Fight of the Century: Auction Houses vs. Dealers

Editor’s note: Greg Gibson of Ten Pound Island Book Co., a specialist in “wet books” (maritime books, manuscripts, ephemera, sea charts, etc.,) has for the past five years authored a weekly blog chronicling his life in the rare book trade. Because he is smart, observant, witty and outspoken, and because he is a gifted writer (the author of several books) Bookman’s Log makes for great reading on many topics of interest to antiquarians – market trends, the effect of the internet, reviews of book and paper shows, and sundry anecdotes about fellow dealers and collectors.

In the past, Gibson has made passing comments on the undeclared war between dealers and auction houses, but those were mere shots across the bow compared to the anti-auction cannonade of his last two contributions. Although many dealers and auction houses work together on all sorts of levels (referrals, consigning, bidding, cataloging) the two groups are joined in basic competition for the material being offered and for the clients who might buy that material. When the stakes are high, this competition can become fierce.

Book dealers and auction houses each offer certain advantages over the other. A dealer can engage in a relationship with a collector, get to know what that collector needs, scout up material and offer it directly, advise the collector, and so forth. This increases the level of trust between dealer and client, and friendships often result. An auction house can do none of that. Auction houses might point out an upcoming item to a prominent collector, but cannot directly offer material. On the other hand, there is the chance that the collector will get it for less at auction than from a dealer.

The competition for saleable material falls along the same lines of argument. A knowledgeable dealer can offer much more personal service in terms of either consignment or outright purchase, and is more likely to take on entire collections and not just the high spots. Dealers can spend more time researching and marketing the material, and oftentimes have a deeper understanding of the material, its significance and market worth than do auctioneers. A case in point occurred recently when, on behalf of an old friend, I consigned to a major New York auction house two Bob Dylan song manuscripts. The presale estimate of the two songs was $40,000-60,000 in total. The auction house did zero publicity, blurred the photos in the catalog for fear of a lawsuit from Dylan’s lawyers, and botched the cataloging of them. Both were passed lots. After the auction, I found a buyer and sold them for my client to his satisfaction. On the other hand, if two well-heeled Dylanophiles were in the rooms that day, the price might well have gone into the six figures. That’s the auctioneer’s argument: you never know what might happen.

But what caused Greg to start stumping around on the deck, yelling like Captain Bligh on a windless day?

----

Recently, at the New York Antiquarian Book Fair, a colleague with whom I'd done a great deal of business over the years told me a remarkable story.

He had a wealthy, impulsive, and very skittish customer who had become convinced that all dealers were, to a greater or lesser degree, stacking the deck against their customers, and that auctions were the only fair and transparent market.

It makes sense intuitively – people competing openly against one another rather than trusting any single individual. Market price is determined by whomever will bid the most for an item, and that price is a matter of public record, therefore, transparent.

Certainly, auction rooms have been vigorously promoting this view, and venues like Rare Book Hub, for example, publicize auction houses while suggesting that private dealers are inefficient and obsolescent, if not downright untrustworthy.

But back to my colleague and the wary customer. Inevitably, as his high opinion of auction houses solidified, the customer began buying exclusively at auction. My colleague had a great deal of interesting material to offer this fellow (some of which he'd bought from me) but was completely frustrated by the customer's steadfast refusal to deal with a “middleman.”

So my colleague went into partnership with a prominent auction house, which purchased an interest in the material he had intended to offer to his customer. Obviously, the plan was for the customer to purchase the material at a forthcoming auction - probably at prices considerably higher than my colleague would have asked – completely satisfied that he'd cut out the middleman (my colleague) and had made his purchases in the most open and transparent market. For that privilege he would also pay the auction house a 25% buyer’s premium over and above the hammer price.

The story was typical book fair gossip. But here's the takeaway:

While it is easy to point to the Internet as the major game changer in our trade over the past few decades, the rise of the auction houses has been every bit as disruptive to what once passed for the norm. Auctioneers have been wildly successful in promoting themselves as the only fair and transparent venue, and now that they've gained dominance they've begun to squeeze – with buyer's premiums averaging 20-25% and sometimes higher, and with an ownership stake in more and more of the material being offered for sale. When I started in this business in the 1970s, established dealers could routinely expect calls from estate lawyers, collectors, or institutions interested in selling material. Now it is not so routine. And it is the combination of the internet and auction house aggression that threatens the delicate ecosystem of the rare book trade. I for one do not think customers are better served by auction houses, and I’m not so sure estate lawyers and institutions are, either.

