, later the founder of the Mormon church. The boy, who was not related to the physician, had a life-threatening bone infection. The usual procedure was to amputate. Dr. Smith used a surgical technique that was known only in Europe at the time to save the limb of the future Mormon prophet.

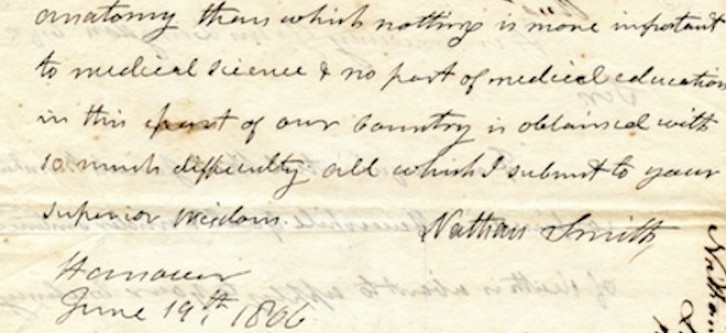

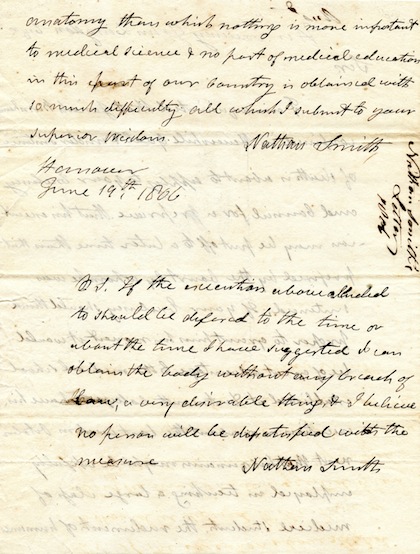

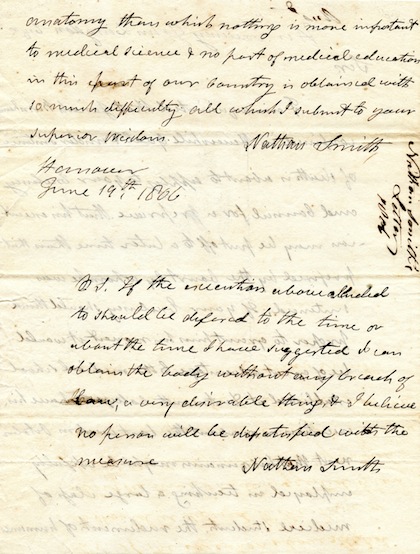

Transporting Burnham's corpse in the July heat, and then storing it for an unspecified time, presented a unique set of problems. From Dr. Smith's perspective, it would be better if the execution could be delayed a few months. Smith's letter to Governor Langdon makes clear he knew that Burnham was “about to apply to your Excellency and the Council for a reprieve that his execution be put off to a better time than that prefixed by the Court by whom he was sentenced.” Dr. Smith explicitly suggests moving the date to the “last week of October next that his remains might be usefully employed...” In a post-script Smith adds that if the execution can be delayed until October, “I can obtain the body without any breach of law, a very desirable thing & I believe no person will be dissatisfied with the measure.”

The Nathan Smith letter, page 2

The question, of course, is whether the doctor had contacted the condemned man in order to actively intervene in the judicial process for his own professional reasons. Circumstantially, that appears to have been the case. Governor Langdon did move the execution date to August 12 – but still long before the arrival of cooler autumn temperatures that Smith wanted. It's not known to this writer whether Burnham's body was immediately buried, or whether some more clinical use was made of it.

[Special thanks to Dartmouth College Archives for permitting use of the Nathan Smith letter.]