The Antiquarian and Rare Bookseller Today:

The Decline of the On-the-street Bookshop and Its Consequence

Overheard at a recent book fair, one bookseller to another: “Business used to be a lot more fun.”

The role of the old, rare, and antiquarian bookseller has changed greatly in recent decades, from a rich brick and mortar presence in every major city of the U.S. to almost no physical bookshops on the street today.

In the 1970s and '80s, there were important bookshops centrally located in every major city of the United States. Many of these shops gathered in “book rows.” In New York, for example, there were dozens of bookshops on 4th Avenue alone. Presently there are, according to the ABAA, two large full-service antiquarian books in New York City: Argosy and the Strand. Of the 39 New York City ABAA booksellers, 29 are open by appointment only; of the 10 remaining who keep open business hours, six have offices, not storefronts. There are, of course, other booksellers, mostly used and out-of-print dealers who are not in the ABAA, but the ratio is undoubtedly similar to the above. At present, there is no large brick and mortar full-service antiquarian or rare bookshop on the streets of Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington D.C., downtown Philadelphia, or Dallas.

Booksellers now operate from home or office with few or no walk-in clients. The ability to meet potential new clients is limited to exhibiting in the expensive and competitive antiquarian book fair circuit where a bookseller has a temporary 10 x 10 space among the many other dealers also seeking to make new clients.

A few short decades ago, the local bookseller was the sole conduit between buyer and seller. In those days the bookshop was the only source where one could find a book, albeit through an extremely inefficient system of book searching. It was also the only place to have a book evaluated or to sell one's collection. Today, the antiquarian or rare bookseller’s existence has changed dramatically from the store-front presence to the internet bookshop and even the auction house.

Even several decades before the internet era, our antiquarian and specialist dealers were becoming less salesroom-bound and more research office-oriented. Instead of a store that has a welcoming clerk with open shelves that surround the sumptuous rare books room (a store model where many novice collectors, incidentally, would eventually find their way to the “inner sanctum”), the book trade has moved towards an unassuming office with clerks who look up from their cataloging with annoyance when a stranger walks in.

The American book trade began its transition from big box to small office long ago, in the 1970s, when the baby-boom generation produced its first disgruntled ABD (all but dissertations) refugees: those who left graduate programs due to the shrinking prospects for teaching and sought challenging careers related to their passions and interests elsewhere. Some highly educated men and women turned to bookselling as an alternative to teaching because their research and writing skills seemed to fit the requirements of the antiquarian business. While some went into the general antiquarian trade by working at bookshops, many gravitated to specialty bookselling where a storefront was not essential.

