Book Collecting in the United States:

A 21st-Century View of Our Collectors, Our Research Libraries, and Our Booksellers

While the antiquarian book community is very small worldwide, it has been in the United States, the tiniest of them all, until very recently. Among all the cultures around the world who have written and read manuscripts and printed books in their variety of forms, North American literacy and book production occurred centuries if not millennia after those of predecessors like the Chinese, Greek, Hebrew and Mesopotamian, Indian, Mexican and Central America peoples. 1

As our many settlers came to North America and found homes, books were often left behind, either in the “old country” or before an arduous journey across the land. A bible, sacred book, or a family memento might accompany the traveler, but not a heavy, cumbersome library. Also, in early America, libraries and bookshops were few and far between. Overall, books remained a very minor part of life in this country until the end of the 19th century, when printing technology made the book widely available and accessible due to machine-set type, machine-rolled paper, and a perfected method of binding. As a result, we Americans as a whole have little knowledge of old books or printing history.

Until recently, there was only a small group of serious book collectors in America. These collectors acquired antiquarian books and manuscripts, especially on the subjects such as travel and exploration of America, Greek and Latin classics translated into English, monuments of English literature, books with colored engravings, and highlights of early printing.

Collectors like Henry Huntington, J. Pierpont Morgan, and A. W. S. Rosenbach (bookseller to the wealthy) formed large collections that often became rare book museums. Other collections like that of Robert Hoe III were dispersed at auction. Overall, the antiquarian book world was tiny in significance compared to those in other countries until after World War II.

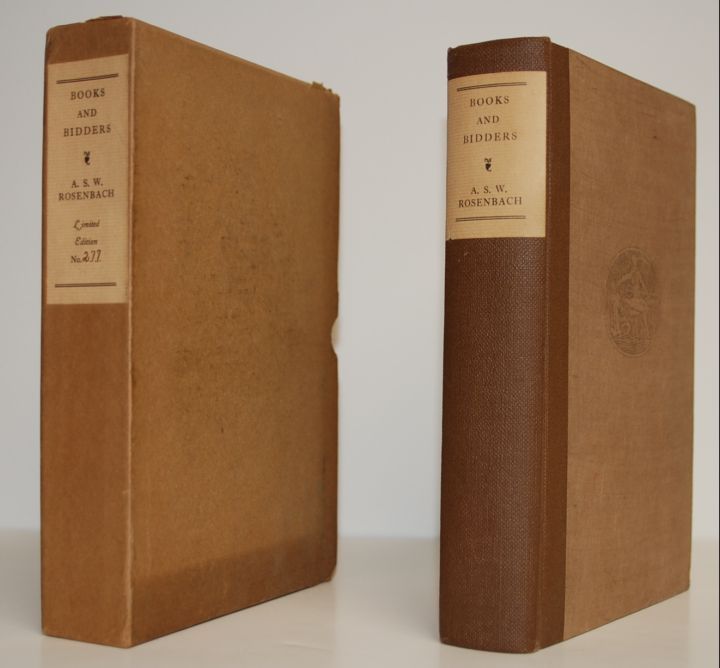

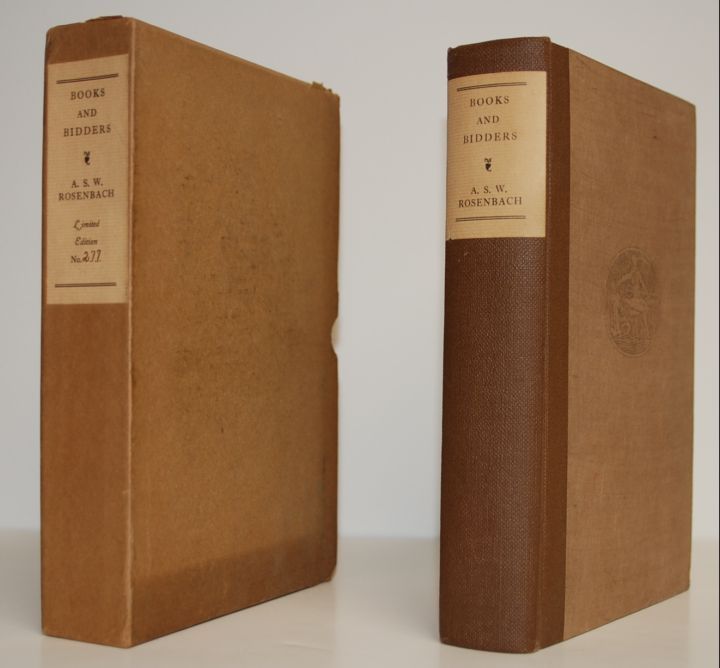

Books and Bidders; The Adventures of a Bibliophile

by A.W. S. Rosenbach

Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1927. 1st. Hardcover. Fine. One of 785 hand numbered copies signed by the author and bound in publisher's original brown quarter cloth and tan boards, front panel embossed, paper label on spine printed in black. Top edge gilt. Frontispiece page of the Gutenberg Bible, showing the ten commandments, in color. Over 85 illustrations throughout in black & white. Housed in a tan slipcase with paper label on the spine printed in black and numbered by hand. (Offered by James & Mary Laurie Booksellers)

