Another controversy over Shakespeare erupted recently. By itself, this fact would not be worth reporting, as controversy swirls around the legacy of William Shakespeare like that of no other writer. However, this one revolved around something that collectors of rare books will have special interest in and knowledge of: printers marks.

First, the Claim and Supporting Evidence

Cover of the May 20th edition of Country Life magazine, in which Mark Grffiths' revealed his theory.

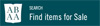

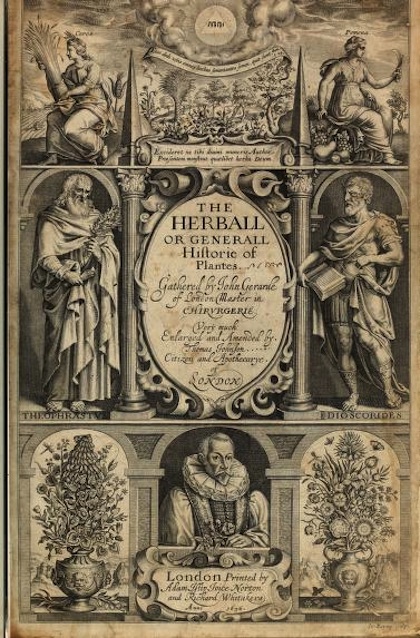

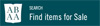

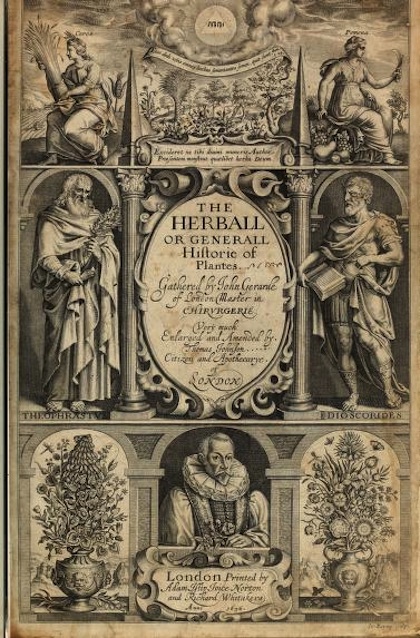

Botanist and historian Mark Griffiths was writing a book on 16th century horticulturist John Gerard, in the course of which he decided to determine who the four figures depicted on the title page of Gerard’s magnum opus, The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), were, as it is thought these figures are allegorical.

Search abaa.org for copies of John Gerard's The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes...

Search abaa.org for copies of John Gerard's The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes...

Three of the four figures appear relatively straight-forward and uncontentious: the author himself, his patron -- Lord Burghley (who raised Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford and for many the prime suspect for who could have written the Shakespeare plays if William did not), and Rembert Dodoens, the Flemish botanist whose work Gerard was building upon. The fourth figure is less obvious, and this is the one Griffiths believes to be William Shakespeare.

Title page of The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard (1597). The area around the bottom-right figure has been artificially lightened for emphasis.

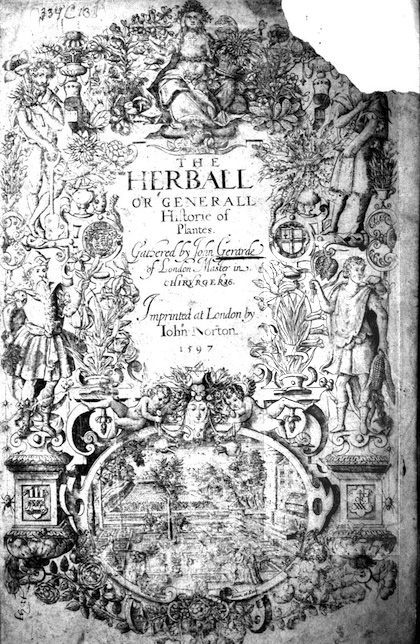

The figure at the lower right stands upon a plinth. A rebus appears (enlarged, below left) to contain a coded message, perhaps to the identity of the figure.

I’ll quote from The Guardian to explain how Griffith’s deciphers the rebus in question, and why he believes the figure represented is William Shakespeare:

“Slowly, after reading up on how devious the Elizabethans were in encoding their meanings, Griffiths began to solve the clues provided by the symbols and flowers around the fourth man.

