“The greatest beauty is organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe.” -- from “The Answer” by Robinson Jeffers

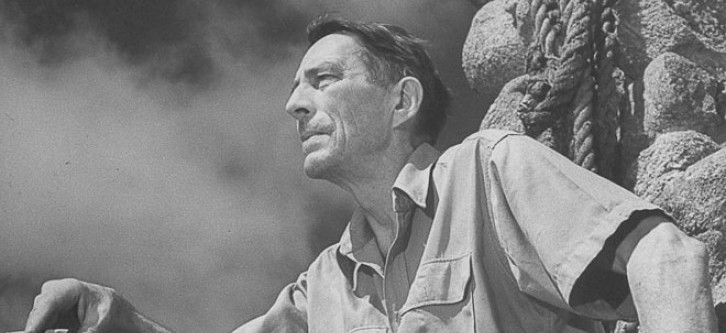

Within his lifetime, the work of Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962) was at various points revered, deliberately shunned, and generally neglected.

In 1932, the poet was featured on the cover of Time magazine; but by 1948 his publisher, Random House, saw fit to add a “Publisher’s Note” to his collection The Double Axe in which they expressed their “disagreement over some of the political views pronounced by the poet in the volume.” By the time of his death he had already passed into irrelevance, with younger poets such as Kenneth Rexroth attacking him and his work rarely anthologized. Still, his work was read and studied by other poets such as Gary Snyder (who noted his work showed “a profound respect for the non-human”) and his greatest disciple William Everson, and today, despite his continuing marginalization in some circles as a “California poet,” his work continues to reckoned with.

Critic and Poet Laureate of California Dana Gioia, a great modern-day champion of Jeffers, has noted, “I consider Jeffers the most important American poet in the western third of the country—the great poet of the West.” Gioia adds, “He’s a titanic if singular figure,” and therein lies some of the difficulty in dealing with Jeffers.

Jeffers’ theory of “inhumanism,” which the poet described as being “based on a recognition of the astonishing beauty of things and their living wholeness, and on a rational acceptance of the fact that mankind is neither central nor important in the universe; our vices and blazing crimes are as insignificant as our happiness,” has long endeared him to environmentalists. But its flinty, bleak vision can be a bitter pill; and his verse dramas, full of violence and gothic horror, still retain the power to shock.

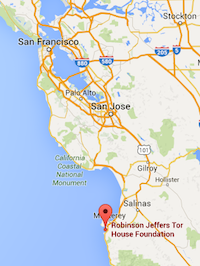

Although the description of Jeffers as a California poet can be isolating, it is a true statement, and his distinct voice developed directly through his relationship with nature and specifically the rocky, wave-battered coast of Carmel and Point Lobos, just north of Big Sur on the California coast.

Although the description of Jeffers as a California poet can be isolating, it is a true statement, and his distinct voice developed directly through his relationship with nature and specifically the rocky, wave-battered coast of Carmel and Point Lobos, just north of Big Sur on the California coast.

In “The Waste Land,” published in 1922, T.S. Eliot described the collapse of modern civilization through use of ancient myths, of the “unreal” cities, “the dry stone no sound of water,” “no water but only rock / Rock and no water and the sandy road.” Jeffers’ voice, just as modern, but shut off from the eastern and European schools, was hewn directly from the stone of Carmel, those stones building the tower he erected with his own hands:

It has all time. It knows the people are a tide

That swells and in time will ebb, and all

Their works dissolve. Meanwhile the image of the pristine beauty

Lives in the very grain of the granite,

Safe as the endless ocean that climbs our cliff. – As for us:

We must uncenter our minds from ourselves;

We must unhumanize our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we were made from.

--from “Carmel Point” by Robinson Jeffers

Jeffers came to Carmel in the fall of 1914, at the age of twenty-seven. Born in Allegheny City, now part of Pittsburgh, PA, he attended schools primarily in Europe and was tutored by his father, a Presbyterian minister and Biblical scholar. Fluent in German, French, Latin, and Greek by the age of twelve, Jeffers read deeply in the classics, philosophy, and science. An encounter with the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti as a teenager, given to him by his father, galvanized the young reader (“no lines of print will ever intoxicate as Rossetti’s rather florid verses did”).