Editor: Gibson probably did not think his snarky dig at Rare Book Hub would elicit a response, but Bruce McKinney, the founder of Rare Book Hub, formerly Americana Exchange, took up the challenge, and wrote a rebuttal to Gibson, where he offered “no apologies here.” McKinney’s point is that the greater the “disparity” between auction results and asking prices from dealers, the more likely collectors are to trust auction houses.

Rare Book Hub, founded in 2002 as Americana Exchange, has been enormously helpful to both collectors and dealers alike. McKinney, its founder, is himself a committed collector and rare book enthusiast. One feature available to subscribers on the site is a searchable database not only of past auction records going back to the beginning of the 20th Century but also of major dealer catalogs. For bibliographical and market research, this database stands head and shoulders above the rest.

Gibson was clearly delighted that McKinney had engaged him in this discussion and devoted his next blog to the subject.

Big day for me yesterday.

I was featured in an article in Bruce McKinney's “Rare Book Monthly.” In fact, I got a mention “above the fold” - in the lead text appearing on the home page. Even better, Bruce McKinney referred to me as “ABAA commentator Greg Gibson.”

I've never been called a “commentator” before, and I like to think that term confers a certain dignity lacking in the “jackass” and “loudmouth” appellations I usually endure. Walter Cronkite was a commentator. When commentators speak, people listen.

In an attempt to defend himself against my charge that he was a shill for the auction houses, McKinney quoted from last week's blog entry at considerable length. The anecdote I presented was an example of an auction house colluding with a dealer against the interests of a buyer - anything but the honest, efficient, transparent brokers McKinney has in mind.

Since there was no defending auction houses on those grounds, McKinney chose to critique my article thus:

In Mr. Gibson’s account a collector that buys only at auction and a dealer and auction house collude to get the collector to pay more at auction than they would privately. What he is actually suggesting is that some collectors are stupid.

Yes, Bruce. That is what I am actually suggesting. Some collectors are stupid. Ours is a complicated trade, and no one – collectors, dealers, auctioneers or commentators – gets it right every time. I think even you would agree that trusting in the transparency of auction houses rather than buying from any dealer, is not exactly the height of genius.

McKinney continues his defense:

Auctions loom large because the disparity between dealer prices and auction realizations has grown so extreme.

Now that, my friends, is where Bruce McKinney and Rare Book Hub jump the shark. I invite him - or anyone with sufficient time to waste - to compare the prices of items I have on offer with auction records for recent sales of comparable items. In most cases, mine will be cheaper.

The thing I most dislike about auctions – aside from the fact that they've convinced people that they are the most transparent and efficient market – is that they're too damned expensive. And they're often too damned expensive because the thrill of being an auction room bigshot tends to attract people with more money than brains. Which skews the market, as far as I am concerned.

All that said, however, I did post a reply in the comments area below Bruce’s article (as “commentators” are wont to do):

Bruce:

Thanks for keeping this always interesting discussion going. I'll stand by my observations – I think they're self evident - but must note that I usually preface my "McKinney is anti-dealer" rants by praising the database you've created. It's far and away the most useful tool available to dealers, and the reason I maintain my subscription to RBH. - Greg Gibson

I look forward to reading Bruce McKinney's rebuttal to my rebuttal in next month's “Rare Book Monthly.” His lead sentence should read something like, “Big day for me last month. I was featured in an article in Bookman's Log by ABAA commentator Greg Gibson.”

Editor: Gibson’s most-recent blog details a significant find amid a cache of old documents, and illustrates the real relationship between dealer pricing and the hot-house effect of an auction.