They include:

• A figure four and an arrow head with an E stuck to it. In Elizabethan times, people would have used the Latin word “quater” as a slang term for a four in dice and cards. Put an e on the end and it becomes quatere, which is the infinitive of the Latin verb quatior, meaning shake. Look closely and the four can be seen as a spear.

• A figure four and an arrow head with an E stuck to it. In Elizabethan times, people would have used the Latin word “quater” as a slang term for a four in dice and cards. Put an e on the end and it becomes quatere, which is the infinitive of the Latin verb quatior, meaning shake. Look closely and the four can be seen as a spear.

“It is a very beautiful example of the kind of device that Elizabethans, particularly courtiers, had great fun creating,” said Griffiths.

• A W – for William? And Or? A few months before it was engraved, Shakespeare’s father was granted a coat of arms with a golden background. The heraldic term for gold is Or.

• He is holding a snake’s head fritillary (fritillaria meleagris), which had been discovered in France 20 years earlier and whose use in British gardens was pioneered by Gerard. “It was a sensational horticultural novelty, people were very excited. It was as hot as an equatorial orchid would have been to the Victorian sensibility,” said Griffiths. In Venus and Adonis, Shakespeare did not have Adonis metamorphose into an anemone after being gored by a boar, as tradition dictated. He turned him into a snake’s head fritillary.

“Believe me, there is only one piece of Elizabethan creative writing that refers to this extraordinary new flower and that is Venus and Adonis,” said Griffiths.

• Two irises, one French, one English, can be seen as referring to Henry VI Part One.

• An ear of sweetcorn the man is holding refers, Griffiths argues, to the play Titus Andronicus and the speech Marcus makes about gathering the sad-faced people of Rome, “this scatter’d corn into one mutual sheaf.”

Griffiths believes all the clues lead to it being Shakespeare and said he had not a shred of doubt. “For me, it is not about doubt or supposition. I’m faced with a series of facts that I can’t gainsay, as much as I try. This is what these facts are, these are what the plants are, this is what they signify, this is what the symbol decodes as. All of that adds up to Shakespeare. I can’t make that – and believe me I’ve tried – add up to anybody else but Shakespeare.”

So, the main thrust is that the letters appear to make the shape of a spearhead, the connection between the letters OR and Shakespeare’s father’s new coat-of-arms, and the apparent W in the last line being a nod to “William.” The exact flowers and plants are of course of great interest to a botanist -- and prehaps such clues will inevitably be of less importance to scholars in other fields? But, would most people -- even educated people -- be aware of the link between the snake’s head fritillary and Venus and Adonis, or the connection between sweetcorn and Titus Andronicus? (Personally, I'd buy the nod to Titus more easily if the figure was dismembered. Seriously, that's the most violent and gory play in the whole Shakespeare canon -- no mean feat.)

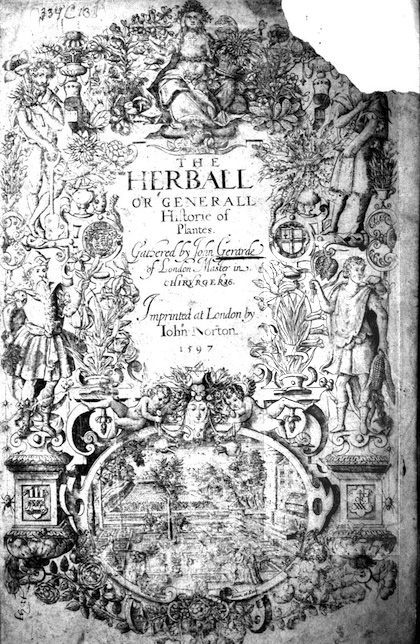

Detail from the title page.