In 1903, upon his retirement, Jeffers’ father moved his family to Los Angeles, feeling the climate would benefit his health. Jeffers attended Occidental College, then located in Highland Park, from which he graduated in 1905. Jeffers enrolled at the University of Southern California as a graduate student, first taking courses in foreign languages and then, after a semester at the University of Zurich, he came back to USC and enrolled in the medical school. After several years he lost interest in medicine, and in 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, where he remained for less than a year before returning to Los Angeles.

It was at USC, originally in 1906, that he met Una Call Kuster, three years older than him and married to a successful lawyer. Within several years they had embarked on a clandestine affair, and -- despite both their efforts to cool the relationship, he by going to Seattle, she by going to Europe for a year following his return in 1911 -- she was divorced from her husband. The scandal reached the pages of the Los Angeles Times, and in August 1913 Jeffers married Una.

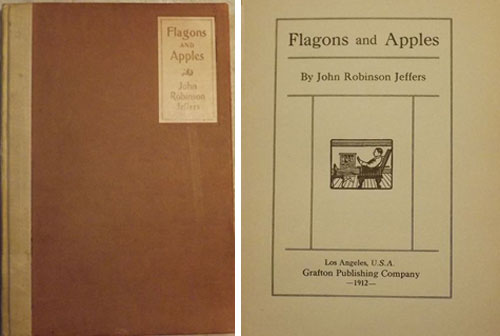

Flagons and Apples by Robinson Jeffers

1912. Los Angeles, Grafton Publishing Company. Small 8vo., tan cloth spine & brown boards; 46 pages. First Edition. Limited Edition of 500 copies. Jeffers first book, published at his own expense. (Offered by Antic Hay Books)

The newlyweds intended to move to the Dorset coast of England, but the Great War halted those plans, and seeking a quiet place to live and work, they came to Carmel. Jeffers had always written poetry, publishing work in the Occidental College magazine, and in 1912, he had published his first collection of verse, Flagons and Apples. It was printed at his own expense in an edition of 500 copies; Jeffers took twenty copies and the printer later wholesaled the remainder. Jeffers later expressed disdain for this youthful collection of love lyrics; in a 1955 inscription of the book to a Carmel neighbor he conveyed “shame-faced apologies for this.”

His next book, and first to be published by a major publisher, was Californians (1916). It was still very much apprentice work, and received very little notice. But, over the next eight years there was a major shift in his perception and work. The singular slaughter of the war marked Jeffers’ sense of a civilization in decline (although he had tried to enlist, over Una’s objections, he was by then too old).

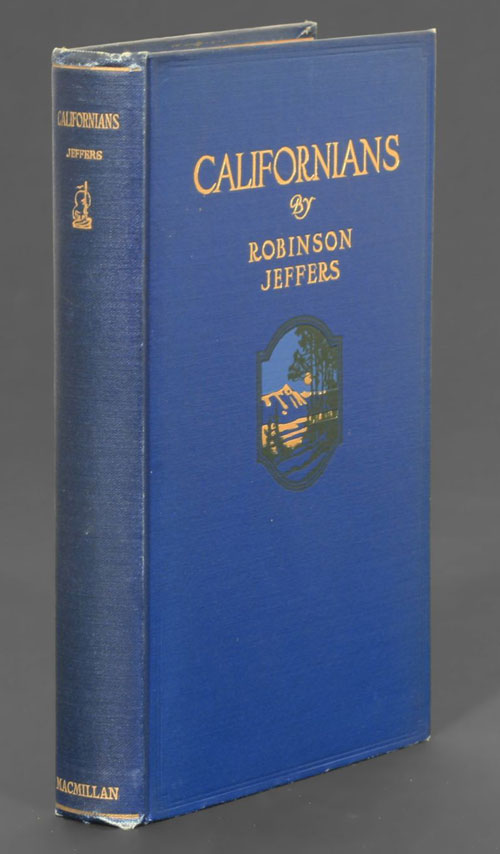

Californians by Robinson Jeffers

New York: The Macmillan Company. 1st Edition. Hardcover. Very Good. FIRST EDITION of Jeffers's second book, the first to be published by a major publishing house. (Offered by Manhattan Rare Book Company)