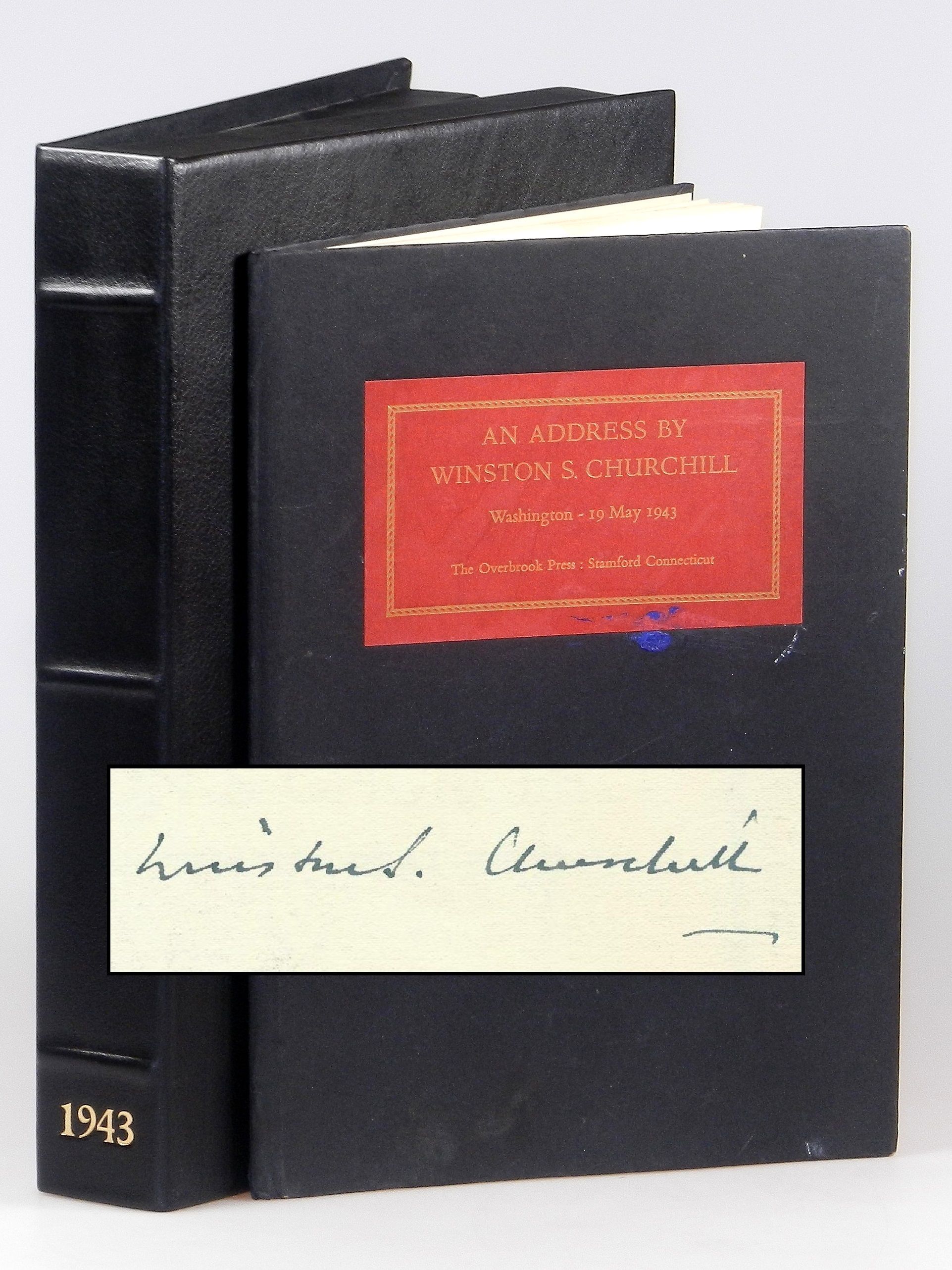

The rise of the specialty dealer found sellers who entered the book trade by focusing on a particular area instead of buying and selling all subjects and ages of books. With the small offices came the rise of the specialist and the demise of the great general bookshops. Specialists appeared to handle books on architecture and technology, on psychoanalyst literature, and on the history of medicine or science. Specialists appeared in music literature, in military history, in American literature, in Civil War studies, on Winston Churchill, in English books, then in 19th-century English literature, Charles Dickens, and on to many subjects ranging from children’s books to post-modern fiction.