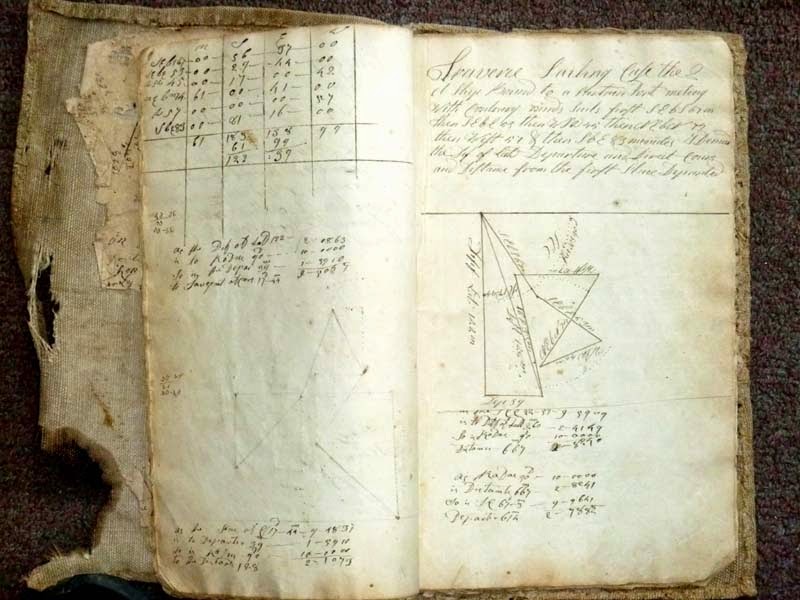

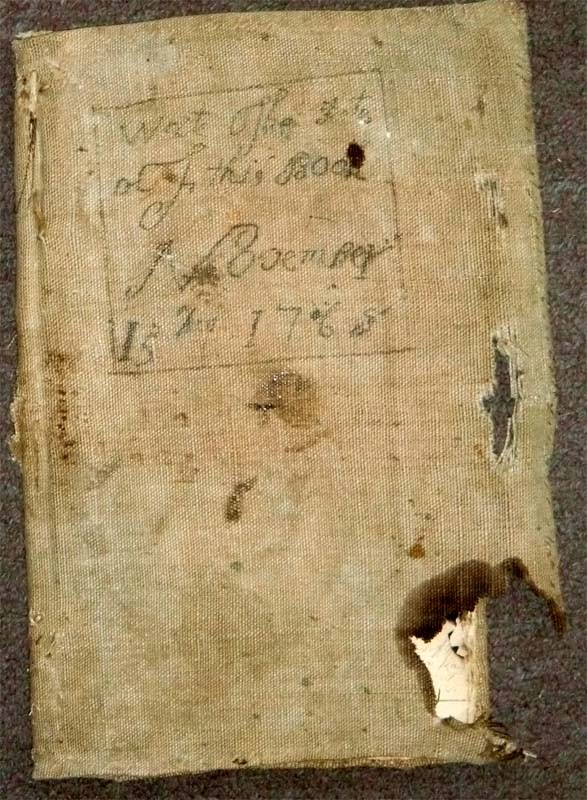

Yesterday afternoon I was diligently working my way through a stack of relatively undistinguished manuscript items.

I'd already cataloged Captain Clement Ryder's account book for two coasting schooners – the “Velocity” and the “Columbia” $150; "Abstract Log Ship 'Carlisle Castle' on a Voyage from London Towards Melbourne. Commencing May 23rd 1885, Ending Aug 31st 1885... Kept by Arthur F.B. Portman 2nd Mate." $350; and “Accounts of Coasting Schooner James Martin, 1870 – 1872.” $150.

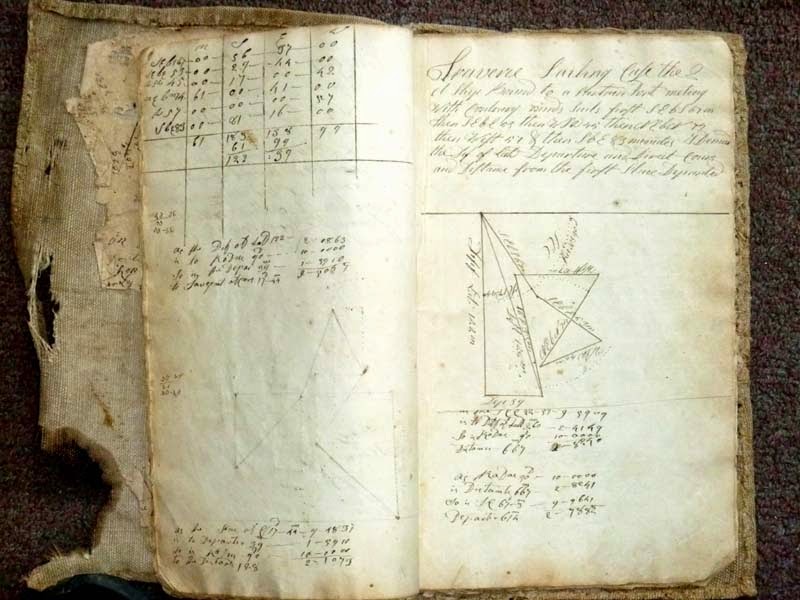

The next item in the stack was a raggedy, chaotic mishmash of an old navigation lesson book and a couple of scribbled log entries from...

Wait a minute. 1772? And look at this, right on the first page - “Saw a spalmeccty could not come at her the wind S & E we sald & got one porpoise...”

