Peter L. Stern introduces several notable characters in the Boston rare-book trade.

I have been asked to write a blog for the ABAA along the lines of “characters in the Boston book trade.” I hardly know where to begin, but I’ll give myself a pass and leave it to others to extoll my virtues and undisputed genius. My own career in the antiquarian trade started at the Starr Book Company on Kingston Street. This was very nearly where the Great Boston Fire (1872) originated, and our building was likely built on those ashes. It may have been 1972 outside, but inside it was a century earlier. We only had direct current, our heat came from a central Edison steam plant, and “air conditioning” was supplied by an industrial fan that sounded like a revving B-24. My morning’s first task was to sweep the floor and then pack shipments, which were bundled with string. Remember packages tied by string? My starting pay was a princely $100 a week, but given the modest business that paid it, I never resented it, although more than once, I was very nearly felled by book avalanches.

My boss, Ernie Starr, had been in the trade since the late thirties or early forties. He possessed a genuine enthusiasm and appreciation for books, even if he occupied a low rung on the ladder. He was originally in business with his brother Milt, a rather gruff man. Eventually, he and Ernie split up. Milt got Cambridge, Ernie got Boston. I particularly recall one anecdote Ernie told about their partnership. They bought a shop in Cambridge called “Tutin’s,” and along with the space, the shelves, and the stock, they got the old fellow who manned the place for decades. Very shortly after the purchase, the brothers walked in and noticed that the books on the new arrivals table had been drastically marked down. Asking their newly acquired employee about this, he replied, “Ah, Tutin got his money out of those long ago.” That was it for him.

After a couple of years, I left this nest and flew into the world I now inhabit, but I consider myself fortunate to have had the opportunity to become acquainted with so many memorable books and people. My first ABAA chapter meeting, attended at the invitation of Ernie Starr, was at the Sheraton Commander hotel near Harvard Square and so I was able to meet so many colleagues barely remembered now.

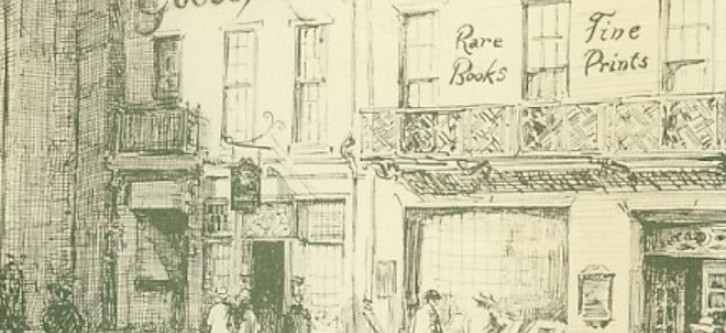

.jpg) Goodspeed’s Bookshop packed the meeting with their employees, each of whom voted as instructed. Eventually (not on that occasion), it was pointed out that each member gets a vote, not each person sitting at the table. By this tactic, the Boston Book Fair’s inception was held up for some years as Mr. Goodspeed apparently saw no benefit encouraging competition in what he took to be his bailiwick. I was never treated well by Goodspeed’s. I didn’t take this personally, my experience being a common one.

Goodspeed’s Bookshop packed the meeting with their employees, each of whom voted as instructed. Eventually (not on that occasion), it was pointed out that each member gets a vote, not each person sitting at the table. By this tactic, the Boston Book Fair’s inception was held up for some years as Mr. Goodspeed apparently saw no benefit encouraging competition in what he took to be his bailiwick. I was never treated well by Goodspeed’s. I didn’t take this personally, my experience being a common one.

I wasn’t there, but it was related to me how, on a very hot summer day, George invited a visitor to lunch. They stepped out into the street, where this other person took off his jacket. George stopped him, noting “that a gentleman does not take his jacket off on Beacon Street.” The fictional Late George Apley lived just down the hill, but had nothing on the late George Goodspeed.

For those unaware of it, for a number of years this firm issued a publication called The Month at Goodspeed’s, which remains for this writer the very model of good prose about rare books, and the finest bathroom reading any antiquarian bookseller or collector can have readily at hand (an observation: you can tell a lot about any bookseller by the reading material in their loo).

The late Maury Bromsen (photo at right), a wealthy man whose specialty was Latin America, would come in to Ernie’s actually crying about George Goodspeed keeping him out of the ABAA because he was gay. Eventually, he was admitted, and did the Boston Fair a single time. He set up display cases, blockading attendees at his booth entrance, interrogating them as to their interest. Maury sponsored lectures at the Boston Public Library, taking strict attendance. One Boston dealer asked me to tell Maury, if asked, that I saw them there (he would call and insist that I attend for his “genuine French champagne”). Sure enough, days after the event, he called asking me if they attended. I responded that, in fact, we had shared “a glass of genuine French champagne” at the reception (the irony was hopelessly lost). He called back, telling me that he had gone through all the pictures and still didn’t see them, asking me where they were sitting. I lied again, insisting that I spoke to them there and had no idea where they sat. Maybe Goodspeed had a point, but for the wrong reason.

This might not have been a Boston peculiarity, but many of my brethren were hostile to their local colleagues, refusing to show them books readly offered to out-of-towners. There were exceptions: Ernie for one, and George Gloss (whose Brattle Book Shopis run by his son, Ken Gloss) for another. I apologize to others not mentioned or recalled.