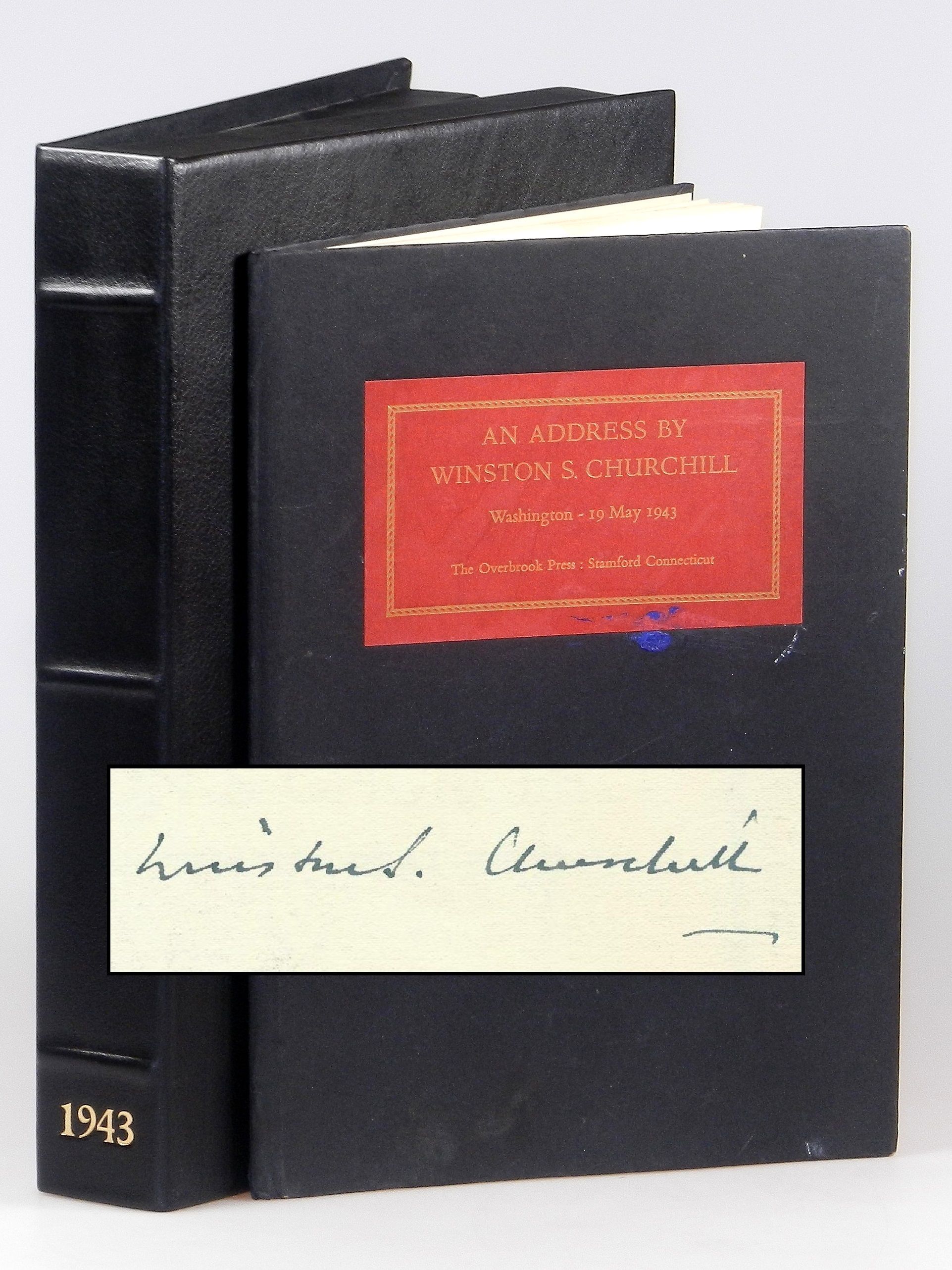

An Address By Winston S. Churchill Prime Minister of Great Britain Delivered Before Members of the Congress of the United States -- 19 May 1943, Signed by Churchill

Stamford Connecticut: The Overbrook Press, 1943. Limited Edition, signed. Hardcover. This is the scarce limited edition of Churchill's 19 May 1943 address to the U.S. Congress, the only copy signed by Churchill we have offered. Churchill's signature in black appears on the first free endpaper. This was Churchill's second address to Congress, seventeen long months of war having passed in the interval since his first, just after Pearl Harbor. (Offered by Churchill Book Collector)

The skills of the dealer have also changed greatly since the 1970s, a time when a large part of rare book knowledge was based on experience. With years of experience buying and selling books, the dealer developed an intuition much like the knowledge of the London taxi driver. In the days before GPS and Google Maps, the London cabbie could take his passenger to, say, Cecil Court, a street most people have never heard of, from anywhere in the city via the shortest route. In this same way, the antiquarian bookseller of the past managed to remember the identification points and current value of the many hundreds if not thousands of books handled over the years.