.jpg)

An American whaling log from 1772!

And in a single lovely moment I ceased trudging through the valley and was surveying the world around me from the pinnacle of another big hit. It had been sitting on the floor of my office for the past two months in a pile of junk.

I love this business.

---

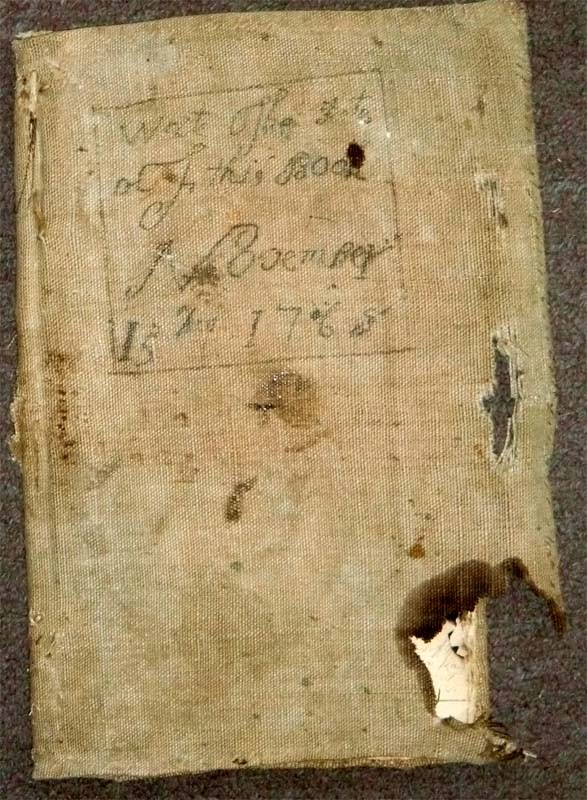

Manuscript. Whaling Log of "Good Sloop Dolphin of Boston Isaak Freeman Commander 1772 Wrote by Zenas Phiney.".Folio, unpaginated. Fifteen pages of manuscript entries.

This is the daily log of an early whaling voyage not documented by Lund or noted in any other reference source. It records a voyage off the Western Islands and "from the Grand Banks to Cape Cod" from the end of May to the beginning of October, 1772. The log begins with a faint, and difficult to decipher, list of the crew. The first entry is May 22. Daily entries give names of vessels and captains, and there is much talk of ships spoken and who got and did not get whales. The "Dolphin" catches a porpoise and chases a sperm whale. Then on "SaterDay 27 Day of June 1772. Fine weather Saw plenty of whales chast most all day but cold not strike till a bought 7 a clock we got aught and struck one." On July 1 "We finished triing out our whale which made 80 barrals." A week later Phiney reveals his status as a colonial, "As wrote July 8 day 1772 for the 11 year of the rain of our Sovering Lord George the the third wrote by Zenas Phiney." The log continues with tight, crabbed entries, noting weather, latitude, sail handling and ships and people spoken and gammed with, until September 10. The log then jumps to the other end of the book and assumes a tabular form, with columns for time of day, speed, bearing, winds, position, and remarks - still kept by Phiney, and continuing without interruption from September 11. In this latter part the “Dolphin” is on the Grand Banks, then headed for Cape Cod. The log ends, "I have bene to sea from the 6 Day of May to the 4 Day of October which is 5 months except 2 Days and have not let my feet on land for the time." This is followed by a 23 page navigation lesson book, with instructions and diagrams in someone else's fine hand, written only on the rectos, and with Phiney's rough notes below and on the versos of many of the leaves. Then 6 pages of Phiney's notes on navigation, including rules for calculations employing the "Sons Dicklination." Then what looks to be an invented practice log of an "Intended Voige", and another of an "Entended Voige, each 2 pages in length.

In summary, what we have is the whaling voyage of the sloop "Dolphin" of Boston, in the summer of 1772, broken into two parts, separated by Zenas Phiney's navigational workbook and notes.

American whaling logs of this vintage are rare. Sherman cites only seventeen pre-1800 examples held in American institutions. Very few pre-Revolutionary American logs have ever been offered in the trade, and most of these have been in poor condition or incomplete. The log of the "Susanna", 1784, sold at Swann’s in the second Barbara Johnson sale for $18,000 in 1997. It was incomplete, sixteen pages in length. Swann claimed, “This log represents one of the earliest logs in existence and also one of the most complete of the early examples” This log predates that one by a dozen years and is equal in length and detail. Hand bound in canvas covers. $12,500 (Offered by Ten Pound Island Book Co.)

---

Note: The opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Association.

.jpg)