In 1916, Una had given birth to twin sons, and by 1919 the family purchased a plot of land just fifty yards from the water’s edge south of Carmel Village and began to build a stone house, named Tor House after the rocky outcroppings they had seen in England. Jeffers assisted as a stonemason, carrying the granite and mixing cement, and it was in this process, according to Una, that “he realized some kinship” with the stone and “there came to him a kind of awakening such as adolescents and religious converts are said to experience.”

Over the next five years he built, alone, a four-story stone tower next to the house, rolling the boulders up from the beach and raising and aligning them into place. His poetry became more stripped down, without reference to modern urban life, and completely unified with the wild, stark, beautiful, and sometimes violent landscape.

In 1924, Jeffers had printed, again at his own expense, five hundred copies of Tamar and Other Poems, the title poem a long narrative of incest and violence. The book also included several poems that have become classics, “To the Stone-Cutters” and “Continent’s End” among them.

Again the book received no notice. But the next year Jeffers was asked by his friend George Sterling to submit work for an anthology of poems by California writers, to be published by the Book Club of California. One of them, “Continent’s End,” became the title poem of the collection. Jeffers sent copies of his self-published book, then languishing in a box in his attic, to the editors of the book in appreciation, and one of those editors, James Rorty, overwhelmed by the work, wrote a review published in the New York Herald Tribune in March 1925 in which he called Jeffers a “poet of genius.” Other reviewers were quick to join the chorus, and once Jeffers sent the crate of books back to New York, they rapidly sold out and a new edition of the work, with additional material, was published by Boni & Liveright.

He had become, almost overnight, a famous writer. The next ten years saw Jeffers at the height of his popularity, and steady publications of his work in magazines and journals, and in book form, first published by Boni & Liveright and then by Random House, sold well. Most of his trade publications at the time were also accompanied by signed limited editions of the same book.

Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press brought his work out in England. In addition, in 1928, the Book Club of California published a fine press edition of a selection of Jeffers’ poems with a frontispiece portrait of the poet by a young photographer named Ansel Adams. This book has become one of the more collectible publications not only of Jeffers but of California literature and printing in general. Jeffers also had work printed by the Grabhorn Press, the Quercus Press (run by Theodore Lilienthal), and Ward Ritchie, a fellow Occidental alum.

By the 1940s, past fifty, Jeffers found himself writing less, and much of the earlier public acclaim for his work had faded. A second worldwide conflagration had distilled his bitter and isolationist feelings further; in the midst of such carnage what was the point of one man’s life, or one nation’s, or indeed the human race?

That public men publish falsehoods

Is nothing new. That America must accept

Like the historical republics corruption and empire

Has been known for years.

Be angry at the sun for setting

If these things anger you. Watch the wheel slope and turn

They are all bound on the wheel, these people, those warriors,

This republic, Europe, Asia.

Observe them gesticulating,

Observe them going down. The gang serves lies, the passionate

Man plays his part; the cold passion for truth

Hunts in no pack.

--from “Be Angry at the Sun” by Robinson Jeffers

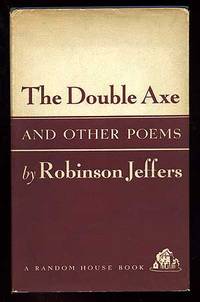

In 1947, Jeffers’ last popular triumph, an adaptation of Euripides’ Medea, starring Dame Judith Anderson and John Gielgud, opened on Broadway and ran for several hundred performances. It was followed in 1948 by The Double Axe, a collection in which his work was viewed as anti-American; it was indeed against humanity and civilization as a whole, and his outrage had curdled into misanthropy.

In 1947, Jeffers’ last popular triumph, an adaptation of Euripides’ Medea, starring Dame Judith Anderson and John Gielgud, opened on Broadway and ran for several hundred performances. It was followed in 1948 by The Double Axe, a collection in which his work was viewed as anti-American; it was indeed against humanity and civilization as a whole, and his outrage had curdled into misanthropy.