The “Modern First” Collector

Something unexpected happened to the world of book collecting in the 1960s. It began when the modern first edition market came alive with a “howl.”2 The modern first edition can be defined as the first published editions of some of the 20th-century authors who were popularized in college classrooms as being avant-garde or “modern” (i.e. differentiated from the Romantics and the realists in their worldviews). A few 19th-century authors were "grandfathered" into the modern movement, such as Thoreau and Whitman. Since condition was of the utmost importance, the modern first edition was not to be read, and only the first edition represented the book as it came into the world. Generally, the second edition is worthless. A preference, later an extreme preference, was given to limited editions, signed and inscribed books and, most of all, to the condition of the dust jacket when a book was published with one. The dust jacket of the first edition of The Great Gatsby (Scribner, 1925) could outstrip the value of the book it covered by a hundred thousand dollars.

Beginning in the mid-1960s and ending within the last decade was a spectacular growth of edition collectors. The sudden and surprising growth of this market brought a pronounced explosion to the sleepy world of book collecting. In the 1960s, few institutions and fewer collectors cared about 20th-century novels and poetry; now, all was changed. The modern first edition collector brought fashion, excitement, and adventure into book-collecting for the first time in decades, maybe the first time in centuries.

Bright young men and women were coming into bookshops looking for first editions of novels by John Steinbeck and Scott Fitzgerald; broadsides by Robert Creeley; new work by Sylvia Plath; gaily printed small press editions by the Black-Sparrow Press; letters written by W. H. Auden, Henry Miller, and Anaïs Nin; hand-printed editions by Henry Miller, the Hogarth Press of Virginia Woolf, or those of the Paris presses of Edwin Titus and Sylvia Beach.

While older collectors, few as they may have been, still valued the traditional figures of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, and Petrarch, as well as Goethe, Cervantes, and Corneille, younger collectors were no longer looking for the classics, whether in their original languages or in translation. Our college curriculum had turned its back on the classics (Latin or Greek was no longer required in college and Hebrew had long been abandoned except in religious schools). Young book lovers and collectors were looking for lively writers who spoke directly to them, without couplets, about the world they knew, not about ancient gods.

Although neither antique nor rare by any numerical count, modern first editions were starting to sell in bookshops of the time, like the Phoenix in New York City and Serendipity in Berkeley. Collecting extended from books to little magazines and ephemeral broadsides and posters. The objects were read and prized. The flimsy throw-away broadsides of Ed Sanders and Robert Bly were prized. Also collected were the limited editions of the expatriate presses like Three Mountains and the Obelisk Press of Paris and the privately printed books of D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce, particularly when signed or in very fine condition and, especially, in their fragile and often garish dust jackets.

