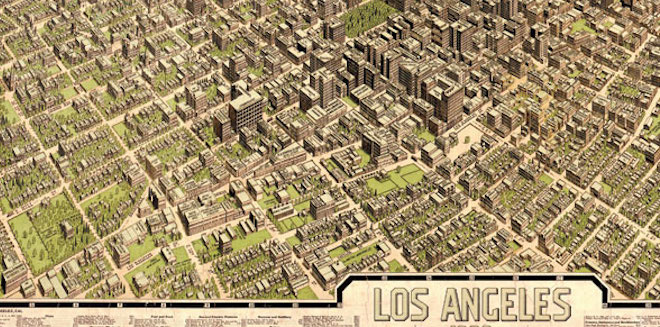

Literary Los Angeles: A Legacy as Diverse as the City Itself

The Hollywood sign looms large over Los Angeles. However, despite its close association with the motion picture industry, the enduring promise and dark undercurrents of America's first postmodern city are best understood through its prose and poetry.

This literary legacy will be on display in February when the world's leading antiquarian booksellers gather in Los Angeles for the 43rd ILAB Congress, which will lead into the 51st California International Antiquarian Book Fair in Pasadena. The following list of 20 defining works of Los Angeles literature is presented in anticipation of these prestigious events:

Reminiscences of a Ranger: Early Times in Southern California (1881) by Major Horace Bell

Horace Bell (1830-1918) was an incendiary attorney who was fond of the seamier side of life. This true account of his service with the Los Angeles Rangers, a sort of border police, rivals any dime-store western. The first book printed and bound in Los Angeles, it is particularly scarce because the type from the first half of the book was reportedly cannibalized for use in the second.

Horace Bell (1830-1918) was an incendiary attorney who was fond of the seamier side of life. This true account of his service with the Los Angeles Rangers, a sort of border police, rivals any dime-store western. The first book printed and bound in Los Angeles, it is particularly scarce because the type from the first half of the book was reportedly cannibalized for use in the second.

Ramona (1884) by Helen Hunt Jackson

Despite its romantic excess, Ramona is perhaps the most significant Southern California novel. In much the same way that Uncle Tom's Cabin helped to arouse public sentiment against slavery, the abuse of California Indians depicted in Ramona brought about reforms in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. At the same time, the landmarks associated with Jackson's eponymous heroine, a half-Indian beauty raised on a wealthy Mexican rancho, helped to make the region a tourist destination.

Despite its romantic excess, Ramona is perhaps the most significant Southern California novel. In much the same way that Uncle Tom's Cabin helped to arouse public sentiment against slavery, the abuse of California Indians depicted in Ramona brought about reforms in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. At the same time, the landmarks associated with Jackson's eponymous heroine, a half-Indian beauty raised on a wealthy Mexican rancho, helped to make the region a tourist destination.

Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913 (1916) by Harris Newmark

This work is indispensable to the student of California history for no other work contains so much detailed history concerning Southern California. It is a gold mine of historical and biographical information regarding the Los Angeles district from 1853 up to the year of Harris Newmark's death. Newmark (1834-1916) was a pioneer of 1853 and an outstanding merchant and community business leader for over half a century.

This work is indispensable to the student of California history for no other work contains so much detailed history concerning Southern California. It is a gold mine of historical and biographical information regarding the Los Angeles district from 1853 up to the year of Harris Newmark's death. Newmark (1834-1916) was a pioneer of 1853 and an outstanding merchant and community business leader for over half a century.

Ask the Dust (1939) by John Fante

.jpg) Long before Charles Bukowski became its most famous expositor, Fante captured the grim reality of poverty in Los Angeles in this poignant, Depression-era portrait of a destitute young writer who falls for an unstable Mexican waitress: "One night I was sitting on the bed in my hotel room on Bunker Hill, down in the very middle of Los Angeles. It was an important night in my life, because I had to make a decision about the hotel. Either I paid up or I got out. That was what the note said, the note the landlady had put under my door. A great problem, deserving acute attention. I solved it by turning out the lights and going to bed."