Nowadays, the dealer is likely to have much less faith in past experience. Instead, one turns to a computer to see how many copies of the book are available on the databases and their prices. If the book is very old, a check is performed to see how many other examples of the book are located in the libraries around the country, since an antiquarian book is often destined to be sold to a library. The dealer must now determine quickly if the book is too common to buy at all. A modern bookseller is now likely to carry a wireless notebook along when visiting a book fair or bookshop where OCLC, ADDALL, KVK, and other databases will be consulted before a purchase is made.

The second quality that characterizes many contemporary book dealers is research skills. A 17th or 18th-century book, if it is not a “high spot,” will need to have its complete form identified and verified and its historical context documented. Often this information is not provided because the bookseller does not have the correct training or the correct reference works to do so. In the antiquarian book trade in America, booksellers need no particular training or certification. A true “antiquarian” bookseller is willing and able to provide full bibliographical and contextual information on the books he or she sells. Providing identification and correct historical context is a major component of the research of a good bookseller, and it occupies much more time than any other part of the job description.

All the dealer needs today is an office, a telephone, a fast internet connection, and a good university library nearby. Now, the bookseller constantly scans all the catalogues posted on viaLibri, in Fine Books and Collections, on A&E Gallery, ILAB, Bibliorare, as well as those that come in the mail. More and more auctions are now available in real-time, so that live bids can be made for an auction in Munich, then an hour later in London, then later still in New York. While this obviously imperfect method does not allow a dealer to physically inspect the merchandise, it does bring one in touch with a wider range of materials than ever before.