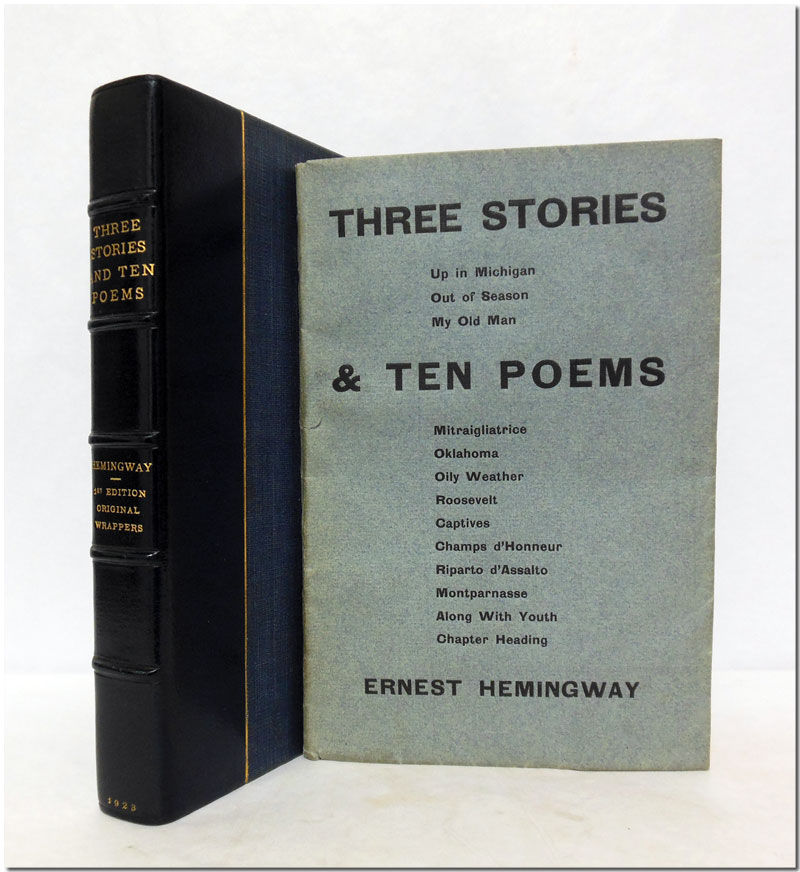

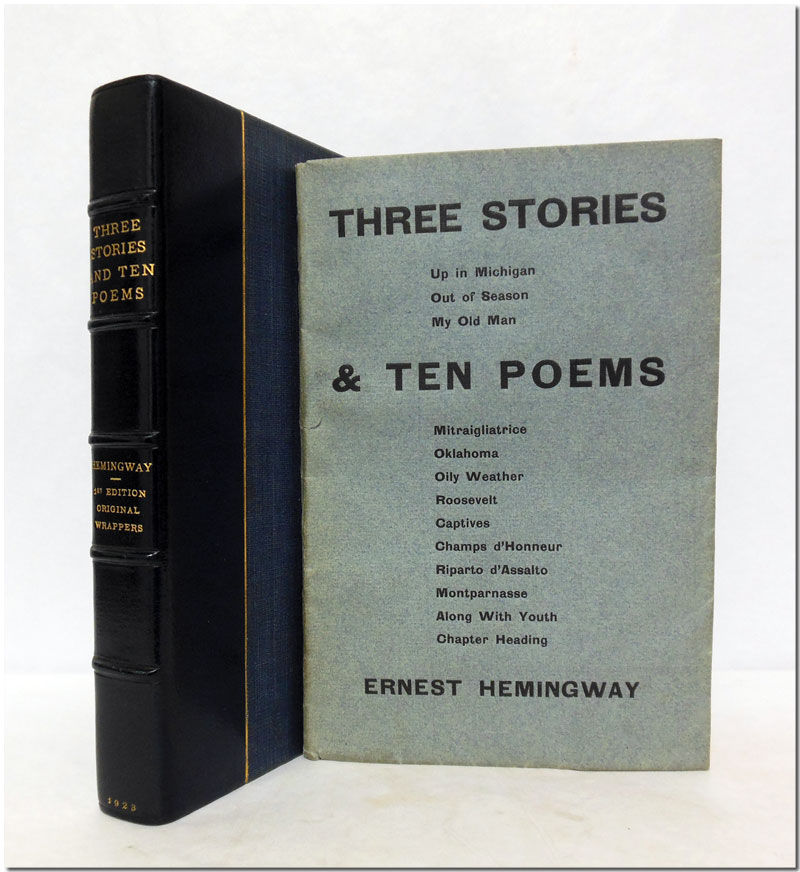

With the number of collectors interested in “modern firsts” growing, the values started to rise. It has, as we all know, far outstripped the standard book-collecting fare of generations past in many areas (manuscripts excluded). The market began its very public ascent with the landmark first edition auction of the Jonathan Goodwin sale at Sotheby's Parke-Bernet in 1977, where, for example, a first edition of Hemingway's Three Stories and Ten Poems inscribed to Sylvia Beach of the Press of Shakespeare & Co. sold for an astounding $6,000. This ascent continued through the end of the century when the exact same copy sold at the Neville sale in 2004 at Sotheby's for $150,000.

Three Stories & Ten Poems

by Ernest Hemingway

Paris: Contact Publishing Company, 1923. Publisher's pale blue wrappers, printed in black, fore and bottom edges untrimmed. Hint of slight tanning at edges, minuscule nick (no loss) in upper wrapper at spine, otherwise about fine. Half morocco folding case and fleece-lined chemise.