Long before Charles Bukowski became its most famous expositor, Fante captured the grim reality of poverty in Los Angeles in this poignant, Depression-era portrait of a destitute young writer who falls for an unstable Mexican waitress: "One night I was sitting on the bed in my hotel room on Bunker Hill, down in the very middle of Los Angeles. It was an important night in my life, because I had to make a decision about the hotel. Either I paid up or I got out. That was what the note said, the note the landlady had put under my door. A great problem, deserving acute attention. I solved it by turning out the lights and going to bed."

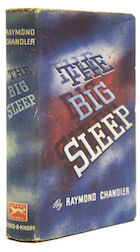

The Big Sleep (1939) by Raymond Chandler

The first of the Philip Marlowe novels, an important milestone in the evolution of the mythos of Los Angeles, as well as the detective genre: "It was about eleven o'clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark little clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn't care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars."

The first of the Philip Marlowe novels, an important milestone in the evolution of the mythos of Los Angeles, as well as the detective genre: "It was about eleven o'clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark little clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn't care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars."

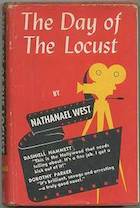

The Day of the Locust (1939) by Nathanael West

Prefiguring the nonfiction writing of Mike Davis and Norman Klein, West renders with hallucinatory precision the reverse side of the Hollywood dream, as he choreographs a cast of failures, has-beens, and deluded glamour-seekers in what becomes an apocalyptic dance of death: "Only those who still have hope can benefit from tears."

Prefiguring the nonfiction writing of Mike Davis and Norman Klein, West renders with hallucinatory precision the reverse side of the Hollywood dream, as he choreographs a cast of failures, has-beens, and deluded glamour-seekers in what becomes an apocalyptic dance of death: "Only those who still have hope can benefit from tears."

If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945) by Chester Himes

This devastating story of the broken promise of racial equality in mid-century Los Angeles is told through the eyes of Bob Jones, the only African American foreman working in a naval shipyard during World War II. Like his protagonist, Himes, whose grandfather had been a slave, moved to L.A. from Cleveland only to find racism in this city stuck to him like a “disease I couldn’t shake.”

This devastating story of the broken promise of racial equality in mid-century Los Angeles is told through the eyes of Bob Jones, the only African American foreman working in a naval shipyard during World War II. Like his protagonist, Himes, whose grandfather had been a slave, moved to L.A. from Cleveland only to find racism in this city stuck to him like a “disease I couldn’t shake.”

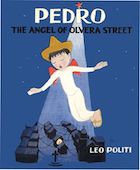

Pedro, the Angel of Olvera Street (1946) by Leo Politi

Set on Olvera Street, the site of Los Angeles' original Latino settlement, this Caldecott Honor book tells of the community's Christmas tradition of the "posada," a procession that reenacts Mary and Joseph's pilgrimage to Bethlehem. Politi (1908-96) was an Italian-American artist who, in two dozen children's books and countless drawings and paintings, celebrated the city's ethnic diversity long before "multicultural" entered the vocabulary.

Set on Olvera Street, the site of Los Angeles' original Latino settlement, this Caldecott Honor book tells of the community's Christmas tradition of the "posada," a procession that reenacts Mary and Joseph's pilgrimage to Bethlehem. Politi (1908-96) was an Italian-American artist who, in two dozen children's books and countless drawings and paintings, celebrated the city's ethnic diversity long before "multicultural" entered the vocabulary.

The Loved One (1948) by Evelyn Waugh

.jpg) The mortuary industry in Los Angeles serves as an apt metaphor for the movie business in this fiendish satire of Anglo-American culture. Much to Waugh's dismay, the novel was well received in the United States, though he claimed that American morticians would refuse to service his body should he die in the country.

The mortuary industry in Los Angeles serves as an apt metaphor for the movie business in this fiendish satire of Anglo-American culture. Much to Waugh's dismay, the novel was well received in the United States, though he claimed that American morticians would refuse to service his body should he die in the country.

Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury

.jpg) A cautionary tale set in the not too distant future when firemen burn books forbidden by the totalitarian regime. Written in the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library on a typewriter that Bradbury rented for ten cents per half hour, Fahrenheit 451 predicted with considerable foresight the distortions to come from immersive electronic media and reality television.

A cautionary tale set in the not too distant future when firemen burn books forbidden by the totalitarian regime. Written in the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library on a typewriter that Bradbury rented for ten cents per half hour, Fahrenheit 451 predicted with considerable foresight the distortions to come from immersive electronic media and reality television.

A Single Man (1964) by Christopher Isherwood

.jpg) Described by Edmund White as "the first and best novel of the gay liberation movement," A Single Man follows a day in the life of a British professor in mid-century Los Angeles, coping with the death of his longtime partner and yearning for the sense of belonging his neighbors and students seem to enjoy.

Described by Edmund White as "the first and best novel of the gay liberation movement," A Single Man follows a day in the life of a British professor in mid-century Los Angeles, coping with the death of his longtime partner and yearning for the sense of belonging his neighbors and students seem to enjoy.

Play it as it Lays (1970) by Joan Didion

.jpg) This ruthless dissection of American life in the late 1960s follows disenchanted actress Maria Wyeth as she grapples with the bleak realities of life in Hollywood. Within the subgenre of the Hollywood novel, it is one of the very few that focuses exclusively on the effects of the film industry on women.

This ruthless dissection of American life in the late 1960s follows disenchanted actress Maria Wyeth as she grapples with the bleak realities of life in Hollywood. Within the subgenre of the Hollywood novel, it is one of the very few that focuses exclusively on the effects of the film industry on women.

Kindred (1979) by Octavia E. Butler

.jpg) In this original, thought-provoking novel, a young African woman finds herself transported from her Los Angeles home to a pre-Civil War Maryland plantation. Kindred underscores the resilience of people forced to live in bondage, while also examining the dynamics of antebellum slavery and its legacy in present American society. The first science fiction novelist to receive a MacArthur Fellowship, Butler (1947-2006) is regarded as seminal figure in the Afrofuturist movement.

In this original, thought-provoking novel, a young African woman finds herself transported from her Los Angeles home to a pre-Civil War Maryland plantation. Kindred underscores the resilience of people forced to live in bondage, while also examining the dynamics of antebellum slavery and its legacy in present American society. The first science fiction novelist to receive a MacArthur Fellowship, Butler (1947-2006) is regarded as seminal figure in the Afrofuturist movement.

Less Than Zero (1985) by Bret Easton Ellis

.jpg) The theme of excess is a well-worn Los Angeles trope, but it’s never been explored more ominously than in this tour de force of 1980s materialism. Titled after the Elvis Costello song of the same name, the novel follows a rich, young college student who returns home to Los Angeles during winter break and embarks upon an odyssey of indulgence with his drug-addled and disillusioned peers.

The theme of excess is a well-worn Los Angeles trope, but it’s never been explored more ominously than in this tour de force of 1980s materialism. Titled after the Elvis Costello song of the same name, the novel follows a rich, young college student who returns home to Los Angeles during winter break and embarks upon an odyssey of indulgence with his drug-addled and disillusioned peers.

City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990) by Mike Davis

.jpg) A Marxist historical, economic, and cultural dissection of Los Angeles, its residents and their lifestyles and their interactions with real estate developers. Notable for predicting some of the tensions that would lead into the 1992 Los Angeles riots, it stills wields considerable influence in the fields of sociology and urban studies.

A Marxist historical, economic, and cultural dissection of Los Angeles, its residents and their lifestyles and their interactions with real estate developers. Notable for predicting some of the tensions that would lead into the 1992 Los Angeles riots, it stills wields considerable influence in the fields of sociology and urban studies.

Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A. (1993) by Luis J. Rodriguez

A veteran of East Los Angeles gang warfare, Rodriguez decided to document his youth in an effort to steer his teenaged son away from the same path of violence and desperation. The result was this transcendent memoir, filled with searing accounts of shootings, Mexican funerals, rapes, and arrests.