Now, the Push Back from Shakespeare Scholars

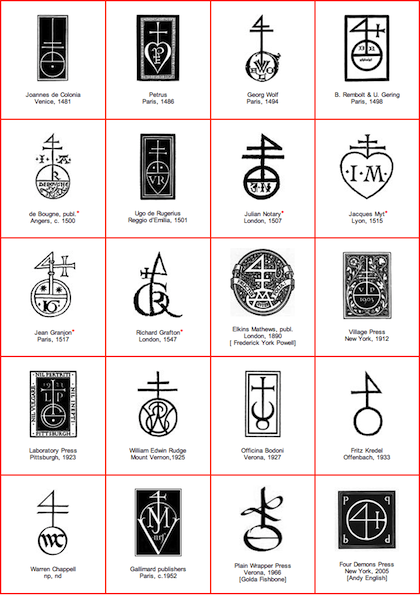

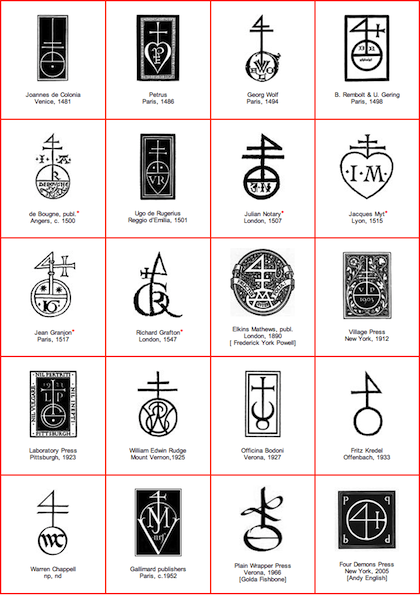

Is the theory plausible? Superficially, yes. The theory received notice in various reputable British newspapers. However, two authorities, Barry R. Clarke and John Overholt (Curator of Early Modern Books at the Houghton Library) writing separately, quickly shot down the theory, based on something rare book collectors familiar with books printed in the 1500s and 1600s will be well aware of: printers marks.

A variety of printers' marks incrporating the sign of the four.

Both interpreted the rebus as a previosuly unknown printer’s mark identifying John Norton. The Herball was printed by Norton, who appears to have trained with his uncle , the printer William Norton, and continued the firm’s work after William’s death in 1593.

Overholt identifies the “spear shape” as a form of the Chi-Rho symbol which many printers incorporated into their marks to denote their Christian faith as the “sign of the four.” The letters N, O and R being the first part of Norton, and the last line, in which Griffiths detected a W, is really three intertwined Xs, the roman numeral representing ten (Nor-ten).

Overholt then goes one step further, to answer the question of who the figure does represent if not Shakespeare:

"One excellent candidate is the Greek botanist Dioscorides; as one of the ancient founders of the field, he’s a logical choice to represent on the title page of this book."

In fact, the second edition of The Herball (1636) appears to make the identity plain, with Dioscorides being helpfully named in the lower-right position.

Title page of the 1636 edition of The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard

Case Closed?

As ever with Shakespeare scholarship, the question is likely to linger and recur with some frequency. Perhaps the fourth figure is Shakespeare, and the rebus a clever play on the printer’s mark? After all, the whole purpose of a rebus was to conceal information from the general public. Then again, perhaps not. After all, there are only three male figures on the title page of the second (1636) edition. What happened the fourth? Perhaps the next avenue of research will be why “Shakespeare” was removed from his place on the title page of The Herball?

Conspiracy theories about Shakespeare occur with such regularity and are held with such fervor that the one thing we can say with certainly is that this new claim shows that interest in the Bard remains high, and the passions of Shakespeareans are easily enflamed. At a time when the book is reputed to be at risk, it’s encouraging to be reminded that at least one writer remains capable of inspiring argument and high passion 400 years after his death.

No doubt, we’ll still be arguing about Shakespeare 400 years hence.

---

The Doves Press' Venus and Adonis (1912)

The Doves Press' Venus and Adonis (1912)

Offered by Philip J. Pirages Fine Books & Manuscripts

Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Third Folio. (1664)

Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Third Folio. (1664)

Offered by James Cummins Bookseller, Inc.

Search abaa.org for copies of John Gerard's

Search abaa.org for copies of John Gerard's

• A figure four and an arrow head with an E stuck to it. In Elizabethan times, people would have used the Latin word “quater” as a slang term for a four in dice and cards. Put an e on the end and it becomes quatere, which is the infinitive of the Latin verb quatior, meaning shake. Look closely and the four can be seen as a spear.

• A figure four and an arrow head with an E stuck to it. In Elizabethan times, people would have used the Latin word “quater” as a slang term for a four in dice and cards. Put an e on the end and it becomes quatere, which is the infinitive of the Latin verb quatior, meaning shake. Look closely and the four can be seen as a spear.

The Doves Press' Venus and Adonis

The Doves Press' Venus and Adonis