First edition of the author's first book -- although only the sequential nature of the volumes in the Three Mountains "Inquest" series prevented _in our time_ from preceding it. One of 300 copies printed in Dijon by Maurice Darantiere. Six of the poems had seen prior publication in POETRY (Jan. 1923). The short stories -- "Up in Michigan," "Out of Season," and "My Old Man" -- are here first published. "Up in Michigan" was not reprinted until 1938, and then in somewhat revised form. The other two stories were reprinted in the 1925 Boni & Liveright IN OUR TIME.

"No other writer ... [in the Modern Movement] stepped so suddenly into fame, or destroyed with such insouciance so many other writers or ways of writing or became such an immediate symbol of an age" - Cyril Connolly, The Modern Movement. (Offered by William Reese Company)

Values rise in the field of first editions as a growing demand outstrips a sluggish supply. With a great number of collectors interested in the modern literature field, it is possible to understand how a minor collection of stories by Hemingway, with many private and institutional buyers, could sell at a higher price by far than a first edition of John Milton's Paradise Lost, a rare and major book, but one with much fewer bidders.

These days, the modern first edition market does not seem to be growing at nearly the same rate as before. The slowdown is, perhaps, because younger people today do not respond to the “Lost Generation,” but are faced with their own adrift futures; or perhaps because the modern novel is no longer read or no longer read in book form. Hemingway can now be read on a tablet, if he is read at all.

Collecting “Great Books” of Western Civilization

While there are some who understand that America has a composite history formed by settlers from all over the world, our educational system has taught us that Greek, Roman, and Western European thought are at the root of our intellectual and industrial development. A consciousness of “great books” has followed the teachings of our schools, through which a canon of thinkers has been identified over the centuries as authors of “great” or “touchstone” books (to use Matthew Arnold’s phrase), which are key to our intellectual and scientific development. Each year, there are numerous rare book exhibitions in libraries featuring great works in history, science, American literature, English literature, French literature, and so on. Then there are exhibitions of “100 Great English Illustrated Books,” “100 Great Children's Books,” “50 Important Travel Accounts,” and many others to be found in the exhibition links of libraries and of magazines like Fine Books and Collections.

Some of the same collectors who created a market for modern literary first editions moved to Western “great” books, perhaps growing either a bit bored by 20th-century first editions with their similar formats and lack of complicated bibliographic challenge or perhaps traumatized by extremely high prices for modern books (or to be precisely accurate, high prices for those with a perfect dust jacket or an important inscription). Whatever the reasons, collectors came to feel as they do today: that "great" books in their first editions and original bindings are artifacts that possess both cultural and monetary value.

While a few of these historic editions had always appeared at book fairs, it did not take long for more and more to appear. Presently, a great deal of the book fair landscape is flowered with blue-chips of every variety and species.

One other fact needs to be mentioned: the auction houses, especially the major auction houses, began a campaign in the 1980s to reach private collectors directly through glitzy catalogs and expert staff, some of whom came from the book trade. Prior to this time, the auction house was historically a conduit to the book trade. Dealers made up the major buyers, as private collectors often bid through a dealer and pay a commission for the expertise and the added convenience of not having to attend in-person.

Auction houses found that “great” books were the perfect vehicle for their purposes. For the auction house, these books were relatively easy to market to a general audience because their importance was well understood. The values of “great” books were substantially higher than those of modern firsts. Auction houses could also play one card that the dealer could not: they could suggest that the price paid at auction was the fair-market and not the retail; hence, the book could be sold in the future at the fair-market value of the time, which has always appreciated.

Aside from the fields of modern first editions and “great” books, several other book-collecting areas have grown in recent decades. Interest in female authors has been important since the 1980s. Private collectors are beginning to look for the fugitive LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) material. The comic book has come into its own through the graphic novel and movie scripts. Books on photography have been very popular when original prints are included.

Also popular with collectors is the “book as object” field. Thirty years ago, there was some interest in the shape, design, and artistic printing of books. Many collectors liked the “finely printed” book: the American Grabhorn, Arion, and Perishable Presses; the English presses of the William Morris school: Doves, Kelmscott, Ashendene, Golden Cockerel, Gregynog, and a few others.

Although no longer the only way to read a text, the book remains a potent symbol of learning, intelligence, and civility. As a symbol rather than a text, the book form can be used in an artistic way wherein it retains its power, separate from the text. In short, the book form itself can become a canvas for artists with or without the text. Art historians among present-day collectors are evident at conferences like the Codex Foundation with its book fair in San Francisco, which draws almost as many visitors as the august California International Antiquarian Book Fair across town.

Looking toward the future, we must face the fact that the function of the book may be changing in the same way that the manuscript changed. By the end of the 15th century, the printed book could be produced faster and its multiple copies distributed farther than a unique manuscript. As a result, the manuscript form fell out of general use, although it became the perfect vehicle for artists who illuminated and decorated texts for the pleasure of rich patrons.