His last years were a slow decline. Una died in 1950, and although Jeffers continued to write, his life had become colorless and emptier without her. His sons moved back to Carmel and spent time with him, as his health slowly declined. He published one more book, Hungerfield and Other Poems, in 1954, the title poem a long memorial for Una. He knew that his work was not read as it had been, but as he wrote in his essay “Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years”:

“I have no sympathy with the notion that the world owes a duty to poetry, or any other art. Poetry is not a civilizer, rather the reverse, for great poetry appeals to the most primitive instincts. It is not necessarily a moralizer; it does not necessarily improve one’s character; it does not even teach good manners. It is a beautiful work of nature, like an eagle or a high sunrise. You owe it no duty. If you like it, listen to it; if not, let it alone.”

.jpg)

Hungerfield and Other Poems by Robinson Jeffers

New York: Random House. (1954). First edition. Small, attractive bookplate on the front pastedown under the front flap else fine in fine dustwrapper with one short tear. An attractive copy. (Offered by Between the Covers Rare Books)

In January 1962, after years of ill health, Jeffers died in the small room downstairs at Tor House, Carmel coated in an unprecedented layer of snow.

Snow on the headland,

Rare on the coast of California.

Snow on Point Lobos,

Falling all night,

Filling the creeks and the back country,

The strangely beautiful

Setting of death.

For the poet is dead.

The pen, splintered on the sheer

Excesses of vision, unfingered, falls.

The heart-crookt hand, cold as stone,

Lets it go down.