A veteran of East Los Angeles gang warfare, Rodriguez decided to document his youth in an effort to steer his teenaged son away from the same path of violence and desperation. The result was this transcendent memoir, filled with searing accounts of shootings, Mexican funerals, rapes, and arrests.

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family (1995) by Lisa See

Encompassing racism, romance, secret marriages, entrepreneurial genius, and much more, this sprawling memoir explores four generations of a Chinese American family who originally immigrated to California in 1867 and whose members have lived and worked in Los Angeles from 1897 to the present. See weaves her family legacy into the broader history of Los Angeles Chinatown, and examines the daunting challenges Chinese immigrants faced in coming to America.

Encompassing racism, romance, secret marriages, entrepreneurial genius, and much more, this sprawling memoir explores four generations of a Chinese American family who originally immigrated to California in 1867 and whose members have lived and worked in Los Angeles from 1897 to the present. See weaves her family legacy into the broader history of Los Angeles Chinatown, and examines the daunting challenges Chinese immigrants faced in coming to America.

The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory (1997) by Norman M. Klein

Melding fact and fiction, this ambitious "anti-tour" of Downtown L.A. explores how urban growth and gentrification have influenced the continual recreation of the city's own myth. In particular, Klein investigates the lives of Vietnamese immigrants and looks at the way information technology has recreated the City of Angels.

Melding fact and fiction, this ambitious "anti-tour" of Downtown L.A. explores how urban growth and gentrification have influenced the continual recreation of the city's own myth. In particular, Klein investigates the lives of Vietnamese immigrants and looks at the way information technology has recreated the City of Angels.

Bathwater Wine (1998) by Wanda Coleman

Long regarded as L.A.’s unofficial poet laureate, Coleman (1946-2013) illuminated the ironies and despair in a poor black woman’s daily struggle for dignity, while also writing tenderly and with humor about identity, tangled love, Southern California winters, and her working-class parents. This collection earned Coleman the Lenore Marshall National Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets.

Long regarded as L.A.’s unofficial poet laureate, Coleman (1946-2013) illuminated the ironies and despair in a poor black woman’s daily struggle for dignity, while also writing tenderly and with humor about identity, tangled love, Southern California winters, and her working-class parents. This collection earned Coleman the Lenore Marshall National Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets.

Embattled Dreams: California in War and Peace, 1940-1950 (2002) by Kevin Starr

The sixth volume in Starr's monumental cultural history of California examines the decade that transformed the largely agricultural state into a national power in politics, defense, manufacturing, and entertainment. Breathtaking in scope, Embattled Dreams covers such disparate subjects as San Francisco restaurants, the roots of anti-Japanese sentiment, Raymond Chandler's fiction, changes in domestic architecture, and the rise of Richard Nixon.

The sixth volume in Starr's monumental cultural history of California examines the decade that transformed the largely agricultural state into a national power in politics, defense, manufacturing, and entertainment. Breathtaking in scope, Embattled Dreams covers such disparate subjects as San Francisco restaurants, the roots of anti-Japanese sentiment, Raymond Chandler's fiction, changes in domestic architecture, and the rise of Richard Nixon.

…and if you’re hungry for more:

Counter Intelligence: Where to Eat in the Real Los Angeles (2000) by Jonathan Gold

Jonathan Gold is as much a culinary anthropologist and cultural philosopher as he is a food critic. In this collection, he explores the hidden kitchens where Los Angeles' diverse ethnic communities feed their own. In 2007, Gold received the Pulitzer Prize for criticism, a first for a food writer, and a first for his home paper, the free, alternative L.A. Weekly.

Jonathan Gold is as much a culinary anthropologist and cultural philosopher as he is a food critic. In this collection, he explores the hidden kitchens where Los Angeles' diverse ethnic communities feed their own. In 2007, Gold received the Pulitzer Prize for criticism, a first for a food writer, and a first for his home paper, the free, alternative L.A. Weekly.

*Special thanks to Dana Gioia and the Dead Flamingo Society for their assistance in compiling this list.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)