Our Research Collections

By the 1970s, with money awash in our public library and university systems and low prices in the antiquarian book world, seemingly every research library across America was buying rare books for their collections. Aside from major research libraries like Yale, Harvard, University of Illinois, the New York Public Library, and University of California, Berkeley, state colleges and small universities also jumped into the mix. One today can see the result of institutional collections by finding a copy of the out-of-print and woefully missed Guide to Subject Collections in American Libraries by the late Lee Ash, which was first published in 1958 with multiple successive revisions. The Guide contained over 600 pages of listings with an astounding range of rare book and special collections across the country and in Canada.

Today the institutional backbone of the antiquarian community has succumbed to the degenerative ailments many old creatures develop. It has shriveled in some places, stopped functioning in others. Now, active rare book collections are found only in the major university research libraries of the East, a few in the Midwest, and a few in California. Also still active are the private libraries and museums like the Pierpont Morgan in New York, the Newberry in Chicago, and the Huntington in Pasadena. The number of public libraries that actively develop their rare book collections can either be numbered on one hand or limited, realistically, to one: the New York Public.

We have watched the decline in rare book acquisitions due to the rising costs of rare material and waning interest among younger faculty who can now use available library resources that the generation before could not. More recently, there has been a rush toward reallocation of library funds toward digital services. Today, fewer acquisition librarians appear at international book fairs. Academic orders from bookseller catalogs, once the bread and butter of booksellers, have plummeted. Written or emailed solicitations from dealers are frequently unanswered.

This is not to say that libraries have stopped acquiring books. Among libraries that do have endowments and budgets for rare book acquisitions, many are severely limited compared to several decades ago. Acquisition policies have also changed. Many libraries, for example, will not add an item that fits perfectly into their existing collection if another copy exists within driving distance. While this policy of one copy per city or region has a frugal logic, it changes the definition of a book from a physical object with its own unique fingerprint to that of a text identical to other copies of the same edition. By considering any text to be identical within the same edition, important considerations of book history, such as annotations, variations in text, and binding styles (which are often indicative of ownership class), are excluded. The door is also opened to having no actual example of the book at all when a facsimile or an electronic version is available.

Some libraries, though fewer than ever before, are fighting to keep their collections growing in spite of duplication or cost issues. For the Oscar Wilde collection held by UCLA’s William Andrews Clark Library, an item missing will be considered for purchase even if another copy exists at the Huntington (a mere 16 miles away). The raison d’être of the Clark’s Wilde collection is to have the original objects available on-hand for scholars to use.

During the present decades, we are seeing a great reduction, even abandonment, of acquisition programs in Western antiquarian and “great” books. It is hard to imagine that a great interest in, say, the Latin poetry of Terence continues to exist in America. It is one thing for the Newberry Library in Chicago with the best Terence collection in this country to abandon its acquisitions; it is another for a state university like California State University, Northridge to continue.

Even if there is interest in collection development due to faculty requests or endowments, it is becoming difficult to find experienced acquisitions libraries who know anything about the values of antiquarian material. The attrition of librarians who have retired after 30 to 50 years of experience has been devastating. New librarians in the rare book and special collections departments often have little experience in buying four-figure objects, let alone anything more expensive.

The library community, nevertheless, is very interested in developing in more current (and often less expensive) directions. Archives and book collections that chart our current languages and literatures, our technology, our late 20th-century cultural changes, if they are preserved at all, will find their way into our institutions through donation and purchase. Special collections such as the hip-hop archives at Cornell, avant-garde art at Yale, graphic novels at the University of Chicago, science fiction at the University of California Riverside, California opera at Stanford, left-wing political broadsides at Temple University, and dozens of others attempt to carry on with their institutional missions. One is happy to see the occasional collection development devoted to books from other cultures like China or Middle America. As the academic mission changes, so do the research tools.

You can read part 2 of Gordon Hollis' survey of "Book Collecting in the United States" here...

----

Notes:

1. Books published before printing, whether with wood-block printing or written by hand, are certainly antique and require description, but are not included in this discussion because they are now rarely in the general marketplace and the tools needed to analyze them are different from those needed for the printed book. While publishing has been done in many other countries (including those in Asia, the Middle East, and in the Southern Hemisphere), the main emphasis of book collecting among American collectors and U.S. libraries has been the Western antiquarian book and manuscript. <return>

2. *Allen Ginsberg’s Howl—considered important in the writing of Beat Generation—was published by City Lights in San Francisco in 1955. <return>