--from “The Poet is Dead” by William Everson

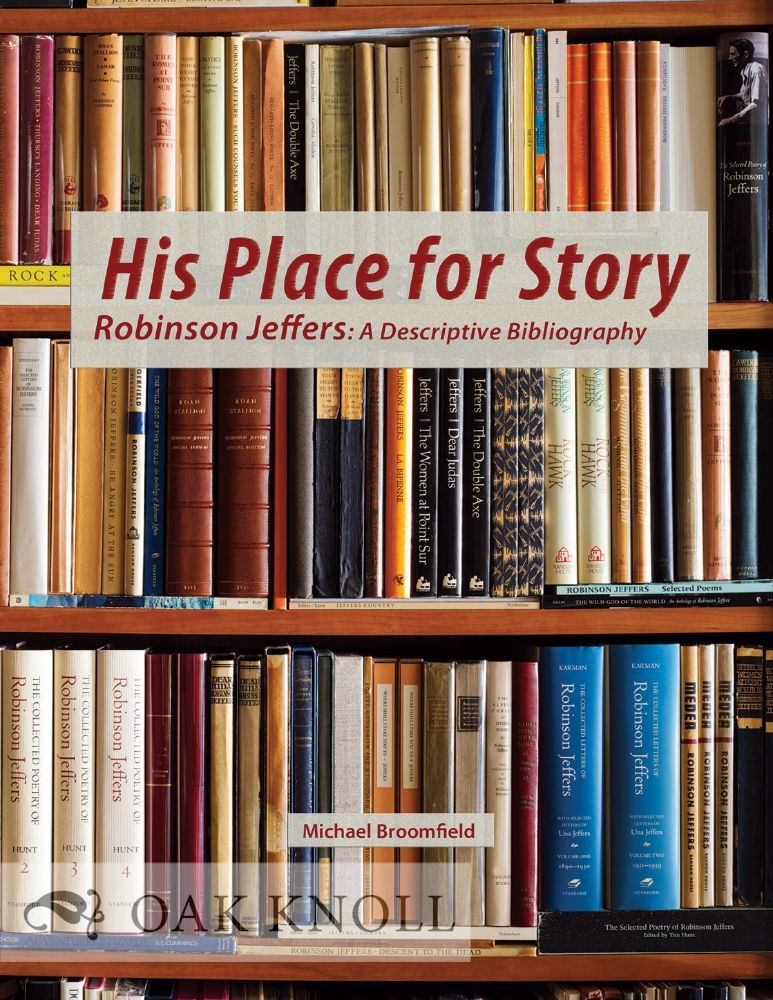

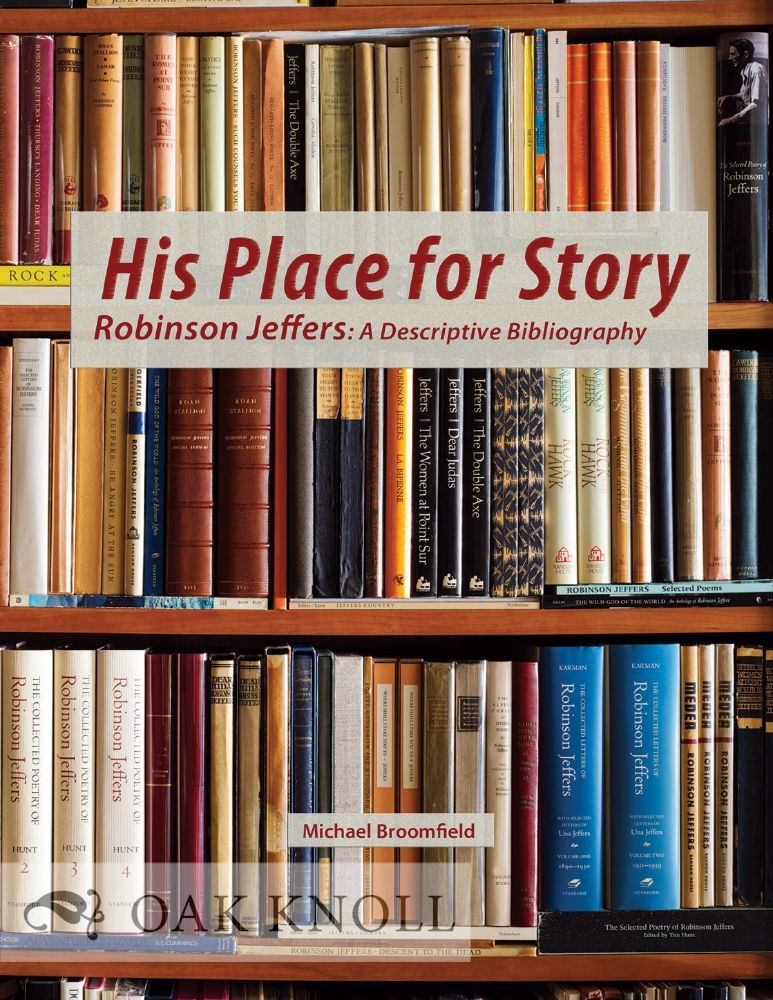

In recent years there have been several excellent critical publications — Stanford University Press’s five-volume Collected Poems, edited by Tim Hunt, and three-volume Collected Letters, edited by James Karman, along with Michael Broomfield’s much-needed descriptive bibliography, published by Oak Knoll.

In 2012, Dana Gioia organized a conference at the University of Southern California celebrating his work. Tor House and Hawk Tower, now run by a foundation, still draw visitors, even as they are now “edged in on all sides by trilevel pasteboard phantasms,” as James Tate wrote. And readers still come to the wild, strange work of this stonemason, hewing rocks and words into solid form.

---

About Robinson Jeffers:

His Place for Story: Robinson Jeffers: A Descriptive Bibliography by Michael Broomfield

New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2015. Hardcover, dust jacket. 8.5 x 11 inches. Hardcover, dust jacket. 272 pp text plus 72 pp b/w images (repeated in color on CD). "A marvelously comprehensive bibliography of Jeffers that reads like a detective novel and makes me want to peek into every item mentioned and immerse myself in his poetry." -- Charles Simic

Although the description of Jeffers as a California poet can be isolating, it is a true statement, and his distinct voice developed directly through his relationship with nature and specifically the rocky, wave-battered coast of Carmel and Point Lobos, just north of Big Sur on the California coast.

Although the description of Jeffers as a California poet can be isolating, it is a true statement, and his distinct voice developed directly through his relationship with nature and specifically the rocky, wave-battered coast of Carmel and Point Lobos, just north of Big Sur on the California coast.

.jpg)