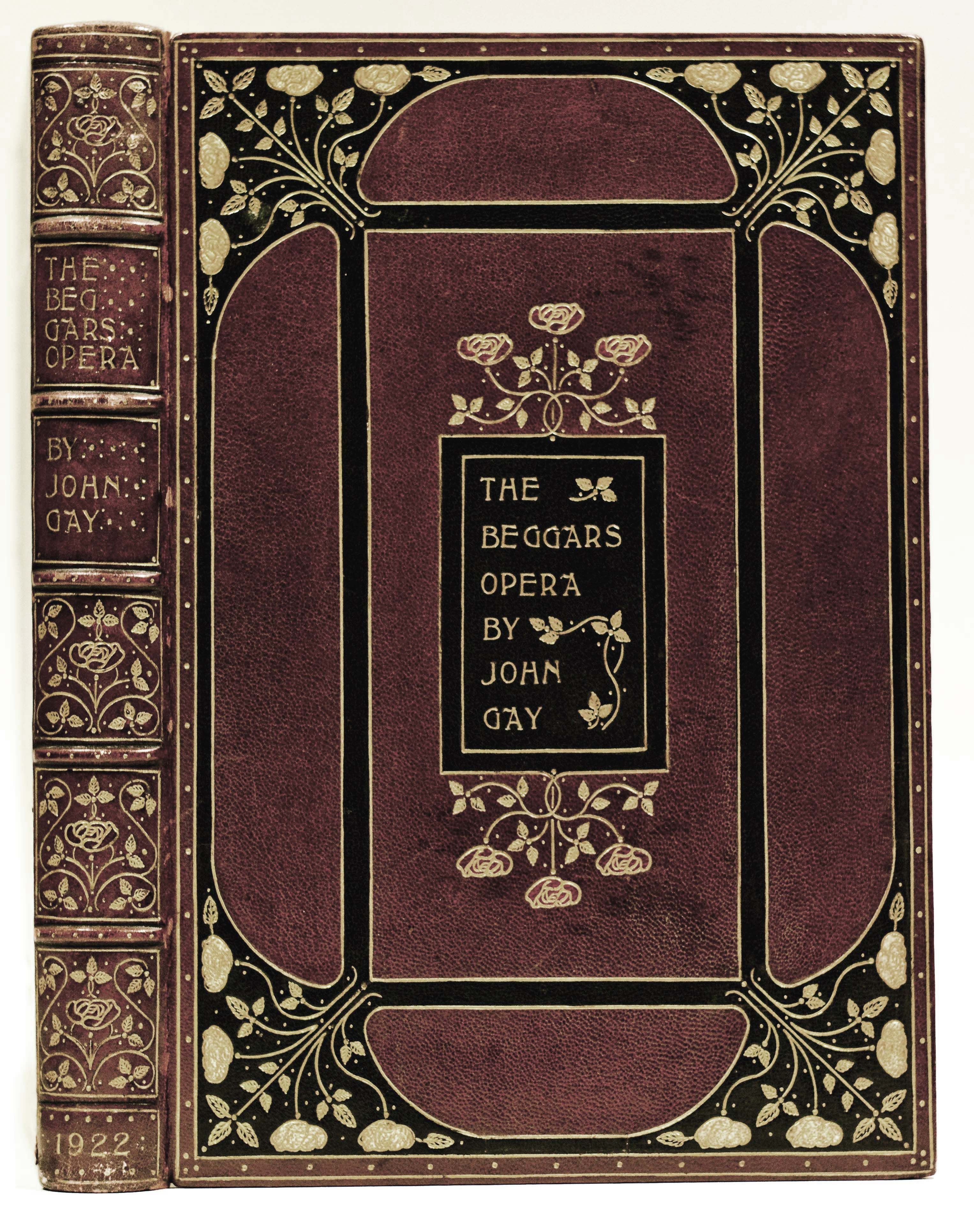

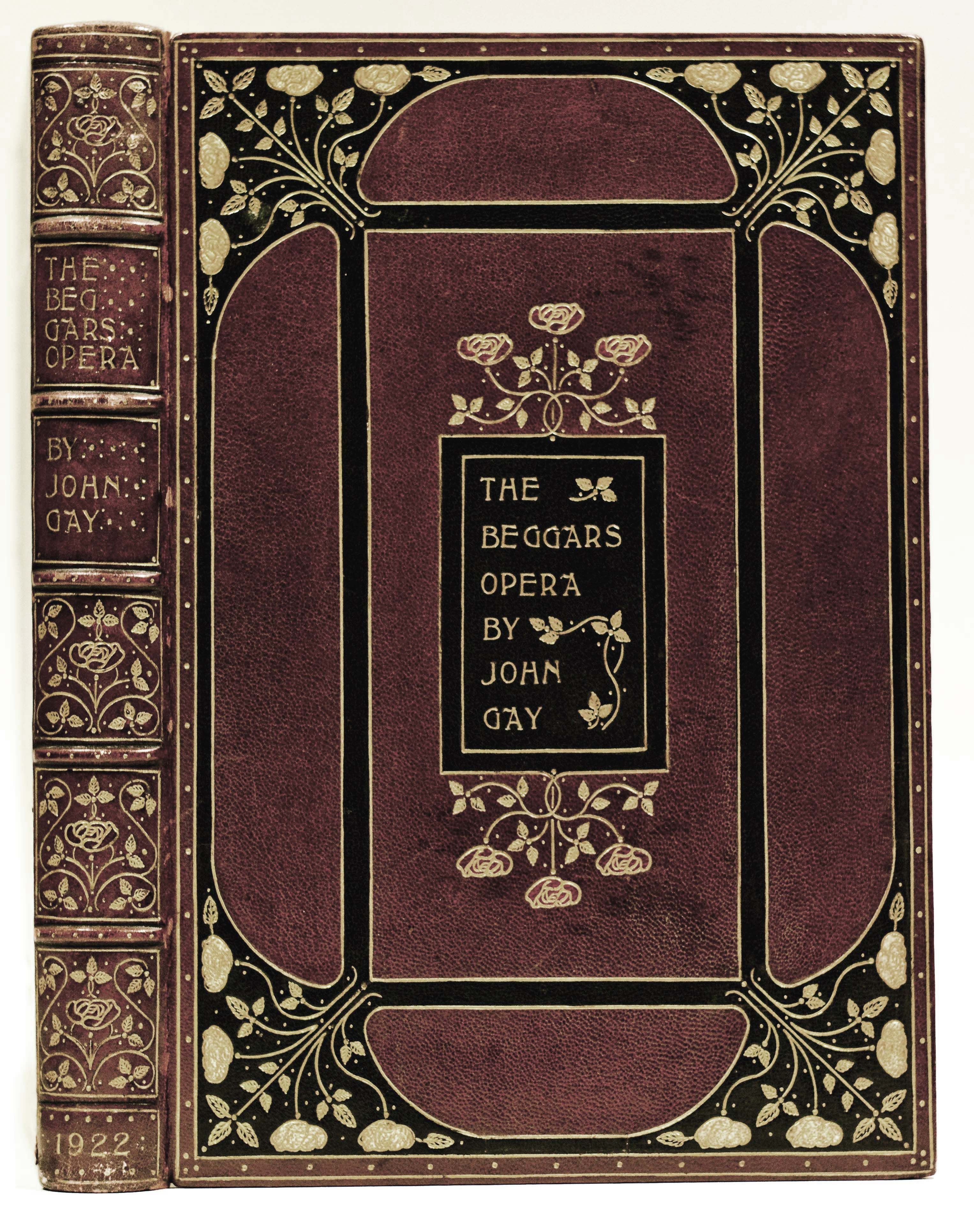

The Beggars Opera

by John Gay

London: O’Connor, 1922. Introduction by Oswald Doughty.Twenty-Eight Plates in Collotype and a facsimile title of the first edition. Limited edition.With four 18th century engravings, not called for, of the play characters. With a rare English binding from the 1920s. Full brown morocco, inlaid with art-deco decorations in black gilt and red. Desiged and hand-tooled by H. Brown, forwarded by A. Warnock. Bookplates of “HB” [H. Brown?] and Jeffrey Stern. (Offered by Golden Legend, Inc.)

The Rare Book Community

Ours is a self-regulating community that discusses and evaluates not only the books but also the booksellers: a small and tight knit group that gathers at book fairs, in bookshops, at lectures in libraries, and at meetings of book clubs where we discuss our collections and the rest of the community, for better or worse. Since we work with rare and specialized material, it is very important that we share information.

At its worst (or perhaps its most defensive), the community forms opinions about the people involved: about this collector who will not let anybody else buy an item at auction; about that collector who pays for purchases immediately and the other who takes forever to pay (and then can only be trusted to pay in cash). A librarian at a local university is a “good” guy when he always buys from the local dealers, while another will not give the time of day to anyone who doesn’t have an Oxford or Cambridge accent. One dealer has a reputation of pricing things fairly (read inexpensive); another is a “quintupler” (marking the book at five times his cost). One dealer is known to have torn apart books to sell the engravings or maps, yet another has helped to catch thieves who steal manuscripts.

This community is likely to continue even in the face of technology and new diversions. The old book will continue to be valued and loved as a symbol of ageless intelligence and as a source of a multiplicity of historical studies. The young American dealer of today, and those who come into the field in the next decades, may find themselves in an enviable situation if they take time to develop the knowledge and then become part of the small but supportive rare book community of dealers, collectors, and librarians.

--Gordon Hollis

Golden Legend, Inc.

----

Read part 1 of this survey of book collecting in the USA...