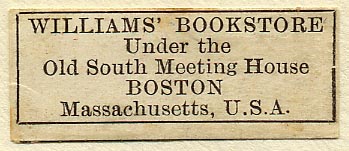

Every day I walk past the building which housed the Williams Book Store, run by Miss Williams (who had, at one time, been married to some minor Eastern European prince). Her boyfriend, who I think slept on the floor, was a formerly wealthy businessman (at one time controlling Western Union and the Boston Post), but by then down and out and suffering from being an alcoholic jackass. He’d come into Starr, wearing a shabby overcoat, pulling empty nip bottles out of the pockets, tossing them to me one after another to trash for him. I recall Williams (where our own Jim Cummins found himself when he wasn’t getting into a fight on the hockey rink) as a chaotic, almost sinister place. The prices were insane and fantastic. A two dollar book might have been a thousand. A five dollar book might have been marked fifty thousand. Anyone walking in was set upon by these vultures and was considered lucky to have escaped unscathed.

Every day I walk past the building which housed the Williams Book Store, run by Miss Williams (who had, at one time, been married to some minor Eastern European prince). Her boyfriend, who I think slept on the floor, was a formerly wealthy businessman (at one time controlling Western Union and the Boston Post), but by then down and out and suffering from being an alcoholic jackass. He’d come into Starr, wearing a shabby overcoat, pulling empty nip bottles out of the pockets, tossing them to me one after another to trash for him. I recall Williams (where our own Jim Cummins found himself when he wasn’t getting into a fight on the hockey rink) as a chaotic, almost sinister place. The prices were insane and fantastic. A two dollar book might have been a thousand. A five dollar book might have been marked fifty thousand. Anyone walking in was set upon by these vultures and was considered lucky to have escaped unscathed.

Miss Williams was preceded by her father, who was not of high repute himself. Ernie told me that, as a boy, he ran errands for a relative with a hardware store nearby. He was sent to Williams with a ladder and the strict instruction to either return with the ladder or $2.00. He returned with neither and was promptly sent back to retrieve the ladder.

There were various and sundry O’Neills and O’Neals. The latter were ABAA members who maintained a high quality inventory, and I’ll politely suggest that many found them difficult to deal with. Gene O’Neill operated as “in our time” from various apartments. He had very good taste and instinct, but lacked what we might call “people skills.” He operated semi-secretively, issuing catalogues that many will recall for the pornographic narratives springing from the feverish turmoil of his imagination. His brother, Jimmy, operated as the Temple Bar Bookshop (also an ABAA member), and suffered from, among other things, serious mental health issues. I chose to avoid him whenever possible. I think Jimmy did the Boston Fair once and Gene visited a single time. They had chips on their shoulders the size of cement blocks and were never able to realize the potential they clearly possessed.

Meanwhile, over in Cambridge, Jim Randall, who had been a college professor, traded as Ahab Rare Books. As mentioned earlier regarding our town, he hid his better offerings from the locals. A California dealer of our acquaintance would visit him, and take the T back over to Boston and sell me some of what he bought there. The few times I went there, Randall knocked back the better part of a bottle of Scotch in the time a lesser man might have dispatched a can of Coke.

Photo by Rose Lincoln (via Harvard Gazette)

They, and others unmentioned or not immediately recalled, were our people, and had more warts and idiosyncracies (and even the occasional good point) than I have room or inclination to relate (while sober anyway), but these ghosts were once three dimensional, flesh and blood, and deserve to be remembered in words beyond the simple sentiments engraved on their tombstones, or, for that matter, in those few I provide here.

Maybe it’s not much different elsewhere, but this is where I hail from. Lest I be accused of dwelling in the past, we enjoy an active book community here and recommend visiting, or as we traditionally refer to it, scouting. The very first resident of Boston, one William Blackstone (or Blackston, or Blaxton), arrived in 1625 with a trunk full of books, and people have been doing it ever since.

.jpg) Goodspeed’s Bookshop packed the meeting with their employees, each of whom voted as instructed. Eventually (not on that occasion), it was pointed out that each member gets a vote, not each person sitting at the table. By this tactic, the

Goodspeed’s Bookshop packed the meeting with their employees, each of whom voted as instructed. Eventually (not on that occasion), it was pointed out that each member gets a vote, not each person sitting at the table. By this tactic, the

Every day I walk past the building which housed the Williams Book Store, run by Miss Williams (who had, at one time, been married to some minor Eastern European prince). Her boyfriend, who I think slept on the floor, was a formerly wealthy businessman (at one time controlling Western Union and the Boston Post), but by then down and out and suffering from being an alcoholic jackass. He’d come into Starr, wearing a shabby overcoat, pulling empty nip bottles out of the pockets, tossing them to me one after another to trash for him. I recall Williams (where our own

Every day I walk past the building which housed the Williams Book Store, run by Miss Williams (who had, at one time, been married to some minor Eastern European prince). Her boyfriend, who I think slept on the floor, was a formerly wealthy businessman (at one time controlling Western Union and the Boston Post), but by then down and out and suffering from being an alcoholic jackass. He’d come into Starr, wearing a shabby overcoat, pulling empty nip bottles out of the pockets, tossing them to me one after another to trash for him. I recall Williams (where our own